Photographs depicting examples of unsung architecture from around London chosen by architecture critics are on show at the Design Museum in London (+ slideshow).

Curated by independent writer, editor and curator Elias Redstone, the series of original images by photographer Theo Simpson documents overlooked buildings and infrastructure, including an oil refinery jetty, a bus garage and a cemetery.

The ten colour offset prints are on display in the Design Museum's Café and Tank space until 22 July and have been compiled in a journal published by Theo Simpson and graphic designer Ben Mclaughlin's publishing company, Mass Observation.

We recently published a set of photographs by Alastair Philip Wiper of the world's largest solar furnace and wave-reflecting chambers and Belgian photographer Jan Kempenaers documented a series of World War Two monuments in Yugoslavia.

See more photography projects on Dezeen »

See all stories about the Design Museum »

Here is a selection of photographs from the exhibition, with the explanatory texts from the critics:

Sam Jacob of FAT, a regular contributor to Dezeen's opinion column, nominated Welbeck Street Car Park in Marlyebone.

Its neighbour is buried beneath Cavendish Square; modern necessity camouflaged beneath apparent historicism. But Welbeck Street is qualmless, a multistory car park celebrating itself as though it were the crowning glory of civilisation. Designed for Debenhams in 1971, it sits like a block-sized sculpture, its elongated diamond-shaped prefabricated concrete panels locked together into mesmeric and scaleless pattern that genuflects to the oddities of its historical boundary.

It is part of a small gang, a batch of buildings produced in a small window when car parks were treated as civic monuments, significant structures that expressed the modernity of the moment. This moment saw a coincidence of the tail end of brutalism and the megastructure along with enthusiasms for grand infrastructural highway planning.

Of course all of those things – cars, architecture, planning, concrete – soon found themselves if not blamed for the collapse of society at least tarnished with doubt, falling on the wrong side of every contemporary ideological debate.

Blampied's architecture explores and expresses the possibilities of the multistory car park. Its frame remains open to the elements, a giant grill that ventilates fumes from the buildings interior while also, perhaps, referring to a cars radiator grill. It is simultaneously practical and symbolic. Its rawness casts it as part of the infrastructural landscape: highway engineered into vertical stack. But here infrastructure is handled with such delicacy that all its rawness is elevated to sublime beauty.

Welbeck Street Car Park should be regarded along with other great structures occurring at the intersection of transport and architecture, alongside Gilbert Scott's St Pancras, Brunel's train sheds and Grand Central Station. It also stands as a template for a problem that is not going to disappear any time soon. The building acts as an interface between cars and the city. It resolves this often troubling relationship beautifully, a structure for cars articulated as a fully urban phenomenon.

Tom Dyckhoff of the BBC Culture Show selected Berthold Lubetkin's Bevin Court flats.

It felt a little like the white rabbit falling down the hole in Alice in Wonderland; only we fell up. It was the mid-1990s. We were at university, on an architecture field trip, trudging past Islington's Farrow & Ball-ed brick townhouses and cappuccino-selling cafes (flat whites hadn’t been invented yet). Yuppies. We still called them yuppies, then.

Our tutor was a Marxist; he was having none of this. He marched his comrades, who, by now, were looking a little green with envy, down Percy Street (more posh townhouses), turned right, ta-dah! Oh... Is that it? A block of flats. And…? Designed by Berthold Lubetkin in the 1950s, we obediently scribbled in our notebooks. Yes, we get the message: we bothered to build homes for the proletariat back then.

It was originally to be called Lenin Court, containing a statue of the Soviet leader, until geopolitics shifted. Very interesting. But, basically, so what? Still not as nice as those Georgian houses. He continued: "Council cut the budget, usual story, so Lubetkin scaled back the ambition. Apart from..."

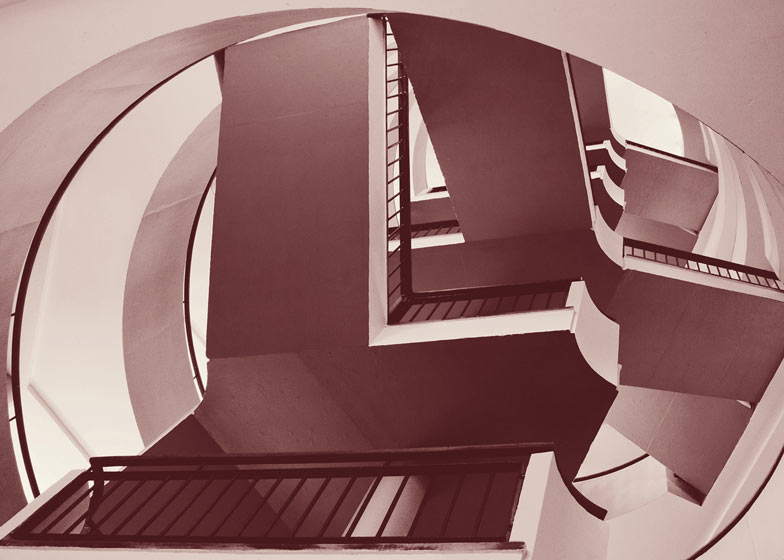

Our tutor opened the block's little entrance door. That one single act will stay with me till I die. It was as if our tutor had slipped us all a tab of acid. We walked in and entered... what? Another universe. Another dimension. Whoosh. That staircase! Now, most staircases in postwar blocks of flats are nothing to write home about. This one, though, was plucked from an Escher print. We scampered up, dizzy, eyes wide open. Imagine coming home from work to this. Imagine popping out for a pint of milk. Going to school. Those Georgian houses didn’t have a staircase like this. Our tutor smiled. This was what architecture was all about. We got the message.

