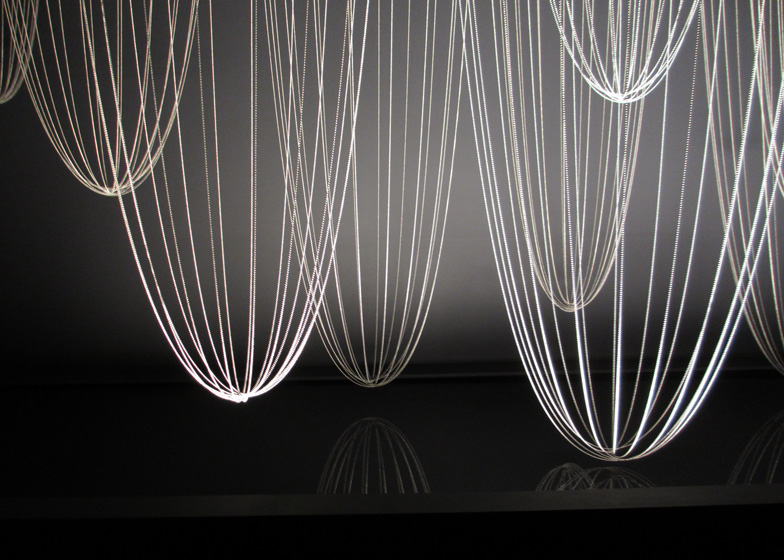

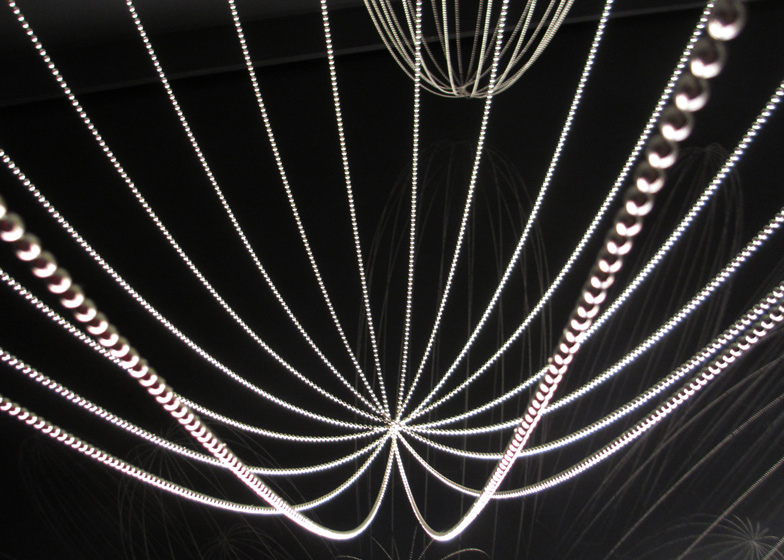

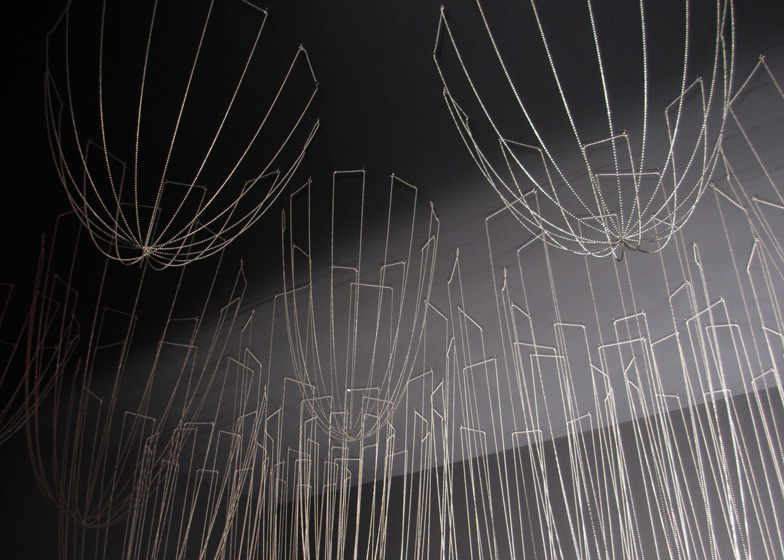

Design Miami: inspired by Gaudí's ingenious method to create the perfect curve, Anglo-Dutch design duo Glithero have hung loops of beaded chain over a shallow pool of water in an installation for champagne house Perrier-Jouët (+ slideshow).

