Key Projects by Wang Shu

Here’s a selection of projects by Chinese architect Wang Shu of Amateur Architecture Studio, who has been named 2012 Pritzker Prize Laureate (see our earlier story).

Top and above: Ceramic House, 2003-2006, Jinhua, China

The award will be presented at a ceremony in Beijing on 25 May.

Above: Ceramic House, 2003-2006, Jinhua, China

Read more about the Pritzker Prize on Dezeen here.

Above: Ningbo History Museum, 2003-2008, Ningbo, China

Photography is by Lv Hengzhong, apart from where otherwise stated.

Above: Ningbo History Museum, 2003-2008, Ningbo, China

The biography below and image captions are from the prize organisers:

Wang Shu, who makes his home and works in Hangzhou, was born on November 4, 1963 in Urumqi, a city in the western most province of The People’s Republic of China, Xinjiang. His father is a musician as well as an amateur carpenter. His mother, whose home is Beijing, is a teacher for young children as well as the school librarian. His sister has followed in their mother’s footsteps and become a teacher.

Above: Ningbo History Museum, 2003-2008, Ningbo, China

His parents’ pursuits sparked an interest in Wang Shu for materials, crafts and literature. When he was a teenager, he had to travel between Urumqi and Beijing by train, a distance of 4000 km, four days and four nights train ride. These travels afforded him the opportunity to grow up with a broad and changeable nature. Without any teacher of art, he began to draw and paint on his own. Those early interests at first seemed to be leading him toward a career as an artist or writer.

Above: Ningbo History Museum, 2003-2008, Ningbo, China

Many of his drawings were left on the walls of the narrow street adjacent to the courtyard of the home where he once lived in Beijing. Even many years after he moved away, his neighbors protected the drawings on the walls, waiting for his return. However, Wang Shu chose to live and work in Hangzhou. It was because of the city’s famous natural landscapes, and for its long tradition of water and hill landscape painters.

Above: Ningbo Tengtou Pavilion Shanghai Expo, Shanghai, China, 2010

Photograph is by Fu Xing

His parents pointed out that it would be extremely difficult to earn a living in either of those fields and pushed to have him study science and engineering.

He compromised in that he would study in an arts related scientific-engineering field, i.e. architecture. He freely admits that when his teachers learned of his plans, he says, “They thought I must be crazy, but so few ordinary Chinese people really know anything about the study of architecture.” After several months of study in the field, Wang Shu knew that this was the profession he wanted to learn.

Above: Ningbo Tengtou Pavilion Shanghai Expo, Shanghai, China, 2010

Photograph is by Lu Wenyu

When he first graduated from the Nanjing Institute of Technology, Department of Architecture, he went to work for the Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts in Hangzhou doing research on the environment and architecture in relation to the renovation of old buildings. Nearly a year later, he was at work on his first architectural commission, the design of a 3600 square meter Youth Center for the small town of Haining (near Hangzhou). It was completed in 1990.

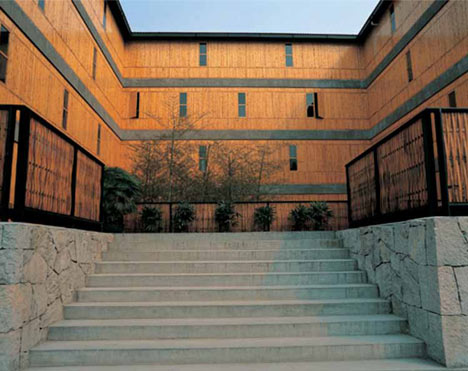

Above: Xiangshan Campus, China Academy of Art, Phase I, 2002-2004, Hangzhou, China

Photograph is by Lu Wenyu

From 1990 to 1998, he had no commissions, and he preferred not to take a government or academic position. Instead, he went to work with craftsmen to gain experience in actual building. Every day, from eight in the morning until midnight, he worked and ate with the craftsmen, considered by many to be the lowest level of their society, but he learned everything he could about construction practices. The projects he did at that time were all renovation projects of old buildings, and because old buildings were deconstructed during the fast development of cities, these small works of his were also demolished.

