Portuguese architect Álvaro Fernandes Andrade has completed a training facility for Olympic-standard rowers where angular white volumes snake across a tiered landscape of grassy slopes and dry-stone walls (+ slideshow).

The Pocinho Centre for High Performance Rowing is located in Portugal's Douro Valley, a wine region that is classified as a World Heritage Site, so Andrade designed a structure with most of its body buried underground.

The building is divided into three zones that each accommodate different activities. The first and largest section is the accommodation, which comprises a total of 130 dormitories that stagger down the hillside.

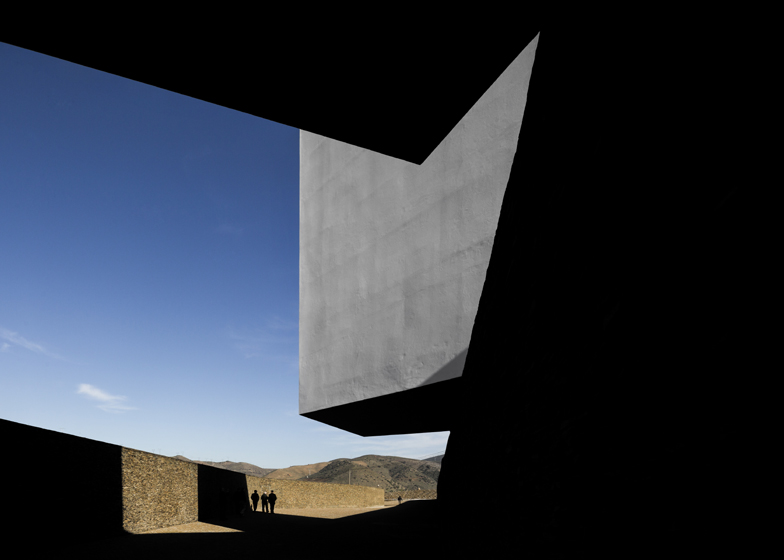

The other two sections are labelled as "social" and "training" and are housed within the white-rendered concrete blocks that jerk across the surface of the complex like a huge faceted serpent.

"The two more dynamic and productive major areas impose themselves on the landscape, spreading out along several different levels in large white, formally dissimilar and volumetrically complex structures," said the architect.

The entrance to the complex sits within a sunken tunnel. This runs parallel with the rows of staggered dormitories, which are revealed above ground as descending roof terraces with long narrow skylights.

"Terraces and clusters of buildings, abrupt, tense connections tearing through terraces, steep ramps, and stairs between walls, usually in the open, are all covered here in order to meet the needs of the program," said Andrade.

Communal areas where resident athletes can relax are located at the highest point of the hillside to allow views out over the scenic countryside, while training and workout areas are tucked away behind.

Currently the facility accommodates training for up to 130 people, but could be extended in the future to allow this number to increase to 220.

Photography is by Fernando Guerra.

Here's a project description written by Álvaro Fernandes Andrade and translated into English by Jed Barahal:

High Performance Rowing Centre, Pocinho, Foz Coa, Portugal

Memory

The guiding principles and strategies of the project for the Pocinho Centre for High Performance Rowing play their part in a dense and inextricable mixture that includes the peculiarities and identity of a pre-existing, specific "place", the characteristics and demands of a very recent program, and the needs and wants of the architectural act.

If we fall back on references that are closest to us, such as Fernando Tavora (with whom I was lucky to have studied in my first year of college, the last year he taught at the Faculty of Architecture of the University of Porto), along with all that Siza Vieira thought and said (a lot) and wrote (not a lot, but much better designed and engineered), we need to appreciate the various meanings contained within this "place", in particular as a cultural "thing" and, most notably here, the landscape of the Douro River Valley as a World Heritage Site, and the specific ancestral expression of man's intervention and transformation of the landscape.

For the demands of a very recent program, as is this case of a complex developed specifically for training and preparing high performance, Olympic level athletes, there is no or very little "historical precedent to put the words in the mouth of the president," as Sting put it a few years ago. For architects, in general, this only makes the challenge of the project more exciting. This case was no different.

As regards the needs and wants of designing (as if architecture were not also a conscious act of will and innovation), they in turn also played out within "pre-existing" requisites (such as ensuring "Mobility and Accessibility for All", and the essential values of "Sustainable Development"), and those that materialised during the design process, such as the problem of taking on a large program (8,000 m2/84 rooms/approx. 130 users), with the prospect of future expansion (up to 11,500m2/170 rooms/approx. 225 users) in a possible subsequent expansion phase of the housing area, without a significant impact on size and the landscape.

In the resulting complex interaction, the decision to structure the program in three fundamental components (Social Zone, Housing Zone and Training Zone) merges with the (re-)interpretation of two elements of secular construction of the Douro landscape: the ubiquitous terracing, a recurring form of "inhabiting" this markedly sloping valley (read here "inhabit " as "extracting bread from the earth"), and the large white bulks of the buildings set in the landscape, in particular of the large wine-producing estates, formally complex and varying in size (often resulting from building over a long period of time, due to successive changes in the requirements of working the land).

