Interview: renderings are now as convincing as reality and are changing the way people perceive architecture, according to architectural visualisation artist Peter Guthrie. "It allows for greater conversation about the built environment," he says in this interview. "Most people are familiar with computer images but would find it harder to interpret a line drawing." (+ slideshow).

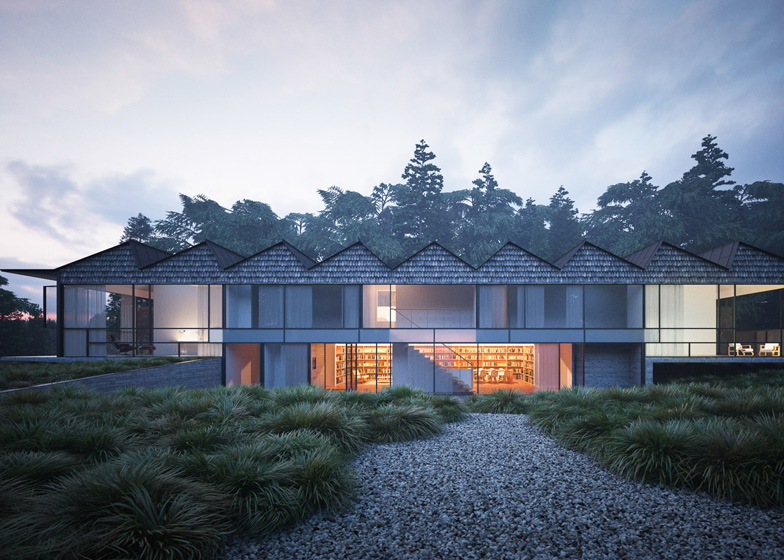

London-based Guthrie is widely regarded as the leading exponent of hyper-realistic imagery, and has produced image sets for projects including a Suffolk house by Ström Architects and Claesson Koivisto Rune's prefabricated home.

"I try to make atmospheric, memorable images without using too many post-production tricks," Guthrie says. "Other visualisers perhaps take their inspiration from film and video games, but that isn't an aesthetic I'm drawn to."

When asked whether we've reached the point where renderings are indistinguishable from photographs, he replied: "I think we have... The 2013 Ikea catalogue has a surprising number of visualisations in it and most people are none the wiser."

Guthrie believes that people are now so used to computer imagery thanks to movies and computer games that they can "read" architectural renderings more readily than line drawings or sketches. "It makes un-built architecture more immediate and allows for greater conversation about the built environment," he says.

He adds: "Most people these days are incredibly familiar with computer generated images (although they are usually in the form of feature films or computer games) but would find it harder to interpret a line drawing or watercolour of a proposed building."

Boundaries are now becoming so blurred that skilled visualisers are now being employed to make it appear that unbuilt projects were actually realised, he said. "I've even had architects in the past ask me to render unbuilt house designs from their archives," he says.

Here is a full transcript of the interview:

Ross Bryant: How did you get into visualisations?

Peter Guthrie: I studied architecture in Edinburgh and worked for Richard Murphy Architects for about five years after completing my degree. During that time I became more and more interested in both photography and visualisation and eventually decided to make the switch.

Ross Bryant: Are there other visualisers that have inspired or informed your work?

Peter Guthrie: Within visualisation I'm inspired by people like Alex Roman and Bertrand Benoit for their pioneering techniques. You need to have a healthy interest in all the technical geeky things in 3D visualisation and it's important to stay up to date. Most of my inspiration for making images of architecture though comes from architectural photography.

Ross Bryant: How would you describe your visualisation style? Does it differ from other styles?

Peter Guthrie: I hope it is seen as being closer to architectural photography, that's what I am aiming for anyway. Other visualisers perhaps take their inspiration from film and video games, which still results in captivating beautiful images but it isn't an aesthetic I'm drawn to. I still try to make atmospheric, memorable images but without using too many post-production tricks.

Ross Bryant: What software do you use?

Peter Guthrie: SketchUp because it's so quick, easy and so suited to the changeable nature of architectural design. Making the model myself builds familiarity with the project and I think that is a very important part in the whole process of coming up with good compositions, a bit like a photographer walking round a building to get an idea for what he wants to shoot.