Founded by British designer Tim Simpson and Dutch designer Sarah van Gameren, London-based studio Glithero was asked by Perrier-Jouët to come up with a piece to reflect the champagne house's art nouveau history.

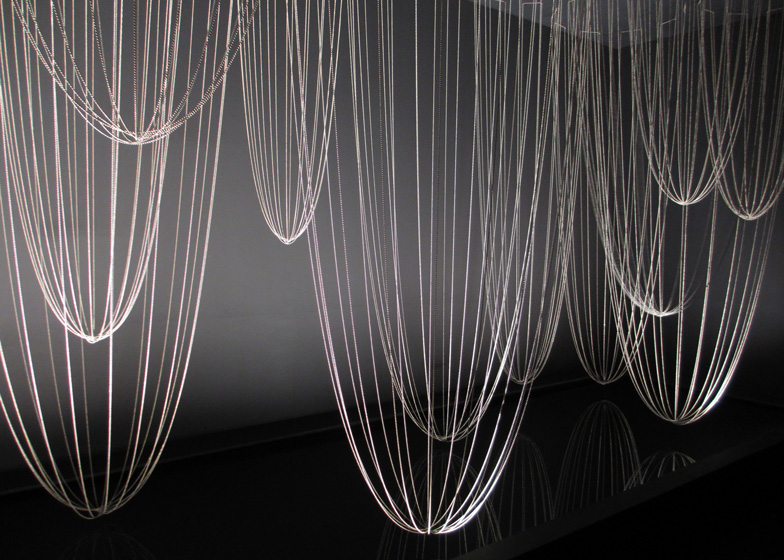

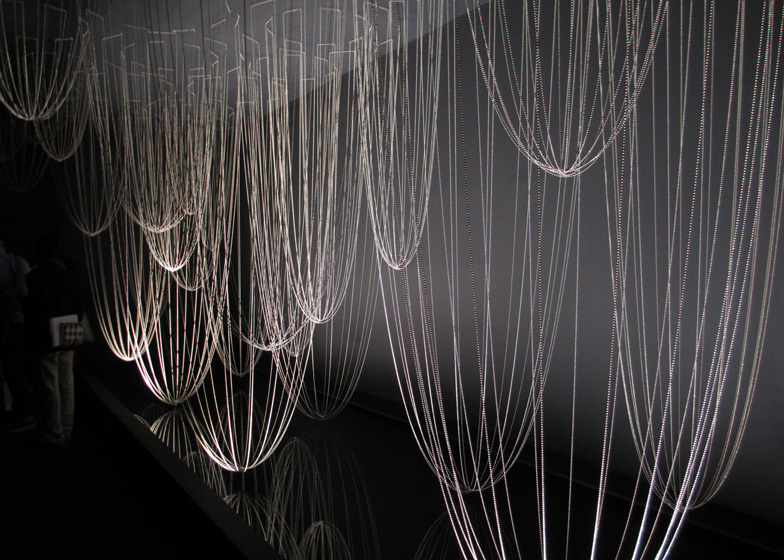

Lost Time is installed in a darkened room inside the Design Miami fair, stretching along a narrow corridor with a pool of water right beneath it.

The elongated domes are reflected in the water below, hinting at the bubbles of a champagne glass.

"We knew the affinity of Perrier-Jouët with art nouveau," said van Gameren, explaining that they made the link with Gaudí's architectural model for the art nouveau-influenced Sagrada Familia cathedral in Barcelona.

"It was an upside-down model, and it was completely made of strings and little bags of sand to keep the string nicely poised," continued van Gameren. "He mirrored it with a mirror underneath and used it as the basis for the structural fundaments of the Sagrada Familia.

"That's a really interesting thing – it's also almost like a tool that creates curves, and in this time, in this day and age, you probably have a computer to fill this function. What's really charming of course, is that he managed to do it so analogue," she added.

The designers also wanted to recreate the environment of the cellars in Epernay, France, where the champagne is made. "There is a really strange atmosphere in there because it's a bit humid, moist, and the walls are all chalky because that's where the grapes grow and all the bottles are stored there," van Gameren explained to Dezeen at the opening of the installation.