Above: Xiangshan Campus, China Academy of Art, Phase I, 2002-2004, Hangzhou, China

Photograph is by Lu Wenyu

When he was a student at university in the 1980s, he also began study the art history of not only Chinese Europe, but of India, Africa and America, and gradually expanding his field of study to not only historic art, but also contemporary art, philosophy, literature, anthropology and the movies. During 1990 to 1998, he had the time to continue his researches in these fields to study and think further. In Wang Shu’s words, “I believe in starting with a broad vision and condensing it to fit the local situation.”

Above: Xiangshan Campus, China Academy of Art, Phase I, 2002-2004, Hangzhou, China

Photograph is by Lu Wenyu

It was in 1997 that he and his wife Lu Wenyu, who is also an architect, founded their “Amateur Architecture Studio,” which has grown into a ten-person office, and has become a fairly famous name in China. The name is a partial response to their critique of the architecture profession in China which they view as complicit in the demolition of entire urban areas and excessive building in rural areas. He says, “I can’t do this, we must not demolish history in order to develop.”

Above: Xiangshan Campus, China Academy of Art, Phase II, 2004-2007, Hangzhou, China

Rather typical of his thought and work processes is the Ningbo Historic Museum, a commission that he won as a result of an international competition in 2004. He often explains that part of the motivation behind his design is to remind people what life was like in the past in the harbor city of Ningbo. By collecting recycled building materials from the area to be used in the construction of the museum he was seeking to make a building that could be a small city in its own right and bring up memories of the past.

Above: Xiangshan Campus, China Academy of Art, Phase II, 2004-2007, Hangzhou, China

He explains further his work procedure as three distinct stages. The first is to convince the government and the client. Second, he deals with the design details in relation to construction issues. And third, he describes as, “the hardest of all, because the Chinese often think of a building as just a container whose functions can change at will, I can have no influence on this third stage.”

Above: Xiangshan Campus, China Academy of Art, Phase II, 2004-2007, Hangzhou, China

An example of this is what started out as a Contemporary Art Museum in Ningbo, but would end up a little bit different. “When we presented our plan,” Wang Shu explains, “the government said they had money to build, but not to operate the structure. They needed space to rent out to generate funds. I told them, that apart from selling fish, they could do whatever they wanted on the ground floor, but art should be on the first floor.”

Above: Ningbo Contemporary Art Museum 2001-2005, Ningbo, China

He explains his design process as very similar to the traditional Chinese painter. First, he studies the cities, the valleys and the mountains. Then he thinks about these things for about a week, not drawing at all. Then, as was the case with the Ningbo Historic Museum, one night when he could not sleep, the design materialized in his mind. He immediately took pencil to paper and drew everything, including numbers, structure, sizes of spaces, locations of entrances, and other functions. “Then,” he says, “I drank tea.”

Above: Ningbo Contemporary Art Museum 2001-2005, Ningbo, China

The whole process is one of thinking, drawing, and discussing. Step by step, a more defined project evolves, and then assistants from his office participate creating further plans and drawings using the computer. A next step involves a discussion about details and materials.

He described another situation when he had to design three museums in different places at the same time, “My wife, Lu Wenyu, and I are the only partners in the studio. The rest are all our students. I sent them all home for a month so I could work on these three museums. But they were not on vacation. They all had homework assignments: books on French philosophy, or Chinese paintings, movies, or whatever might be helpful. When we all got back together,” he says, “we had discussions before we began work again.” His role of teacher extends beyond his studio. In 2000, he became a professor at the China Academy of Art in Hangzhou. In 2003, he was named head of the Architecture Department there, and in 2007, he was made the Dean of the Architecture School.

Above: Library of Wenzheng College, 1999-2000, Suzhou University Suzhou, China

Photograph is by Lu Wenyu

Wang Shu has explained in lectures and interviews with journalists, repeating many times, that “to me architecture is spontaneous for the simple reason that architecture is a matter of everyday life. When I say that I build a ‘house’ instead of a ‘building’, I am thinking of something that is closer to life, everyday life. When I named my studio ‘Amateur Architecture’, it was to emphasize the spontaneous and experimented aspects of my work, as opposed to being ‘official and monumental’. My work is more thoughtful than simply ‘built’.”