3ds Max is the main base for a whole raft of plugins such as V-Ray. The raw rendered images are then treated much like a raw file would be in digital photography - imported into Lightroom to work on colours, exposure, dodging and burning as well as graduated filters etc.

This post production process is probably very different to the vast majority of people working in 3D visualisation and I think this reflects the fact that I have a background in architecture and photography - it's just a workflow I feel comfortable with.

Ross Bryant: Why go to so much trouble with the images? Where's the value?

Peter Guthrie: Because I enjoy it. For me personally, I just like making good images that I'm proud of and that I can look back at in a couple of years' time and still enjoy. For some clients, like for example Ström Architects whose Suffolk House project you featured on Dezeen back in August, there is a lot of value in making images of as yet un-built designs to help them establish their practices.

There are projects I have worked on which never actually got built in the end, so the renders then become even more important as a record of the design. I've even had architects in the past ask me to render unbuilt house designs from their archives. It's true that on some of my older projects I could have got away with a lot less and my client probably would still have been perfectly happy, but often I use a project as an excuse to learn a new skill or develop a new technique.

Ross Bryant: How long does each image take you?

Peter Guthrie: Typically maybe a month for five or six images of a house. The museum project I worked on with Thomas Phifer & Partners in New York lasted three months but we ended up with 24 images in total.

Ross Bryant: Are high-end visualisations lucrative?

Peter Guthrie: They can be, there are a lot of visualisation studios around these days and there seems to be a lot of work for freelancers. It can be tricky finding the balance between interesting work and work that pays well.

Ross Bryant: Do you think that we've reached the point where visualisations are indistinguishable from real photos?

Peter Guthrie: I think we have, but certain types of shot are more successful than others. You can get away with a lot if the overall image has a photographic quality, if the composition and lighting are convincing. The 2013 Ikea catalogue has a surprising number of visualisations in it and most people are none the wiser.

Ross Bryant: Can renderings look better than the finished building?

Peter Guthrie: Photographs of a completed building often look better than the building does in real life. Whether or not renderings do is part of the same argument isn't it?

Ross Bryant: Architect and visualiser Henry Goss introduces real world imperfections into his architectural visualisations. What's your view on this?

Peter Guthrie: I've always been interested in materiality in architecture so it is important for me to spend time working on making materials look realistic. Taking materials to the next level is about introducing the variety of texture and lack of uniformity that you see in real life situations. You can take the realism of individual materials to a very high level without resorting to making things deliberately worn and dirty as you often see in video games. I'm yet to meet an architect who wants their new design to look weathered before it has even been built!

Adding small details can also add greatly to the realism of an image. It sounds crazy I know, but I like to model double glazing accurately so that you get the subtle double reflections that you see in real life.

Ross Bryant: Do photorealistic visualisations and the way they are published on the internet change the way people perceive architecture?

Peter Guthrie: I'm sure it does, at least in that it makes un-built architecture more immediate and allows for greater conversation about the built environment. Most people these days are incredibly familiar with computer generated images (although they are usually in the form of feature films or computer games) but would find it harder to interpret a line drawing or watercolour of a proposed building.

Ross Bryant: Do you think that the big architectural firms will begin to use photorealistic renderings to illustrate major proposals?

Peter Guthrie: They already have that capability, but good designers will know what is appropriate to the current stage of the design they are showing. It really depends how fixed the designs are, and how much time they want to invest in renders. Sometimes architects are deliberately hesitant about showing too much detail as it can make planners or clients question how much scope there is for making changes.

Ross Bryant: Where is architectural visualisation heading next?

Peter Guthrie: Actually I'm not even that comfortable with the title architectural visualiser as architectural visualisation is too often seen as a service industry where the most valuable aspect is how quickly images can be produced. I think as the industry matures we are starting to see more distinct styles develop. Companies and individuals have the confidence to lead the artistic direction of an image, and clients are employing them because they can offer something different. Thankfully these days potential clients are more aware of the type of work I do.