Postmodern architecture: San Cataldo Cemetery by Aldo Rossi

Pomo summer: Aldo Rossi's unfinished San Cataldo Cemetery in Modena, Italy, is considered one of the first and most important Postmodern buildings. As part of our Postmodernism series we explore how the architect, who denied being part of the controversial movement, designed the seminal building in 1971 while recovering from a car crash (+ slideshow).

Rossi once declared that "I cannot be Postmodern, as I have never been Modern," yet his cemetery for Modena displays the strong colouring, bold form and historically referential detailing that became synonymous with the movement.

American architecture critic Charles Jencks, who defined the movement in his 1977 book The Language of Post-Modern Architecture, viewed Rossi as one of the leading Postmodernists and regarded the cemetery as the Italian architect's most important project.

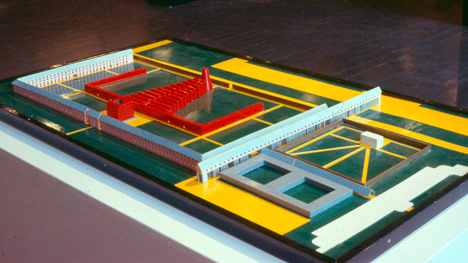

At the centre of Rossi's design is a cube-shaped ossuary for housing remains and a conical tower that marks a communal grave. Set within a courtyard on the outskirts of Modena, the ossuary is covered in terracotta-coloured render, while the perimeter buildings that enclose the courtyard feature steely blue roofs.

Rossi was born in Milan in 1931 and studied architecture at the city's polytechnic university, graduating in 1959. While he is better known for his built works, Rossi wrote for Italian architecture magazine Casabella throughout the later part of the 1950s and published texts on urban theory in the 1960s and 1990s.

He also branched into industrial design, creating household products with strong architectural forms including La Conica, the iconic stainless steel coffee maker he designed for Italian manufacturer Alessi in the 1980s.

The architect formulated his initial designs for the expansion of the cemetery with his colleague Gianni Braghieri. It was Rossi's first major public appointment and was to bring him fame outside Italy for the first time in his career, opening doors to projects in America, Japan and in other parts of Europe. He later became the first Italian recipient of the Pritzker Prize in 1990.

Rossi had actually set his sights on another project and had been working on his entry for the 1971 Centre George Pompidou competition, which was eventually won by Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano, but a serious car accident just weeks before the deadline hospitalised Rossi and scuppered his bid for the Parisian arts centre.

During his recuperation Rossi refocussed his attention on a competition for the expansion of the Neoclassic San Cataldo Cemetery in Modena. He hoped to put into practice the urban theories he had laid out in his 1966 text Architecture of the City, in which he stated that architecture should be embedded within the existing fabric of the city.

While Rossi had previously completed several Modernist-influenced projects in the 1960s including a housing scheme in Milan, the cemetery is his first project to reflect Postmodern aesthetics and values.

The design, which took place in two phases between 1971-6 and 1980-8, draws on the detailing of the adjacent Neoclassical cemetery in a way that Modernism would have rejected.

His appropriation of elements from this preceding architectural style coupled with the adoption of a muted blue and terracotta colour palette is distinctly Postmodern in its approach.

"The Cemetery of San Cataldo was a turning point in the life and work of Aldo Rossi," said Portuguese architect Diogo Lopes, author of the recently published Aldo Rossi monograph Melancholy and Architecture.

Diogo said that during his stay in hospital, Rossi started "coming to terms with the idea of his own death," and the experience caused him to re-evaluate his approach to architecture.

"Perhaps as a result of this incident, the project for the cemetery at Modena was born in the little hospital of Slawonski Brod, and simultaneously, my youth reached its end," wrote Rossi, who was driving to Istanbul when he had the accident and recuperated in the small town in Yugoslavia (now Croatia).

"I lay in a small ground-floor room near a window through which I looked at the sky and a little garden. Lying nearly immobile, I thought of the past, but sometimes I did not think: I merely gazed at the trees and the sky."

