3D-printed human cells could "replace animal testing"

News: 3D-printed human cells could replace the need for animal testing of new drugs within five years, according to a pioneering bio-printing expert at the 3D Printshow in London, which opens today.

"It lends itself strongly to replace animal testing," said bioengineering PhD student Alan Faulkner-Jones of Heriot Watt University in Edinburgh. "If it gets to be as accurate as it should be, there would be no need to test on animals."

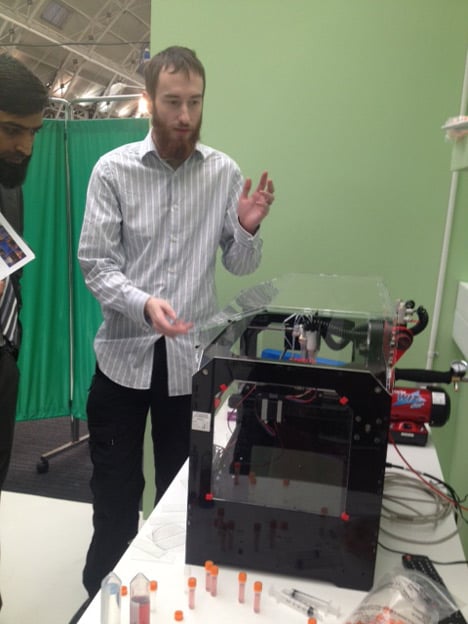

Faulkner-Jones spoke to Dezeen while demonstrating the technology at the 3D Printshow in London this week as part of the 3D Printshow Hospital, a feature designed to showcase medical uses of 3D printing.

Using a bio-printer made from a hacked MakerBot printer, Faulkner-Jones is demonstrating how human stem cells can be successfully printed to create micro-tissues and micro-organs that can be used to test drugs.

The technology could be ready to replace animal testing within five years, he believes. "The micro-tissues I think would be in the order of five years away hopefully, if we carry on at the pace we are now," he said. "You could even test personalised drugs. So you'd be able to use cells of the person that is ill and create specific micro-tissues that would replicate their response, rather than the response of a generic human.

Image of animal testing courtesy of Shutterstock.

Here's an edited transcript of the interview with Faulkner-Jones:

Marcus Fairs: Tell us who you are and what this project is all about.

Alan Faulkner-Jones: I'm Alan Faulkner-Jones from Heriot Watt University in Edinburgh and we're working on this bio-printer to produce small human micro-tissues for drug testing and drug production to replace animal testing.

Marcus Fairs: There's been a lot of talk about 3D printing of human tissue. How much further forward does this project take the story?

Alan Faulkner-Jones: This is a major breakthrough in the fact that we did more testing than has ever been done before on the exact physiological response of the stem cells to the printing process. A lot of people have tried to do it before and have just checked whether or not they're still alive at the end of the process, but we checked several markers to make sure that they were still physiologically the same cells at the end as they were when they went in. So we checked the potency markers to check the stem cells were still stem cells - because if they're not stem cells then the technology isn't worth anything, because you've changed them by printing. We want it to be as non invasive as possible. So on top of the fact that we've been able to prove that it's over 90% viable, the cells are physiologically identical when they come out of the printing process.

Marcus Fairs: How much does this have in common with a standard 3D printer such as a MakerBot?

Alan Faulkner-Jones: All the iterations of our technology started out as something else. The first generation model was a CNC machine, which was too big. We couldn't do anything with it. So we made a series of these - this is the third one - and you might notice that some of the plastic bits are from a MakerBot.

Marcus Fairs: It's hacked?

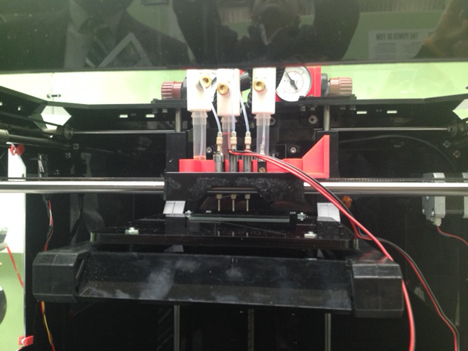

Alan Faulkner-Jones: Yeah. We rebuilt it. It has a completely new control system and everything but the plastic bits and the rails came off a Replicator 1. But the major difference of course is the print head, which is a completely different design. It's a pressurised cartridge system which is fed into a solenoid valve with a nozzle on it. By opening and closing the valve, we can produce different volumes of fluid. And by changing the pressure and the opening time we can control the different size of droplet we produce.

Marcus Fairs: So it's a pneumatic process rather than an extrusion process?

Alan Faulkner-Jones: Yes. The fluid is under pressure.

Marcus Fairs: Is this specifically aimed at the drug testing market?

Alan Faulkner-Jones: I'm aiming it at testing. My supervisor and some of the researchers aren't exactly geared towards it but it lends itself strongly to replace animal testing.

Marcus Fairs: Tell us how that would work, and how soon it could be ready.

Alan Faulkner-Jones: At the moment unfortunately a lot of drugs have to be tested on animals for regulations. You have to prove that it works, which unfortunately leads to the drugs being tailored to the specific animals they're tested on, which won't give you an accurate response for a human. Which is why a lot of money is spent on drugs that don't make it to market.

Marcus Fairs: They work for rabbits but they don't work for people?

Alan Faulkner-Jones: Exactly. So they fail at the last hurdle basically. You've spent so long testing them on animals that they don't work on humans. Or if they do they produce adverse side effects. So the idea is that we would produce micro-tissues of specific organs in the body and then they would have the same reaction to the physiological environment - drugs, everything - as the entire organ would do, but on a much smaller scale.

So you can apply the drug to the micro-tissue and it would give off the same result. So if it killed it or inflamed it, you'd get that response. And you could then connect a series of these micro-organs together into a system that is becoming known as "human on a chip" - so you can find the entire body's reaction to a new drug or chemical.

Marcus Fairs: Tell us more about the human on a chip. Is that a digital chip or a biological one?

Alan Faulkner-Jones: With human on a chip you have areas on this micro-fluidic chip with a synthetic blood supply and nutrients, and introduce the drug inside each chamber, where you have micro organs that represent human organs. So you have one for the liver, the kidney, the lungs, the heart, brain tissue.

Marcus Fairs: So it's like a chip of living tissue?

Alan Faulkner-Jones: Yes. It wold emulate the whole body's response.

Marcus Fairs: And this could eliminate the need for animal testing?

Alan Faulkner-Jones: I hope so yes. If it gets to be as accurate as it should be, there would be no need to test on animals. You could even test personalised drugs. So you'd be able to use cells of the person that is ill and create specific micro-tissues that would replicate their response, rather than the response of a generic human.

Marcus Fairs: How far away is that?

Alan Faulkner-Jones: The micro-tissues I think would be in the order of five years away hopefully, if we carry on at the pace we are now. It's just a matter of sorting out cell ratios at this point. We can produce cells, we just need to make sure we can get the physiological response. There are certain structures in the organs that are quite difficult to reproduce at a small level.