"We wanted to almost capture the timelessness that we had the impression there was in these vaults, or in these caves, and the reflections – because there were puddles on the floor and they reflected the ceiling, and spiderwebs with little dew drops. And it was almost like we wanted to take a little bottle and bring it here in Miami," she added.

The designers met and studied at the Royal College of Art in London and are also presenting photosensitive vases marked by strips of seaweed at Design Miami.

Other work by Glithero we've featured on Dezeen includes vases and tiles decorated with plants and a pair of self-supporting candles.

See more projects by Glithero »

See all our coverage of Design Miami »

Read the full interview below:

Emilie Chalcraft: How were you first asked to do this project and and how did you feel about working with a champagne house?

Tim Simpson: We were asked to participate with with Perrier-Jouët, and it began with a visit to Epernay to see how the champagne is made, which is exactly up our street because we're so at home on factory floors and seeing processes and especially when they are as authentic as making champagne. So that's how these things begin – you have to learn a lot about each other, and we learnt a lot about the heritage of their brand and how it's made, and the environment. For us the most interesting part of that process was seeing the fermenting. Because it's something that's really a labour; it's very slow.

Sarah van Gameren: It started in the summer more or less. One of the things we did was that we went to Epernay to go and visit the cellars. And there is a really strange atmosphere in there because it's a bit humid, like, moist, and the walls are all chalky because that's where the grapes grow on, and all the bottles are stored there. Every day they have to be flipped, because fermentation needs to sink to the other side.

And us being very interested in process, we find that kind of stuff a very interesting way to approach the brief, or, there was no brief, but the idea or the project. And we wanted to almost capture the timelessness that we had the impression there was in these vaults, or in those caves, and the reflection, because there were puddles on the floor and they reflected the ceiling. Spider webs with little dew drops. And it was almost like we wanted to take a little bottle and bring it here in Miami.

Because it's an interesting atmosphere – it also gives you the feeling that time stood still, and this reflection that happens in nature - you know, the symmetry of an object hanging above and then being exactly reflected opposite - this, I think, very pensive moment makes you think or stand still and realise something, and yeah, these elements we wanted to really bring.

And part of that was also that we knew the affinity of Perrier-Jouët with art nouveau, and we knew one very interesting [element] in art nouveau was the model [by] Gaudi that he once made for the Sagrada Familia, because it was an upside-down model, and it was completely made of strings and little bags of sand to keep the string nicely poised. He used this image, he mirrored it with a mirror underneath and used it as the basis for his structural, sort of fundamentals of the Sagrada Familia. That's a really interesting thing, it's also almost like a tool that creates curves, and in this time, in this day and age you probably have a computer to fill this function. What's really charming of course, is that he managed to do it so analogue.

Emilie Chalcraft: So what about the idea that art nouveau was an era where craft and process were quite important, did you think about those things as well?

Sarah van Gameren: I guess that is something that is very fitting in our studio mentality in general, you know? Our processes are, or our projects are very much about process, and about experimentation and about pushing to the borders of science. Our Blueprint project is a really good example of where, on the one hand, nature is really in play, and on the other hand it really pushes things that in the art nouveau era were also pushed, like glazes and so on. This case is really about exposure through UV light.

Tim Simpson: But there is also really a tangent there with our work and the work of the art nouveau, because in some ways we're completely opposite. Because with the artists of the art nouveau, you really see that they wanted to make an interpretation of natural forms in a way that you're very aware of the maker leaving their mark, and that's actually quite opposite to our approach. We are somehow, you could say we're a little bit hands-off, or we are often trying to sort of create distance between our hands and the things that we make.

Sarah van Gameren: And on the other hand, I find also that it has a more direct link to nature, because we use the direct specimen of the vases, but also in this work very much we show almost a sort of natural phenomenon of reflection and symmetry.

Emilie Chalcraft: Did the idea for the installation form itself quite quickly?

Sarah van Gameren: Yeah, it goes sort of back and forth and sometimes, because there are always so many ingredients in our work, every project has more layers than one – technical, but also conceptual.

Emilie Chalcraft: But compared to some of your other projects this one is really simple, there is less science, chemical reactions and all that kind of thing.

