Architecture magazines are ruining architecture, Brooklyn-based artist and architect Vito Acconci told Dezeen at Vienna Design Week, stating that "architecture is the opposite of an image".

Acconci believes the only difference between a piece of architecture and an image is that people can move through architecture, meaning the element of time is the crucial difference. "Architecture is not about space but about time," he says.

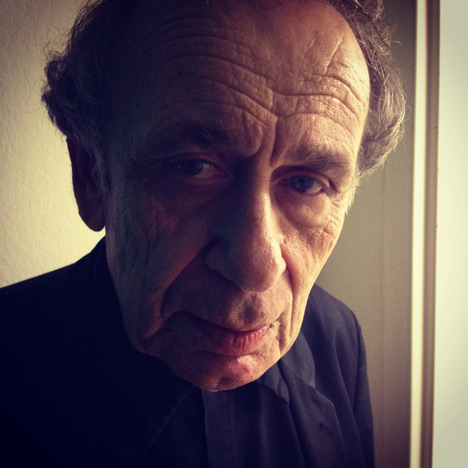

Speaking to Dezeen editor-in-chief Marcus Fairs in Vienna earlier this month, the 72-year-old described how he started out as a poet in the 1960s, becoming fascinated with the way the reader uses words to navigate across the page. Later he worked as a performance artist and now runs Acconci Studio, which focuses on landscape design and architecture.

Acconci explains how he now regrets his notorious 1971 "Seedbed" performance - which saw him lie hidden beneath a ramp in the Sonnabend Gallery in New York, verbally fantasising about, and masturbating over, gallery visitors passing over him – explaining that it "ruined my career".

Below is a transcript of the conversation, which took place in Vienna during Vienna Design Week, where Acconci chaired the jury of the inaugural NWW Design Award along with Fairs and Italian designer Fabio Novembre, who also took part in the discussion.

Marcus Fairs: So, first of all Vito, tell us a little bit about yourself – give us the quick resume of your career.

Vito Acconci: I started as a writer, in the mid- to late- 60s. I was writing poetry. I wasn't the only one who wanted things like this, but I wanted words to be closer to fact, I wanted words to almost try to be physical, you know? When you see words, you're used to looking through words to subject matter. I hoped that the words could have some concrete specificity of their own. So you know, when I wrote, when I started a poem, I started by saying: how do I move? How do I move from left margin of the page to right margin? How do I move from one page, next page etc? After writing poetry 'til maybe towards the end of the 60s I started to think: why am I moving across the page? I should be moving across actual space, physical space.

So work changed context. No longer a poetry context, but an art context, because at that time art was being turned upside-down. It wasn't necessarily painting and sculpture anymore, notions of performance were being talked about. And it had to do with the time, it was a time of very long songs in pop music. Neil Young, Van Morrison, not the traditional three-minute song, but seven-minute song, nine-minute song. And it was a time when - and I can't say everybody was thinking about this - but people were thinking about "finding themselves". How do you find yourself? So in a context like that, I thought: what else can I do but do work that had something to do with me, turning on myself, going through some enactment of what finding oneself can be? But that was maybe a starting point, and eventually it was about: how do I face you? How do I face you, the viewer?

But gradually time changed. "Self" wasn't that important anymore. It was important at the end of the 60s, by '72, '73 it probably wasn't an issue anymore. So a lot of us who were doing performances were starting to do something called "installations". And art terms were never, almost never, formed by the people who did them, who did the so-called art. The words were given by curators, by critics. So the word “installations” was used, I mean art has used an amazing number of very vague words. "Installation" might be the vaguest.

Mur Island, Graz, 2003

Marcus Fairs: Tell us about what the studio does now, how do you place yourselves in terms of space-making, helping people move through space?

Vito Acconci: When the studio formed, at the end of the 80s, I thought: I wanted to form a studio of people because I wanted to do architecture, yet I thought: I can't possibly do it alone, because I don't really know architecture. Though stuff throughout the 80s was architecturally oriented.

