Dezeen remembers Pritzker Prize laureate Hans Hollein, who passed away last week at the age of 80, with some of the best projects from his career spanning almost five decades (+ slideshow).

Viennese architect Hollein, who died just weeks after his 80th birthday, was one of the leading exponents of Postmodern design in Europe. His work is often featured in the teaching syllabus at leading architecture schools and earned him the Pritzker Prize, architecture's equivalent to the Nobel, in 1985.

"Hans Hollein has been a friend and inspiration," said London architect Zaha Hadid, who paid tribute to Hollein on his birthday.

"I first became familiar with his work as a 4th year student in 1976 when I visited Vienna. I admired his conceptual originality as well as his exquisite drawings and designs. His idea of the crack impressed me and led me to the ideas of fragmentation, explosion etc. A true innovator of the discipline in a time when architecture had to radically reinvent itself."

Born in Vienna, Austria, in 1935, Hollein graduated from the city's School of Fine Art in 1956. He moved to America to complete his postgraduate studies with a Commonwealth Fund Scholarship. He would later state that America had a "profound effect" on him.

"Not only have I studied in this country, but more important to me were the people and the spirit of this country, its wide expanses and its persuasive landscape that have played a major role in the formulation of my thoughts and attitudes about architecture," said Hollein.

He returned to Vienna to launch his own practice as a certified civil engineer in 1964. The first commission to earn him international attention was tiny: a 14.8 square-metre shop and showroom for candle retailer Retti. This project, with its graphic aluminium frontage and striking mirrored interior, won Hollein the $25,000 Reynolds Memorial Award – a prize worth more than the project's total budget.

This was quickly followed by his first American project – the Richard Feigen Gallery in New York, which completed in 1969 – and a series of similar commissions. Among the most significant of these was Jewellery Store Schullin I, the first of two branches he designed for the same client in Vienna. He also established a reputation for his experimental conceptual work, including collages and drawings.

"The visionary architects have always straddled the hazy line between sculpture and architecture," said gallerist and art collector Richard Feigen. "Hans Hollein is certainly one of the visionaries of the 20th century, and as such was central to my 'Visionary Architecture' exhibition of some fifty years ago. Alas, like much of Hollein's work, the facade of the gallery he designed for me in 1968 has been destroyed."

Dezeen columnist and former director of architecture firm FAT Sam Jacob, was in Vienna when news of Hollein's death broke.

