There is no more ideology in design, says Alessandro Mendini

Design magazines today have lost their critical edge and are little more than catalogues, according to Italian designer, theorist and editor Alessandro Mendini.

This is because there are no longer any coherent design movements to write about, said Mendini, who edited influential Italian titles Casabella, Modo and Domus in the 1970s and 1980s.

"Now there is no more ideology," he said. "All the world is very confused, all the world is very violent. There are too many different possibilities."

Each of the magazines he worked on was aligned with a distinct ideology, he said, giving the titles clarity and strength.

"If I would do a magazine now, it would be impossible," he told Dezeen. "The magazines on paper I think could now be good documents, but not in a critical way."

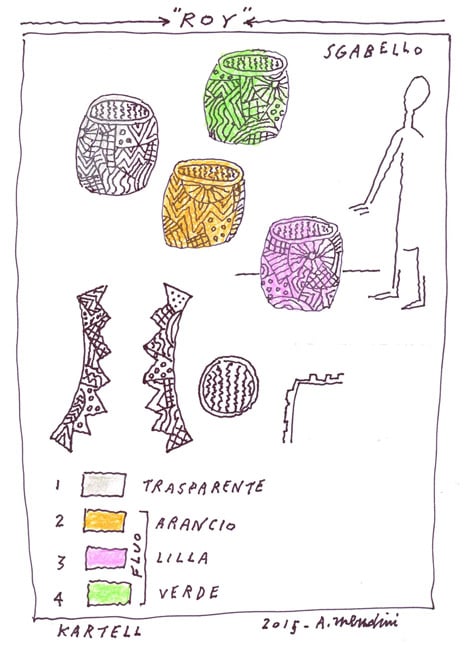

Mendini spoke to Dezeen at the Salone del Mobile in Milan in April, where he launched a plastic stool and clock for Italian brand Kartell.

The stool, called Ray, combines graphics derived from the work of pop artist Roy Lichtenstein with the form of a traditional Chinese stool.

The approach of combining form and pattern in this way is similar to the methodology Mendini used to design the 1978 Proust chair – one of the most iconic and revolutionary chairs of the last century.

"It's a very precise method of working," he said, explaining how the Proust chair combines a baroque form with a pattern of multicoloured paint blotches derived from the work of pointillist artist Paul Signac. "I connect shapes with the pattern of painters in a very methodic way."

The chair came about when Mendini set himself the task of designing a product for Marcel Proust, the French writer who is considered the father of the modern novel.

"It was an intellectual exercise, because this chair is very expensive, it has no function It's only for amusement," Mendini said. "But pointillism is a real theory. Because if each point is good, the whole object is good. Also in society: if each person is good, the society is good."

Born in 1931, Mendini is considered one of the most important living Italian designers and critical thinkers. He played a key role in the revitalisation of the country's design scene in the late 20th century.

He studied architecture at Milan Polytechnic and went on to be an influential figure in the radical design movement, as a member of experimental outfit Studio Alchimia, along with Ettore Sottsass.

With its penchant for surface decoration and bright colours and its rejection of strict modernist functionality, Studio Alchimia paved the way for the Memphis group - which Sottsass left Studio Alchimia to co-found - and the postmodern movement.

Mendini edited Casabella magazine from 1970 to 1976, when radical design was at its height. His tenure at Modo magazine between 1977 and 1981 coincided with the rise of interdisciplinary design, while his editorship at Domus from 1979 to 1985 gave impetus and critical rigour to the postmodern movement.

"The way of realising the magazines was very precise, because the design [ideology] was strong," he said.

Printed magazines still have a role to play today, he said, but this is more a role of cataloguing what is happening in the design world, rather than providing a critical framework.

"Then also there is the crisis of the paper, so for magazines printed on paper, it's a very bad time," said Mendini, who briefly returned to Domus as editor in 2010.

He added that although he feels digital media is important, he never uses it. "I write with a pencil," he said.

Below is a transcript of the interview with Mendini:

Marcus Fairs: Tell me about the two products you've designed for Kartell. I understand you've been friends with Kartell president Claudio Luti for a long time.

Alessandro Mendini: I was the editor of a magazine. The name of the magazine was Modo. The offices of Modo were inside the Kartell factory. So for five years I went there every day and I got to know all the people there. And I met the young Claudio Luti there. And then for 30 years we never met again.

Then some months ago we met in Florence because I won a prize, and he presented the prize. And he told me we should do something together. So I designed some objects, sketches. We talked about the sketches, he chose the stool and very, very quickly – too quickly! – we designed it.

Marcus Fairs: Why is it influenced by Roy Lichtenstein?

Alessandro Mendini: Because my way of working is to find a relationship with people that I like. So for example, I don't know if you know my Proust chair? It has a strong a relationship with Proust, with Pointillism. So I also like the work of Roy Lichtenstein. But I'm interested also in tradition.

For example the Proust Chair is a Baroque shape mixed with Pointillism. Two very different situations. The shape of this stool is Chinese; a Chinese ceramic stool. I mixed Lichtenstein and the Chinese stool together. It's a kind of serious play.

Marcus Fairs: Is there an intellectual relationship between Lichtenstein and the Chinese stool? Or is it just for fun?

Alessandro Mendini: For me it is not only fun, because it's a very precise method of working. I connect shapes with the pattern of painters in a very methodic way. It's a method.

Marcus Fairs: The Proust chair was revolutionary. Tell me the story of that chair.

Alessandro Mendini: Well. It was 1978 and I wanted to realise a very enigmatic object: not painting, not industrial design, not sculpture, but something very mixed. I'm really interested in transforming the objects in novels; it's a literary way of doing design. The objects are like personalities; all my objects are like characters. One is good, another one is bad. It's a kind of comedy and tragedy.

At that time my attention was to think what could happen if I made a chair for Mr Proust. I designed also a stool for Giotto and a table for van Gogh.

Marcus Fairs: Did you approach designing a chair for Proust as a serious, functional task? Or was it an intellectual exercise?

Alessandro Mendini: It was an intellectual exercise, because this chair is very expensive, it has no function. It's only for amusement. But Pointillism is a real theory. Because if each point is good, the whole object is good. Also in society: if each person is good, the society is good. And the Pointillism – I did a lot of work in mosaic. Because you can incorporate all the world in this small, square piece of glass.

Marcus Fairs: What would Proust say if you gave him the chair?

Alessandro Mendini: [Long pause] Proust did not have good taste in furniture.

Marcus Fairs: So would he like it? Or not?

Alessandro Mendini: Maybe he would like it! [Laughs]

Marcus Fairs: You spent a lot of time working on magazines. What is the role of the media in design today? We have digital media; websites like Dezeen. People are talking about the death of the critic and the rise of the short-attention span due to social media. What is the place of a magazine, of the media, in today's design world?

Alessandro Mendini: I can answer like this, because I worked for three magazines. The first one was Casabella, the second was Modo and the third was Domus. They corresponded to very precise ideologies: radical design at Casabella; interdisciplinary at Modo; and Postmodernism at Domus. The way of realising the magazines was very precise, because the design [ideology] was strong.

Now there is no more ideology. All the world is very confused, all the world is very violent. There are too many different possibilities. So if I would do a magazine now, it would be impossible. Then also there is the crisis of the paper, so for magazines printed on paper, it's a very bad time. The magazines on paper I think could now be good documents but not in a critical way.

Marcus Fairs: You mean like a catalogue?

Alessandro Mendini: Yes. Which is important too.

Marcus Fairs: What do you think about digital media?

Alessandro Mendini: I'm sure it is a very important thing but I don't use it at all. I write with a pencil.