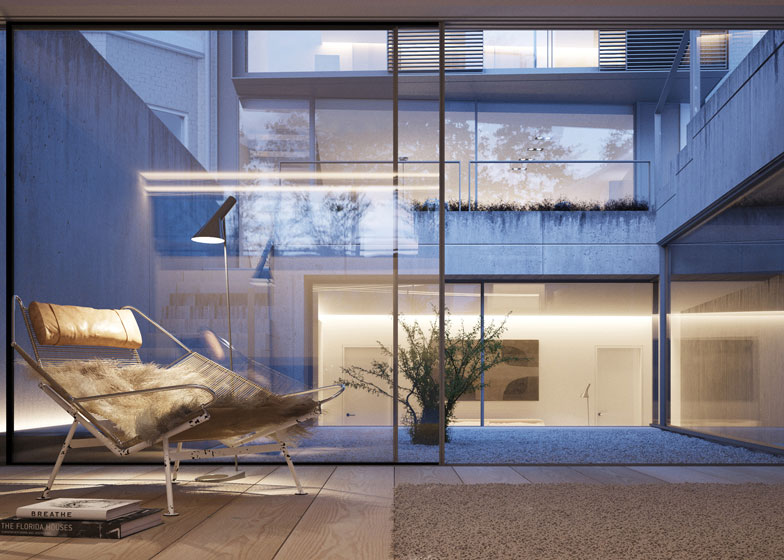

Interview: following the popularity of the hyper-realistic computer renderings of Staithe End house that we published earlier in the month, Henry Goss, the architect and visualiser who produced the renders, talks to Dezeen about how 3D visualisations are becoming indistinguishable from real photographs.

Goss set up architectural visualisation company Goss Visualisations in 2012, having started up his own architectural practice the previous year. In the interview, he reveals that he owes his visualisation style to well-known visualiser Peter Guthrie.

"I got into visualisation because of Peter," Goss says. "Peter pretty much taught me everything I know in 3D Studio Max."

He adds that knowing Guthrie was one of the reasons he decided to set up his own company: "I knew how much Peter was paid for his renders."

Goss goes on to describe how he creates his renders, pointing out that he is unusual in the field because he starts out with Sketch Up. "It's seen as a free bit of Mickey Mouse software," he says. "But in actual fact, it's really good."

Goss says that 3D renders are already almost indistinguishable from photographs, but are being taken to the next level by "the addition of real world imperfections. Scratches in metal, splinters and chips in timber boards, even fingerprints."

However, Goss warns that rendered images can sometimes surpass the photographs of a building once it is completed. "There's always a danger that the client will come along at the end and stick in a whole bunch of crap furniture," he says. "Then the photographs of the building aren't as good as the render and everyone calls you out on it."

Here is a full transcript of the interview:

Ross Bryant: How did you get into visualisation?

Henry Goss: When I've worked in various [architecture offices] in the past, I've always been the graphic person because I always had a good eye for graphics. In quite a lot of these offices there will always be someone who is better at rendering than others and they will become the render bitch – the go-to person. I kind of just enjoyed it as a hobby almost. Also [leading visualisation artist] Peter Guthrie is a friend of mine and I knew how much Peter was paid for his renders!

Ross Bryant: People have compared your rendering style to Guthrie, as well as that of Bertrand Benoit.

Henry Goss: Peter Guthrie and Bertrand Benoit are friends of mine. I got into visualisation because of Peter. He used to be an architect and then went down the visualisation route. I set up my practice at the same time and I've learnt 3D through him. That's why a lot of people have compared my style to Peter's; Peter pretty much taught me everything I know in 3D Studio Max.

Ross Bryant: How would you describe your visualisation style? How does it differ from other styles?

Henry Goss: I would describe both Peter's visualisation style, and by association mine, as photographic. I generally think of architectural visualisation in three categories, all three of which are necessary to achieve a high-end result:

1. A technical understanding of the software, this may be obvious but it is impossible to have proper control without having a fairly good knowledge of the tools you are using.

2. An understanding of architecture. An architectural visualiser who has no real appreciation of their subject matter will never grasp the subtleties of what they are attempting to recreate.

3. An understanding of architectural photography. This is often the most overlooked and potentially most important aspect of the three.

Ross Bryant: What software do you use?

Henry Goss: Largely I use SketchUp for modelling, 3D Studio Max and V-ray for rendering and Photoshop and Light Room for post-production. I also use Peter's HDRI Skies exclusively these days, along with most of the architectural visualisation industry. Obviously, to make the images work at this level, you have all sorts of plug-ins but that's essentially it.