But I thought it was important to form a studio of people who were a group of people, because I thought: I'm interested in public space. But I don't know if public place should come from a single person, come from a private person. I thought the best way to get in notions of public place, is to have conversations. So the reason to form the studio was, I could work with people who knew more about architecture than I did, but everybody knows architecture, because there's nobody who doesn't walk through architecture. So architecture is the one thing that probably everybody knows, though probably people wouldn't admit that because they don't realise going through a building is starting to know architecture.

We built a very small percentage of our projects, possibly 10%. We're asked to do a number of projects... but the projects we're asked to do are probably more specifically so called 'public art projects' rather than "real architecture projects". We try to turn them into architecture, which means every project we do has people using the space. What we don't want at all, is a space that's looked at from outside. It has to be a traversed space. We hope we can do some projects that turn the space a little bit upside-down. That turn the space a little bit inside out, so that, you know the hope is that if people go through spaces like this, they say: wow, you know? If we can go through a space like this, maybe we can change our own space. Do I know if anybody says that? Of course not. Ideally we want every space to move. Because I think now people are always subjected to their space, and until people can start to make some change in the space they're in, only then, I think, can people start to be free with architecture. Can that ever happen? I don't know.

Marcus Fairs: We were together yesterday, judging a design prize, and my personal perception was of a lot of the work we were seeing was that these young people, they're living in an amazing time, and they're not really being particularly adventurous creatively.

Vito Acconci: No, they're not. They're not because it's a tough money time.

Marcus Fairs: To compare when you were growing up, when you were a student, when you were starting to practice the freedoms that you had, the kind of provocations that you were able to get away with, and…

Vito Acconci: I don't think my generation thought of money that much. There were people who were making an amazing amount of money, there were a lot of painters in my generation, but I think a lot of my generation thought that because of the kind of work that we were doing, we were going to destroy the gallery system. We were totally naive. We made the gallery system probably stronger than ever, because galleries could say: look what we're showing. You can't buy this. But, we can take you into the back room and sell you a Jasper Johns, and sell you a Robert Rauschenberg. But you know again, ten or fifteen years before that, they were probably the decoys to get people in the galleries. Yeah, I think it's a very different time, but I still think there are ways to do what maybe is more necessary to do.

Marcus Fairs: What's happening, do you think, that is exciting? What's happening in the creative sphere? And maybe it's not architecture, maybe it's not design. What out there excites you?

Vito Acconci: I think there's some interesting architecture, it's not necessarily built, I don't know who are the interesting architects. I know the way we're thinking is: I wish we could do architecture that wasn't made of planes, that wasn't made of surfaces. I wish we could do an architecture of pixels and particles, I wish we could do an architecture of thick air. We don't know how to do that. But I think enough people are thinking somewhat along those lines, that if people keep on wanting to do something, maybe somebody does it.

Fence on the Loose, Toronto, 2012

Marcus Fairs: Do you think that there's a radicalism, or a naivety that's missing today. I mean I was reading about your “Seedbed” project. I mean things today that young designers or artists might see as provocative and radical don't really come close to that, do they? Can you tell us a little bit about that project?

Vito Acconci: You know [laughs] I mean I wish I hadn't, kind of wish I hadn't done it. But it kind of ruined my career.

Marcus Fairs: Did it really?

Vito Acconci: Of course it did. I'm the person who did Seedbed, and I can never get past that. No one will ever take me seriously, as something like an architect, or designer, because of that. When probably very few people saw it at the time [laughs].

Marcus Fairs: But everybody's probably heard about it. But you say you've ruined your career - is that a regret? Or would you be somewhere else right now if that hadn't happened?

Vito Acconci: I don't know! You know that was in 1972, I wish people would take more seriously what we do in 2012, or 2006, or you know. It labelled something, even though you know, I did performance for three years. I started doing performance in 69, the last performance I did was in 1973. I never thought of something I did as a final point, I always thought that this could lead to something else. I wanted to get excited by what we did, and not fall into something we had done before. Those pieces made sense at that '69 to '72 time, they don't make sense any more.

