Google Glass was designed through "sketching by hand" says lead designer

Interview: when designer Isabelle Olsson joined the secret Google X lab in 2011, Google Glass looked like a cross between a scuba mask and a cellphone. In this exclusive interview, Olsson tells Dezeen how she turned the clunky prototype into something "beautiful and comfortable". Update: this interview is featured in Dezeen Book of Interviews, which is on sale now for £12.

"When I first joined I had no idea what I was going to work on," she said, speaking via a Google Hangout video link from New York. "Then I walked into a room full of engineers wearing a prototype of the glasses. These were very crude 3D-printed frames with a cellphone battery strapped to the legs. They weighed about 200 grams."

She was given her first brief, which was "to make this beautiful and comfortable".

"My initial goal was: how do we make this incredibly light? I set up three design principles; if you have something that is very complex you need to stick to some principles. The first was lightness, the second was simplicity and the third scalability".

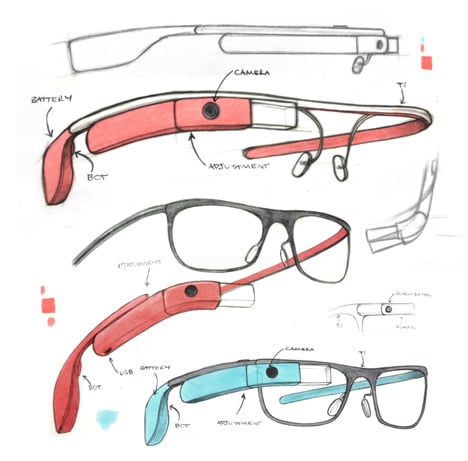

Despite the technology available to her at Google, Olsson took a fairly traditional approach to refining the design of Glass, which is a computer that is worn like a pair of glasses and features a tiny optical display mounted in front of one eye.

"We would first start by sketching by hand," she said. "Then we would draw in Illustrator or a 2D programme. Then we would laser-cut these shapes in paper."

"After many iterations the team would start to make models in a harder material, like plastic. And then we got into laser-cutting metals. So it was an intricate, long, back-and-forth process."

This painstaking, craft-led approach was essential when designing something that will be worn on the face, Olsson believes.

"A 0.2mm height difference makes a complete difference to the way they look on your face," she said. "What looks good on the computer doesn't necessarily translate, especially with something that goes on your face. So as soon as you have an idea you need to prototype it. The next stage is about trying it on a couple of people too because something like this needs to fit a wide range of people."

Olssen grew up in Sweden and studied fine arts and industrial design at Lund University. She later worked for industrial design studio Fuseproject in San Francisco, where she worked on products including Samsung televisions, the Nook Color ebook reader and VerBien, a range of free spectacles developed for children in Mexico.

She now leads a team of less than ten designers at Google X, including "graphic designers, space and interior designers, design strategists and industrial designers but also people who work in the fashion industry".

She says: "The funny thing is almost nobody on the design team has a technology background, which is very unusual for a tech company. But the great thing about that is that it keeps us grounded and keeps us thinking about it from a lifestyle product standpoint."

With Glass, she was keen to ensure the product was as adaptable and accessible as possible, to ensure it could reach a wide range of potential users. "From the very beginning we designed Glass to be modular and to evolve over time," she said.

This week saw the launch of a range of spectacles and sunglasses that can be used with the existing high-tech Glass product, which clips on the side of the frames. The expanded range of products helps shift what started as a tech product into a lifestyle accessory.

"We're finally at the beginning point of letting people wear what they want to wear," Olsson said. "The frames are accessories so you detach the really expensive and complex technology from the style part: you can have a couple of different frames and you don't need to get another Glass device."

Images are courtesy of Google.

Here's an edited transcript of the interview:

James Pallister: Can you start by telling me a little bit about how you started designing Google Glass?

Isabelle Olsson: Two and a half years ago I had a very simple, concise brief, and it was to make this [prototype of Google Glass] beautiful and comfortable. When I first joined I had no idea what I was going to work on. I just knew I was joining Google X and working on something new and exciting.

Then I walked into a room full of engineers wearing a prototype of the glasses. These were [very crude] 3D-printed frames with a cell-phone battery strapped to the legs. They weighed about 200 grams.

James Pallister: What were your initial design intentions?

Isabelle Olsson: My initial goal was: “how do we make this incredibly light?”. I set up three design principles; if you have something that is very complex you need to stick to some principles. The first was lightness, the second was simplicity and the third scalability.

The first thing that made me nervous was not how are we going to make this technology work but how are we going to be able to make this work for people; how are we going to make people want to wear the glasses? The first thing that came to mind is that when you walk into a glasses store you see hundreds of styles.

From the very beginning we designed this to be modular and be able to evolve over time. So in this version that you have probably seen already, there is this tiny little screw here and that is actually meant to be screwed off and then you can remove this frame and attach different kinds of frames.

James Pallister: You’re launching new prescription frames and sunglasses which fit the Google Glass you launched in 2013?

Isabelle Olsson: Yes. What is really exciting is that this is our first collection of new frames. The frames are accessories so you detach the really expensive and complex technology from the style part: you can have a couple of different frames and you don't need to get another glass device. So we're finally at the beginning point of letting people wear what they want to wear.

James Pallister: How many people were on the team who refined the clunky prototype into what we see today?

Isabelle Olsson: The team started off very, very small: it was like a little science project. As we started to transition it into something that you could actually wear we have grown the team. Our design team is still really small. So in the design team I can count them on my 10 fingers.