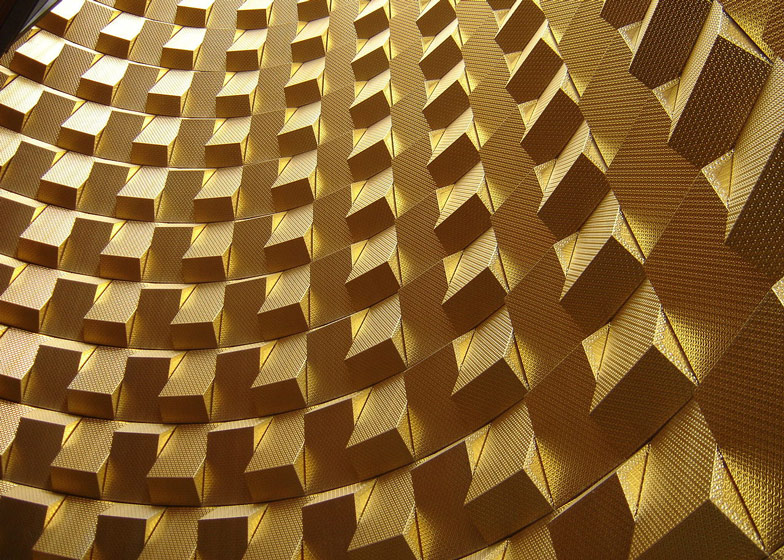

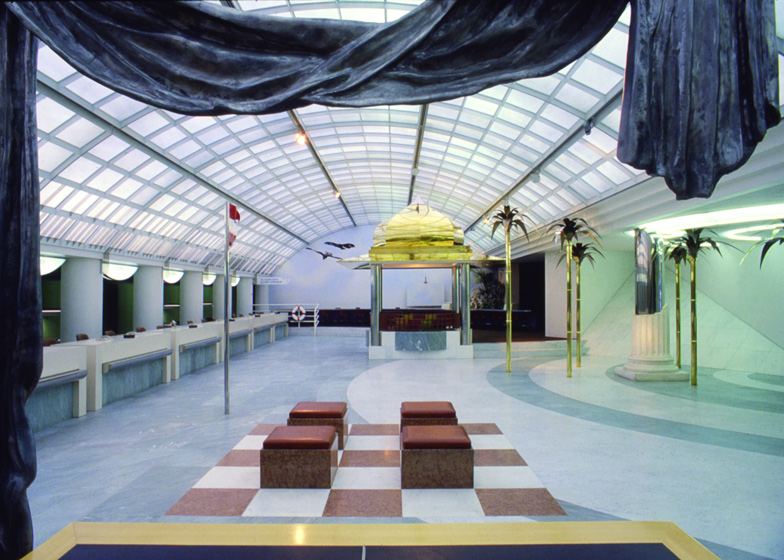

"I was talking about my own work and couldn't help think of the impact Hans Hollein's early work had on me," he said. "There were the images of aircraft carriers stranded in the landscape – a darker, more menacing version of Archigram's Walking City, his Strada Novissima that comically and profoundly told a narrative around the history of the column, and the sublime interior for Österreichisches Verkehrsbüro with its grove of golden palm trees."

"With these kinds of projects Hollein seemed to channel a Viennese culture that merged Freud's unconscious with Loo's mystery and polemic. What these projects seemed to say was that architecture was far more than building – or as he put it so succinctly 'alles ist architecture'."

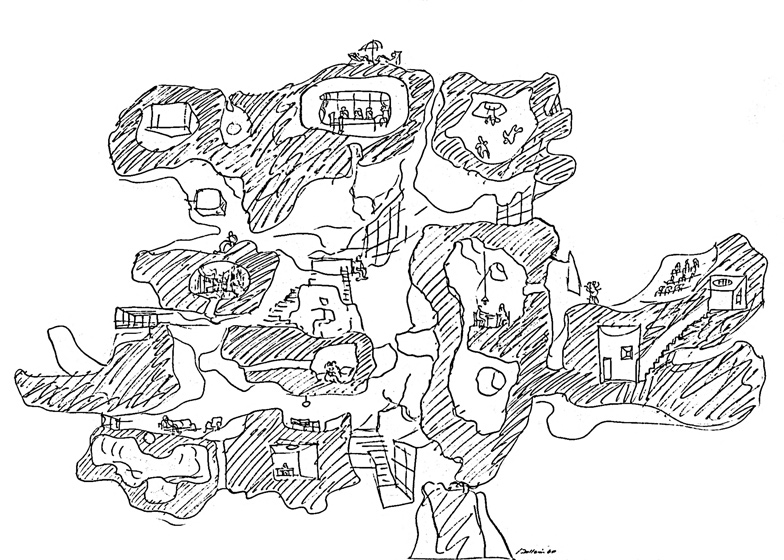

One of Hollein's best-known major public commissions came in 1972 with Museum Abteiberg. The modern art museum in the German town of Monchengladbach was designed to respond to its historic setting adjacent to a cathedral and abbey, and built into a sloping site. It was completed two years before Hollein was given the Pritzker Prize.

"I approached the matter of planning this museum both as an architect and as an artist," said Hollein. "Flexibility here does not imply mobile ceilings and wall elements but rather, a spectrum of multilayered situations that are revealed in relation to the work of art, and to which the work of art responds. The responsibility of the architect is not transferred to the curator's shoulders. The architect creates an independent work of art – for other works of art and for human beings."