The Cabmen’s Shelter that provided refreshments to Victorian horse-drawn cab drivers was chosen by Oliver Wainwright of The Guardian.

Looking like a cross between a quaint country cricket pavilion and a large garden shed, the Cabmen's Shelter is an enigmatic part of the London streetscape. With its green-painted timber panelled walls, pitched tiled rooftop and decorative air vent poking out of the top, it squats at the side of the road like an emerald Tardis, waiting to transport you back to Victorian London.

There are only 13 of these mysterious structures left, scattered from Chelsea Embankment to Russell Square, all of which are now Grade II listed, but at their height there were over 60 across the city, built at a cost of £200 each. They were the product of the Cabmen's Shelter Fund, established in 1875 by the philanthropic Earl of Shaftesbury to provide "good and wholesome refreshments at moderate prices" for London's army of horse-drawn cab drivers – of which there were 4,600 by 1869.

Law stated that cabbies could not leave their horse and cab at the stand unattended, so they had to pay someone to keep watch if they wanted to go for a break. Providing a place to rest at the head of the taxi rank, the shelters solved this problem. Occupying a place on the public highway, their dimensions could be no larger than the size of a hansom cab and its steed – that is "seven bays long by three bays wide".

Built partly to tempt cabbies away from the pub, the shelters had a moralistic bent: each displays a sign declaring that gambling, swearing and political discussion is strictly forbidden, and alcohol cannot be served. Inside, there is space for 12 people, sitting on benches that run along both walls around a u-shaped Formica-topped table, hinged at the end to allow you to squeeze in. In the corner, an impossibly small kitchen serves up strong tea – and some of the best bacon sarnies in London.

Owen Hatherley of The Guardian nominated an oil refinery jetty in Canvey Island on the Thames estuary.

Canvey Island was 'oil city', a seaside town with a massive sideline in the petrochemical industry. The exceptionally long, spindly, worn jetty that was once part of the Occidental Petroleum site is both a remnant of and currently provides a view of one of the least commented-on but most astonishing 'unknown architectures' around – the buildings of the petrochemical industry, here more specifically, the Coryton refinery in Essex.

Anonymous and hardly even strictly definable as 'architecture', refineries are among the most dreamlike and complex things in the built environment, usually placed at a safe distance from actual cities, the sort of zones where the real workings of the economy, and the structures that house them, can be seen. Refineries themselves are the unacknowledged architectural inspiration for the Lloyds building and much else, bafflingly intricate steel structures made up of dozens of little towers, protrusions and connections, which have a spectacular sense of sheer spatial exuberance and a total lack of the cowardice of so much actual architecture.

Pick a refinery, it doesn't matter which – Wilton, Fawley, or Canvey, where the beach and the jetty provide a view of a site that was mostly established by Mobil in the 1950s; the village of Coryton was razed for the purpose. By day, refineries are stunning enough, but lit up at night, each one is a pocket metropolis, a constructivist's dream of steel, flares and flashing lights, from a distance much more impressive a skyline than many actual cities. Therein, these all-but-illegible, bafflingly complex structures are processing our increasingly irrational oil economy in an appropriately mind-boggling way.

Here's some more information about the exhibition:

Lesser Known Architecture: A Celebration of Underappreciated London Buildings

Lesser Known Architecture is a free exhibition celebrating extraordinary London architecture. Nominated by leading architecture critics, these ten buildings, structures and subways contribute to the mix and diversity of the city but are all too often overlooked and forgotten. Curated by Elias Redstone, Lesser Known Architecture presents an alternative architectural map of the city. Each site has been photographed by Theo Simpson and will be displayed as a series of single colour offset prints in the Design Museum Café and Tank. The installation is designed by Ben Mclaughlin.

The Ten London Buildings Featured and their Nominators:

» Bevin Court nominated by Tom Dyckhoff (BBC Culture Show)

» Brownfield Estate nominated by Owen Hatherley (The Guardian)

» Cabmen’s Shelters nominated by Oliver Wainwright (The Guardian)

» Crystal Palace Subway nominated by Rory Olcayto (The Architects’ Journal)

» London Underground Arcades nominated by Edwin Heathcote (Financial Times)

» Mail Rail nominated by Ellie Stathaki (Wallpaper*)

» Nunhead Cemetery nominated by Hugo MacDonald (Monocle)

» Occidental Oil Refinery Jetty nominated by Owen Hatherley (The Guardian)

» Stockwell Bus Garage nominated by Tom Dyckhoff (BBC Culture Show)

» Welbeck Street Car Park nominated by Sam Jacob (Dezeen / Art Review)

Each nominator has written an overview of their buildings historical and design credentials that will be published in the accompanying journal, Lesser Known Architecture, Vol. 1: London.

The Lesser Known Architecture photographs will also be produced as limited edition prints available to purchase from the Design Museum Shop.

Lesser Known Architecture is part of the London Festival of Architecture 2013.