Tim Simpson: But what it did have though is some learning through experimentation and really practicing, and we were building a lot of mock-ups. Maybe in principle it's simple, but actually how the light works is something that took a long time to develop. Because when you enter the space the light source is completely invisible, it's only when you lean over – and there is a good reason for that, because if you do see any of the light itself your pupil dilates and it adjusts to – or closes, sorry – the reflection. If you try it actually, you can put a camera over and the camera works the same way and you can't actually photograph the reflection.

Sarah van Gameren: Certain angles are much more effective, like if you go lower to the water surface you get much more effective angles, so we had to make it quite long. All these kind of things, it's like, the usual materials we work with, like the plaster, has been replaced with immaterial materials like light, and there's water of course. It's completely different palette to use. But in a way we do the same thing again – it's still about tweaking materials and trying to make them all come together in a particular moment in the most perfect way, but hands off.

Emilie Chalcraft: And the light is supposed to recreate the cellars and the darkness of the cellars in Epernay. There are plans to actually install Lost Time in the Perrier-Jouët cellars, right?

Tim Simpson: Yeah, well it's naturally a very damp environment. Actually, this whole idea of reflection came from that experience of seeing the still puddles in the cellars, so it is there because the walls are chalk and they have moisture that is there. We've been before to do photo shoots to sort of put a focus on the things that inspired us, and we've already actually flooded the cellars, a really good day where we were taking gallons of water. I was really surprised they let us do it but they did, they let us really flood it, and we were taking these kind of completely mirrored images which were actually quite constructed, in a really fun way, but they were constructed. So those puddles are there, and I think we can actually go even further in the cellars because there is the length, and we had to do the length because it's caves, it's sort of corridors almost, and we know we can flood it. I think it's really at home there, I think it would be really nice.

Emilie Chalcraft: So it could get extended to be even longer?

Tim Simpson: Yeah exactly, yeah.

Emilie Chalcraft: You were saying about process being important to your work. Slow design is quite a buzzword these days, and the idea of looking into craft and process more. Is that something you are interested in or align yourself with at all?

Sarah van Gameren: We're not against production for royalties at all. At this moment our journey, or our path, was different somehow, but we can also really imagine treating industrial production in a very similar way to how we create our installations right now. It's a different thing that holds things together with us. Like, the conceptual backbone has more to do with things like the transformation and the moment of the creation of something. And also, how you shift from an end product to the moment that you create something because it might have more value, and in a way this immaterial approach is also one of these, it's a solution to that hypothesis in a way, you know?

Emilie Chalcraft: A lot of designers are now interested in designing experiences rather than objects, and this seems to be very much an experience rather than a tangible thing. Is it something you would want to do again?

Tim Simpson: Yeah we're really at home in experiences. We like the idea of the timeline, or the idea that you can deliver something in a very controlled way or be the author of how you deliver an experience. So yeah, that's maybe not such a tangible concept with something static, but actually there are ways that that is present in our work. So for instance, if you take one of the Blueware vases, there are cues that we leave behind that explain how that thing came into being, or cues like little pieces of tape.

Emilie Chalcraft: Yeah, I noticed that, I wondered why you kept those leftover marks from the sticky tape on the vases.

Tim Simpson: Yeah, we choose to sort of describe – it's not something you see immediately but there is the hope, in how you interact with it, that there is a level of understanding that reveals itself. You can also do that in experiences, in spaces, you can be in control of timing. We have been talking about how there was this great moment when we hung the work, there was a moment when we filled it with water and everybody came in and sat there and saw the work just kind of appear as a drizzle that got bigger and bigger.

I realised afterwards that sort of genesis of the work, and it is there now, you can as a visitor disturb the water, and people have been doing that and it means that someone comes in and they encounter the thing maybe appearing or maybe disappearing, and in that respect it really works. Although, it would have been really cool to have just a drainage hole in the middle and have the thing constantly kind of drain and fill, or something that was disturbing the surface, because then you become really aware of its fragility.

Sarah van Gameren: That might be something for the next project, you know? Our projects tend to evolve, and it's not like a one off, we in no way want to make one installational statement and then not do anything with that anymore. The next step would be to show this in a different scale and a different context, and yeah, maybe think of a product for example, things to keep going.