Marcus Fairs: If it's not too painful for you, just briefly tell us what Seedbed was all about.

Vito Acconci: It was at a gallery show. The room for Seedbed was a room about 20 feet wide, 45 feet long, halfway across the floor, the floor rises to become a ramp that goes up to a height of about two-and-a-half feet, three feet at the far wall. Let me give you some reasons for this though, because I know you want just the ridiculous shock value of it.

Marcus Fairs: [Laughs]

Vito Acconci: But I didn't see it that way, and the reason I did it was that I hated the fact that everybody who knew a project of mine knew what I looked like, and I started to think: am I developing a personality cult? Or am I trying to do something else? I hoped I was doing something else. So therefore I wanted to find a way where I wouldn't be seen from opening time at the gallery, to closing time. This all happens before and after people leave, I'm underneath the ramp. So I'm underneath the ramp for an eight hour gallery day. I'm underneath people walking, so I hear people's footsteps.

I try to build sexual fantasies on those footsteps. People hear my voice saying things like: I'm doing this with the person on my left, I'm touching your hair, I'm running my hand down your back, etc etc etc. So every once in a while, or sometimes more, sometimes fewer times, I masturbate. People probably hear me. So the aim was to, can I make some connection with people above this floor?

I mean the masturbation was, I didn't even think about the masturbation 'til a few days before the project. I knew that I wanted to be under there, I didn't know what I wanted to do. And you know, because of my background in words, I found out what I should do by means of words. I used Roget's Thesaurus, that's an important book to me, because it's about analogues of words. It's not about definitions, it's very different than a dictionary, but you get almost an atmosphere of words. So I looked up the word 'floor', and came upon words like 'undercurrent', etcetera, came upon the word 'seedbed', and thought: well, now I guess I know what I have to do. But you know, it didn't start as that, but it started as I want to do something that possibly implicates a viewer, but I had no idea, because all I could hear were footsteps.

Wave-A-Wall, New York, 2006

Marcus Fairs: Talk about some of the architecture you've done. The Island in the Mur project in Graz [in Austria] for example. So describe that project.

Vito Acconci: Yeah, it was done when Graz was the European Cultural Capital of the year, in 2003. And we were asked to do, to use the River Mur that runs through Graz, as a place for what the people in Graz called a 'person-made island'. And they wanted this island to have three parts: a theatre, a cafe, and a playground. So when we started, we started playing around with ideas like, can we make an island of water? We didn't quite know how to do that, so we started to focus on function. We said, let's start with the theatre, a somewhat conventional shape for a theatre, is a bowl. What if we twist the bowl? Now the bowl is a dome. The bowl is a theatre, the dome becomes a bar and cafe, and a twisting space from one to the other becomes the children's playground. Which I don't know if I left this out, I think I said that Graz wanted us to do a dome?

I mean that's the basic project and what we did, was, it gave us a chance to do an indoor space for the cafe, it gave us a chance to do a kind of playground that was a part of this shifting space from bowl to dome, and vice versa.

And sometimes I regret this, but it's probably the project that's closest to architecture. The people who work with me have gone to architecture school, they all want to think we're doing architecture. We're doing something like architecture, but usually architecture doesn't have a million dollar budget, it has bigger budgets than that. Though the Graz project was at that time six million euros, which at the time was probably nine million dollars. Certainly the most expensive… and not that I wanted, that I want to think that every project we do needs a lot of money to do it, but the problem is if it doesn't, if you want something to be used by people, if you can't spend money on it, it'll probably be gone in three weeks.

Marcus Fairs: So poetry, to art, to performance or installations, architecture, public space. Do you see the studio could shift still further?

Vito Acconci: Probably, into vehicles, maybe? I think future architecture is inevitably mobile.

Fabio Novembre: What do you think about Anish Kapoor as an architect?

Vito Acconci: Anish Kapoor as an architect?

Fabio Novembre: 'Cause he's turning more as an architect than as an artist, right?