The workflow I use isn't actually used that much in the visualisation world; there's a certain snobbery in the visualisation world about SketchUp because it's seen as a free bit of Mickey Mouse crap software that architects use because they are too stupid to use real 3D programmes. But in actual fact, it's really good.

Ross Bryant: Did your visualisation skills help you when you set up your own practice?

Henry Goss: When I started getting better at it and I was going to set up my own practice, I was like: "Well shit, if I'm going to set up my own practice, I need this level of quality." And also if you haven't built a project, you need high-end visualisations to get you noticed in the industry because that's what people expect these days.

Ross Bryant: Do you present photorealistic renderings to your clients from the outset?

Henry Goss: Early on, you don't want to tie your own mind or your client's mind down to a specific photo-realistic space, you want it to be much more about the early architectural image and the evocation of space and the ethereal nature of light. Later on, when the photorealistic render comes in, it's partly marketing and partly a fascination with the fact that we have the technology that can achieve this.

Ross Bryant: Why go to so much trouble with the images?

Henry Goss: Two reasons: Firstly publicity. Being a relatively young architectural practice our built portfolio is relatively small. The second reason is that I'm secretly a bit of a geek and I simply enjoy it.

Ross Bryant: How long does each image take?

Henry Goss: It's hard to say as the set up for each job is so different. A simple render with few materials may only take a few days to a week to produce several images. A render with full CG environment such as Staithe End including scatter objects, grass, trees, gravel and procedural textures can take significantly longer. Staithe End was developed gradually over a period of about three months.

Ross Bryant: Why are there no people in the Staithe End renderings?

Henry Goss: There are two main ways of adding people to renders, either by rendering a 3D modelled person or by montage in post production. The human brain is highly tuned to pick up subtle nuances of human appearance and movement and therefore it's very difficult to achieve a convincing result. I usually add people if the message trying to be conveyed is about use and lifestyle, but I feel that, as with a lot of architectural photography, sometimes the pure nature of the architecture itself is better represented laid bare.

Ross Bryant: How soon will visualisations be indistinguishable from real photos? Or have we already reached that point?

Henry Goss: I think the likes of Peter Guthrie and Bertrand Benoit are pretty much there already, obviously it depends on the resolution of the image/photo. The thing that's currently taking photorealism in architectural visualisation to the next level, most strikingly exemplified by the work of Bertrand Benoit, is the addition of real-world imperfections. Scratches in metal, splinters and chips in timber boards, even fingerprints.

Ross Bryant: Do photorealistic visualisations – and the way they are published on the internet - change the way people perceive architecture?

Henry Goss: I'm sure they do change people's perception and I suspect for the architectural purist it's a negative thing. Architecture as fashion and commodity has been widely discussed and the rendered image has been lambasted for perpetuating the notion of style over substance and image over experience. I even sometimes get people, possibly being tongue-in-cheek, saying, "you don't need to go though the hassle of building that, you've got the pictures already." It's a difficult one as even though I like to think I interrogate architecture, I still regularly find myself flicking through a journal or website and only stopping when I'm seduced by an easily accessible sexy-looking image.

Ross Bryant: Can renderings look better than the finished building?

Henry Goss: The danger is that the client comes along at the end of it, sticks in a whole bunch of crap furniture and then the photographs of the building aren't as good as the render and everyone calls you out on it.

Ross Bryant: Why don't the big architecture firms use photorealistic renderings to illustrate major proposals?

Henry Goss: The big companies are aspiring to a different artistic level, a different kind of integrity and so they don't need the top end visualisations to convey their message. Any architectural image is essentially about conveying a message and in the architectural sketch you might be conveying the essence of a scheme in the simplest possible way.

I'm doing some renders at the moment for an office space and it's essentially a developer who wants a wide-angled perspective so that they can say that's where you sit and have your coffee, that's where the sun comes in and there's the strategically placed child with an obligatory balloon. But that's the shot that shows everything, it shows the fact of what the space is, but it doesn't necessarily show what it feels like. The high-end renders don't necessarily show everything but they're more evocative. You're cropping down and trying to capture the essence of the space.

Ross Bryant: Where is architectural visualisation heading next?

Henry Goss: I see the whole industry heading in the direction where you have a single [digital] model [of a building]. This happens in a lot of the big commercial practices. They have a single model, which not only has all the architectural components, building services components and the structure and coordination of all things, but it's also testing lighting levels and testing environmental factors.

Computer-aided design has now reached a level where it's all becoming very integrated. The visualisation isn't purely visualisation anymore – you can actually use the same [digital] models with the same lighting rigs to test real-life environments and real-life situations. I use it to a small degree but people take it to a greater degree where they are really testing the actual lux levels in a space on a full environmental model.

See our story on Staithe End House by Henry Goss Architects»

See all our architecture stories»