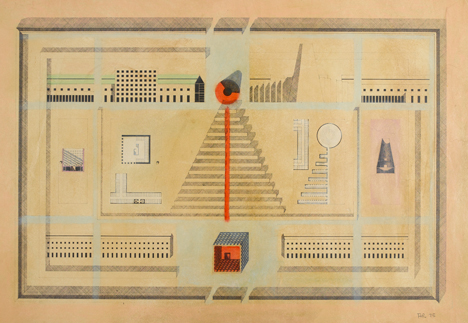

Rossi's development drawings for the cemetery show triangular, square and circular structures that resemble children's building blocks. The forms reminded Rossi of Gioco dell'Ocha (Game of the Goose), a popular children's board game in Italy where players move along a spiralling route, encountering obstacles such as a bridge, well, maze, and ultimately, death.

The elements of the game can be interpreted in Rossi's lurid-coloured plans for the cemetery in the metal staircases that ascend and descend the walls of the ossuary cube, the partially built colonnades that enclose the graveyard, and a cone-shaped tower in the centre as the final square, a communal grave.

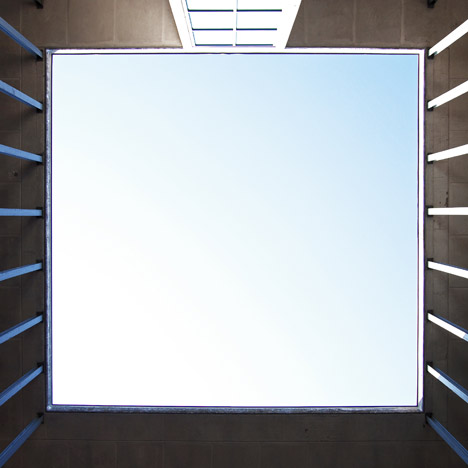

Rows of identically sized windows and doorways puncture the orange facade of the ossuary that is the centrepiece of the cemetery grounds. Rossi conceived this skeletal structure, which has no window panes, doors or roof, as a city for the dead.

A concrete grid of funerary niches covers the interior walls and is accessed via a network of metal staircases. The regimented openings replicate the detailing of the cemetery's enclosing walls, a feature that in turn acknowledges the layout of the adjacent cemetery, which features tall arched colonnades and warm-toned render. In many ways, Rossi's extension with its column-lined walkways and enclosed graveyard is a reduced form of this original design.

The earthy toned facade of the ossuary and steely blue roofs of the perimeter buildings are a clear break away from the stark grey concrete favoured by Modernists in the preceding decades.

"It was also the first project where he used colour extensively with the sky-blue sheeting of the roofs, the pale rose of the stucco of the walls of the tombs, and the dark red of the cubic ossuary," Lopes told Dezeen. "This could be seen as an early sign of a feature commonly associated with Postmodernism."

Rossi's designs for the Modena competition were widely published, making the cover of Casabella magazine in 1972.

Around the same time another seminal event in architecture history took place: the Pruitt Igoe housing development in Missouri, designed by World Trade Center architect Minoru Yamasaki in the early 1950s, was demolished.

Charles Jencks identified the dynamiting of the 33-building complex as marking the death of Modernism.

"Modern Architecture died in St Louis, Missouri on July 15, 1972 at 3.32pm (or thereabouts) when the infamous Pruitt Igoe scheme, or rather several of its slab blocks, were given the final coup de grace by dynamite," wrote Jencks in The Language of Post-Modern Architecture.

Looking around for a new movement to replace Modernism, Jencks was drawn to the the work of Robert Venturi, Hans Hollein and Charles Moore – and Rossi, whose drawings for Modena perfectly fitted the new Postmodern approach he had identified.

When Rossi was awarded the Pritzer Prize in 1990, the jury said: "Rossi has been able to follow the lessons of classical architecture without copying them; his buildings carry echoes from the past in their use of forms that have a universal, haunting quality."

"His work is at once bold and ordinary, original without being novel, refreshingly simple in appearance but extremely complex in content and meaning," they added. "In a period of diverse styles and influences, Aldo Rossi has eschewed the fashionable and popular to create an architecture singularly his own."

Rossi died in 1997 following a second, fatal car crash near his home in Milan. Today his most important project stands partially occupied but incomplete, missing its conical chimney-like tower and a branch of its covered walkway.