Vito Acconci: Lately, yeah…

Fabio Novembre: He's experimenting with the space in a very interesting way, right?

Vito Acconci: Yeah, yeah, I mean I think that that Chicago space is pretty good. His London Olympics project…

Marcus Fairs: Oh my God, people hated that.

Vito Acconci: They hated it?

Marcus Fairs: They hated the aesthetic experience of looking at the tower. I mean, it's the least popular landmark in London.

Vito Acconci: Yeah, yeah I kind of came upon reports of that. I mean could they use it? [laughs]

Marcus Fairs: Yeah, yeah, you can travel up. You travel up to the top.

Vito Acconci: And does anything happen when you get up to the top?

Marcus Fairs: You look out the window.

Vito Acconci: You go down [laughs]. You go up in order to go down.

Fabio Novembre: What is your personal opinion on the sensibility of the space that Anish Kapoor is developing?

Vito Acconci: It's a little too grand for me. Not all the time, I think, but like that piece, that project particularly - but again, I wasn't there. I only could see it from photographs, it didn't seem like it made any possible change in people, they're just walking, and then they're walking down, so…

Fabio Novembre: What about Richard Serra? Cause Richard Serra basically is an architect. He cuts space, you know?

Vito Acconci: But he hates architecture.

Fabio Novembre: Yeah but he's doing architecture!

Vito Acconci: He doesn't think he does, but you know, I once probably made a big mistake, and I think it was in Frieze magazine, I don't remember now, when the interviewer asked me about Richard Serra, and I said: I'd like it so much more if when you got inside a Torqued Ellipse, there would be a hot dog stand inside. So that there'd be something for you to do [laughs]. If Richard Serra read that, he'd probably, he's probably out to get me [laughs] you know? Because he sees it as: no, you have to have no use but the appreciation of, you know. And of course, he can think that, but I don't know if space is as important as time, because yes, architecture may take up space, but it takes time to go through. To me, what taught me about architecture was a movie I saw at the age of 21 years old...

Fabio Novembre: Which was?

Vito Acconci: Alain Robbe-Grillet and Alain Renais' “Last Year at Marienbad”, which to me, it somehow foresaw, I didn't foresee it, but it somehow foresaw everything I was going to do. But I didn't know it yet. 'Cause I started to do a lot of things with sound, but this was much, much, much later. When I did installations, they all had sound, but you know, that was 1976, 1977. The movie has a narrator's voice, but particularly, the movie begins with a camera going down the corridor of what the narrator is calling this 'Baroque Hotel', and I think, without - I don't think I realised it when I saw it, but I realised: architecture can't be looked at from the outside; architecture is going through a space. Architecture is not about space but about time. And unless you travel through it, it could be a picture in an architecture magazine. And of course, most of my information about architecture comes from architecture magazines, but it kind of ruins architecture [laughs] It makes architecture an image. Architecture is the opposite of an image.

Marcus Fairs: I think that's really interesting: one of the things that internet publishing can do, is you can introduce the dimension of time, through movies, and stuff like that. But it's astonishing how reluctant architects have been to allow the public to experience their buildings on a time basis, they're still using a hundred-year-old technology to represent buildings.

Vito Acconci: Yes, yeah, yeah. I think unfortunately a lot of architects, I think, have a kind of 'master builder' complex [laughs] And they don't want people to change the space. I mean I've been with architect friends, who are taking me to a new building, a new house in San Francisco, and as we went in, he says 'Ah, I wish I had taken you here before they put the furniture in!' [laughs].

Marcus Fairs: Before they put the people in as well.

Vito Acconci: Yeah, yeah. I mean…yes and sure, I mean sometimes I've felt people do things that you might not want them to do, yet at the same time, I think you have to leave it to people after a while. You have your chance for a while, and then maybe the people will move out, and you can renovate it later [laughs]. I love the idea of "peopled space". I mean that's what makes architecture. It's gotta be at the behest of people. I think people should be able to say: why can't we change this wall? Why can't we make this wall moveable?