By naming his practice “Amateur Architecture Studio,” Wang explains that the implication should be that the “handicraft aspect” of his work is more important to him that what he considers much of the “professionalized, soulless architecture as practiced today.” At an architecture conference in Beijing in the 1980s, he created controversy when he stated that there was no architecture in China. He defined an architect in China then as simply someone who knew how to draw, and could be drawing all days, but not necessarily thinking about what he was drawing. He feels that the situation today has changed, but there is still too much influence of money and business.

Above: ceiling of gallery, Five Scattered Houses, Ningbo, China, 2003-2006

Photograph is by Lu Wenyu

With further elaboration, Wang Shu says, “The Amateur Architecture Studio is a purely personal architecture studio. It should not be even referred to as an architect’s office because design is an amateur activity and life is more important than design. Our work is constantly refreshed by various spontaneous things that occur. And, most important, we encourage independence and individualism to guarantee the experimental work of the studio.”

Wang also speaks of the temporary character of his firm’s work “My belief is that architecture should work hand-in-hand with time. Sometimes I prefer to use less costly materials that can be replaced when damaged. And I associated buildings and plants – when they come together, as long as time keeps going, architecture is subject to constant changes. Temporary as I use the word is not meant to mean disposable.”

Above: roof top cafe, Five Scattered Houses, Ningbo, China, 2003-2006

Photograph is by Lu Wenyu

He has often commented that he sees himself as a scholar, craftsman and architect, in that order. This is reflected in the design process of his work. A project is open to change, adapting constantly in response to the environment and conditions, even conditions that may arise during the building phase of a project. Amateur Architecture Studio’s work is often characterized by spontaneous changes throughout the process of design and construction.

Vertical Courtyard Apartments, 2002-2007, Hangzhou, China

Photograph is by Lu Wenyu

He explains further, “A hundred years ago in China, the people who built houses were artisans; there was no theoretical foundation for architecture. Today, an official architectural system has been established, but I chose handicrafts and the amateur spirit over the system. For myself, being an artisan or an amateur is almost the same thing.” His interpretation of the word is relatively close to one of the unabridged dictionary’s definitions: “a person who engages in a study, sport or other activity for pleasure rather than for financial benefit or professional reasons”. Although in Wang Shu’s interpretation, the word “pleasure” might well be replaced by “love of the work”.

Vertical Courtyard Apartments, 2002-2007, Hangzhou, China

Photograph is by Lu Wenyu

He compares this concept to creating a Chinese Garden, which he says really cannot be designed. “Many unforeseeable things happened here in China all the time so you have to improvise,” explains, “it is better to be able to solve problems at the moment they arise.” He emphasized that the need to be flexible when building is typical in China.

“I design a house instead of a building,” says Wang Shu. “One problem of professional architecture is that it thinks too much of a building. A house, which is close to our simple and trivial life, is more fundamental than architecture.” He often expresses that for him, humanity is more important than architecture, while simple handcraft is more important than technology. Thus the name of his office, “Amateur Architecture” and his approach reveals an experimental and critical attitude toward the building process.

Above: Decay of the Dome Exhibit 12th International Architecture Exhibit, Venice, Italy, 2010 - a test in Hangzhou

Photograph is by Lu Wenyu

As for early Chinese influences, he considers Tong Jun, a Chinese architect whose research into the Jiangna Gardens of Suzhou, the main one. Wang Shu’s passion for calligraphy has prompted at least one journalist to write that sometimes his designs reflect the freedom of brushstrokes and the tension between Chinese calligraphic characters. From the international community, he lists Aldo Rossi, Alvaro Siza (both also Pritzker Laureates), Le Corbusier,Mies van der Rohe,Louis Kahn, Carlo Scarpa, and some of Tadao Ando’s (another Pritzker Laureate) early work.

Above: Decay of the Dome Exhibit 12th International Architecture Exhibit, Venice, Italy, 2010 - installation in Venice

Photograph is by Lu Wenyu

Not surprisingly, Wang Shu serves as Dean of the Architecture School in China Academy in Hangzhou as well as having designed some 21 buildings spread over some 130 acres near Xiangshan, and now teaches in the school as well. One of his most important commissions, it was accomplished in two three-year phases.

In 2009, his solo exhibition, “Architecture as a Resistance” was shown at the BOZAR Art Center in Brussels, Belgium. He is a frequent guest lecturer at colleges and universities around the world, and is often invited to speak at international conference and institutions.