Between them we find terraces and clusters of buildings (often between them and the river as well), abrupt, tense connections tearing through terraces, steep ramps, and stairs between walls, usually in the open, are covered here in order to meet the needs of the program.

But the choice of structuring/separating the program into three distinct zones is also a help in the effort to place the most-used zones on the same level, while minimising eventual movements between levels, something that surely will not be foreign to the history of physical and spatial transformation of this valley, which we are only trying to reinterpret.

The above is also an expression of the typical understanding of the history of architecture at the Faculty of Architecture of the University of Porto... not as an end in itself, but as one more element brought to the drawing board/computer, in coordination with other design problems.

Concurrently, the set of aforementioned options, accepted or adopted, allowed for a more organised coordination of the principles of passive management of the building’s energy. In the housing area, used for longer periods of time with less physical activity, the "skin" exposed to the elements has been limited , and the structures leant up against and dug into the ground (as the Eskimos do with their igloos). Rooftop greenery reinforces this insulation. Complementing the use of passive solar energy, the rooms have skylights facing south, in search of the sun, taking into account the general Northern exposure of the entire complex. The walls of the rooms, in naked concrete, reinforce simultaneously the meaning of "land", "home", of protection, of this component of the program, and allow for optimal storage of solar thermal energy captured through the skylights which, during the heat of the Douro summer, are shaded from the outside.

As a bonus, stars can be seen from the beds. And in conjunction with the necessary windows and welcome natural light in the halls leading to the rooms, we have made it possible that, from outside, the shale terraces and what covers them "float", consciously rejecting any direct imitation. Even the irregularity of the plans of the housing area, rather than contributing to the "irony" of imitation, serves the relationship between a systematic and repetitive component of the program (the rooms cells), and the need for close proximity of these with other areas, whether for servicing the rooms themselves (kitchenettes, small social areas, laundry rooms for individual use, etc.) or for services such as machinery, equipment, storage, etc. This irregularity has a role in the interplay between repetition and identity, fragmenting the protracted spaces and long visually undifferentiated corridors, punctuating them with limits of perspective and unique spaces as they expand.

However, even considering the above, this combination of conditions and design options does not prevent the quantitatively most significant component of the program from being "diluted" into the land/landscape, and the future expansion of the desired number of rooms at the centre from being carried out without major disruptions to the general logic of the project (also because the whole project has been developed taking into account the prospect of maximum use of the land).

It may be added, in reference to this component of the program, that in spite of the limited size of the housing area, all of the rooms built at the level of the access hall can be used by athletes in wheelchairs. Just by removing and placing the supports in the bathrooms of these rooms, athletes with physical constraints may choose their rooms, and they can lodge in the same areas as the rest of their team, without having to be relegated to some convenient corner, in rooms "for the disabled".

Having defined the structures and the contours of the land, the site and the programmatic component of "lodging", the two other more dynamic and "productive" major areas (Social Zone and Training Zone), impose themselves on the landscape, spreading out along several different levels in large white, formally dissimilar and volumetrically complex structures.

Adopting a language and expressiveness of their own, and emerging as the most visible components of the project, they express the meaning of project and transformation, in contrast with the "shyness" of the terraces. Developed in conjunction with research on the characteristics and physical needs of each of the programmatic components, they emphasise the particularities of the relationship of these with the setting.

The communal areas for rest and relaxation take over the higher levels and look out over the countryside. Turning their backs to these are the training and workout areas, in an attempt to reflect the logic of effort and concentration that high performance athletes know so well.

Along with these particularities, they also foster different interactions with the previously outlined principles, in interdependent relationships of cause and effect. Formal complexity coordinates the development of a specific image with, for example, the freedom to control solar exposure through windows between summer and winter, or from east to west. In other words, the ostensible randomness of shape actually guarantees direct exposure to the winter sun through glass, as well as shade from the excruciating heat of summer. An effort was made to insure respect for the particularities of this system of construction, an element that is inseparable from questions of language that come into play. With a system of construction that includes facades and ventilated rooftops, double thermal insulation, and a system of "dry-wall construction", we have attempted to equate questions of sustainable development, allowing, for example, for the disassembly and recycling of materials at the end of their life cycle.

An engaging and exciting challenge for the architect, the centre was also a challenge in investigation of the forms and processes of the integration of the specificity of "new" themes, such as accessibility and sustainability, which we seek to define, indefinitely, as... architecture. Only architecture. Without labels. Without adding labels that only lessen it, such as "environmental", "green", "accessible", or "sustainable". If there is anything missing from this work of architecture, it is those who, I think, architects really work for: the people who will use it.