James Pallister: What kind of people do you have on your team?

Isabelle Olsson: I really believe in having a mixed team: graphic designers, space and interior designers, design strategists and industrial designers but also people who work in the fashion industry. The funny thing is almost nobody on the design team has a technology background, which is very unusual for a tech company. But the great thing about that is that it keeps us grounded and keeps us thinking about it from a lifestyle product standpoint.

James Pallister: Is that one of the strengths of the team, that you are not too obsessed the technology?

Isabelle Olsson: There’s often the view that designers and engineers have to fight; that there should always be a constant battle. I don't believe that. I think that view belongs in the 1990s.

James Pallister: Are the glasses manufactured by Google?

Isabelle Olsson: They are made in Japan. They are made out beautiful titanium that is extremely lightweight and durable.

James Pallister: With the spectacles and sunglasses, how did you choose which styles to develop?

There actually aren't that many styles out there, so we looked at the most popular styles and condensed then into these really iconic simplified versions of them. Bold for example is great for people that would normally prefer kind of a chunky, square style. Curve, which I'm wearing, is perhaps a little more fashion-forward. And Split is for those who like almost rimless glasses or ones which are lighter on your face. Then Thin is this very classic traditional simple style that doesn't really stand out.

James Pallister: Had you ever designed glasses before?

Isabelle Olsson: I have designed glasses and jewellery. So it wasn't completely new but we did spend a long time refining these. We wanted the shape to be absolutely perfect. A 0.2mm height difference makes a complete difference to the way it looks on your face. Prototyping was absolutely crucial. We also cut paper and used laser cutting and used 3D printing.

James Pallister: Could you explain the design process?

Isabelle Olsson: We would first start with sketching by hand. And then Illustrator or a 2D programme, then we would laser-cut these shapes in paper and do many alterations [iterations?]. Then we would go into a harder material, like a plastic.

Once we have the icons, then we got it into 3D. And then 3D print that. Then we got into laser-cutting metals. So it is a long, intricate, back-and-forth process.

James Pallister: So it was quite a manual process? It wasn't so much using models and computers?

Isabelle Olsson: Yes. What looks good on the computer doesn't necessarily translate, especially with something that goes on your face. So as soon as you have an idea, you need to prototype it to see what is broken about it. You can then see what looks weird. It can be completely off - too big or too nerdy and you look crazy! It can be a case of a couple of millimetres.

The next stage is about trying it on a couple of people too because something like this needs to fit a wide range of people. That is what I think is most exciting is that everyone on our team uses Glass. We gave them prototypes early on. It was interesting to get feedback from them and it was also valuable for me to see people walking around with them everyday.

James Pallister: What do people pay to get the device?

Isabelle Olsson: So the Explorer edition [the version of Glass released last year] is now $1500 then this new prescription glasses accessory is going to be $225.

James Pallister: Did you have to build different software to cope with the curvature of the lens?

Isabelle Olsson: No, it just works for the regular device. What's great about it is that our existing Explorers can buy the accessory, which is just the frame part, and then attach it to their device.

James Pallister: How long do you think it will be before wearing Google Glass becomes a normal, everyday thing? Five years? Ten years?

Isabelle Olsson: Much sooner than 10 years I would say. The technology keeps on evolving. That's the critical part about the Explorer programme [the early adopters who have been given access to Glass], to get people out in the world using Glass in their daily lives. Once more people have it, people are going to get used to it faster.

Even with the original edition or the base frame, after half an hour people say that they forget they are wearing it. When you put it on, it is so lightweight; you can personally forget that you are wearing it. Then it is about other people around you getting used to it. It takes maybe three times that amount for that to happen.

James Pallister: Have you heard of any unexpected uses of Glass?

Isabelle Olsson: I mean personally I was hoping for these cases so when anything comes up I am more excited than surprised. The artistic use of it appeals to me as a designer, when people use it to make cool stop-motion videos or in other arts projects. But also there is this firefighter who developed this special app so he can see the floorplan of a building, so it could help save lives. The more people I see using it, the more exciting it gets and the more diverse it becomes.

James Pallister: Some people are predicting that wearable technology is just a stepping stone towards cyborg technology, where the information is fed directly into the brain. What do you think of that notion?

Isabelle Olsson: I think the team and myself are more interested in what we can do today and in the next couple of years, because that is going to have an impact and be really amazing. You can speculate about the future but somehow it never ends up being what you thought it would be anyway. When you see old futuristic movies, it is kind of laughable.

James Pallister: It seems that we are getting closer and closer to a situation where we can record every situation. Does that ever worry you from a privacy viewpoint?

Isabelle Olsson: I think with any new technology you need to develop an etiquette to using it. When phones started having cameras on them people freaked out about it.

Part of the Explorer programme is that we want to hear how Glass is working and when it is useful and in what instances do you use it. We are also interested in the social side, how people react when you are wearing it. What are peoples concerns, fears, issues and hopes for it.

We hope that Glass will help people to interact with the world around them, really quickly process information and move on to the conversation they were having.

James Pallister: What do you think is the next stage for Glass?

Isabelle Olsson: Tight now we are definitely focused on slowly growing the Explorer programme, making sure that people get these frames in their hands - or on their faces should we say. We are really excited about that and obviously we are working on prioritising feedback and also creating next generation products that I can't talk about!

James Pallister: Are there any types of technology that you think Glass will feed into in the future?

Isabelle Olsson: I think a lot of things. It is hard for us to speculate without revealing things but the focus is to make technology a more natural part of you and I think any type of services that does that. Glass is going to feed that.