Before the museum was completed, Hollein had already finished a string of other cultural projects across Europe, as well as the Museum for Glass and Ceramics in Tehran. These projects, as well as a reputation as an inspiring teacher, helped land him the Pritzker, where the jury honored him as a"true master – one who with wit and eclectic gusto draws upon the traditions of the New World as readily as upon those of the Old."

"He mingles bold shapes and colours with an exquisite refinement of detail and never fears to bring together the richest of ancient marbles and the latest in plastics," said the citation.

Abteiberg heralded a new phase in his career, with bigger and higher profile projects and clients, including the Frankfurt Museum of Modern Art, known as the "slice of cake" thanks to its triangular shape.

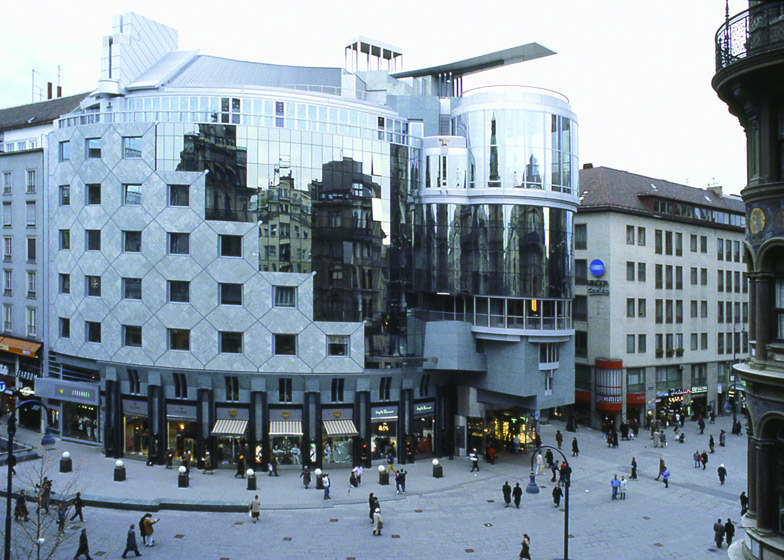

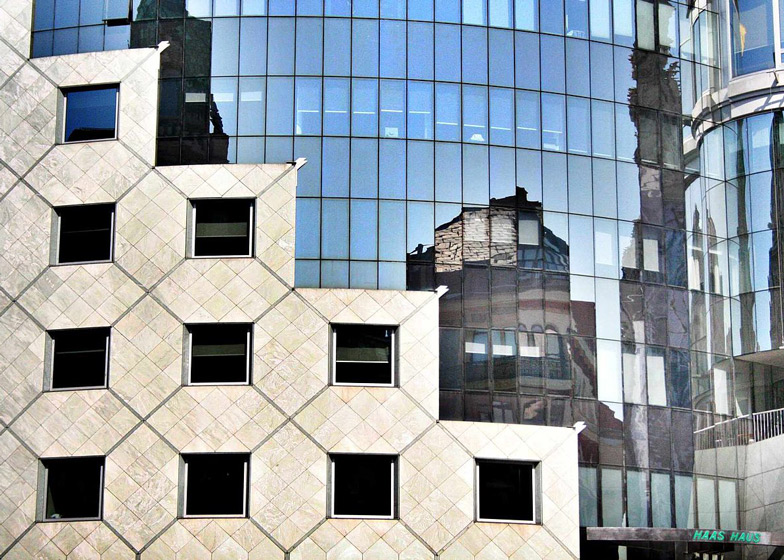

One of his most controversial structures is from this period – the Haas House, a commercial building in Vienna opposite St Stephan's Cathedral, whose form echoed the shape of the Roman fort which once stood on the site. With large mirrored glass sections across the facade, a corner of the building was designed to cantilever out over a subway station, creating an effective divide between two public spaces. It is regularly criticised for jarring with Vienna's traditional architectural style.

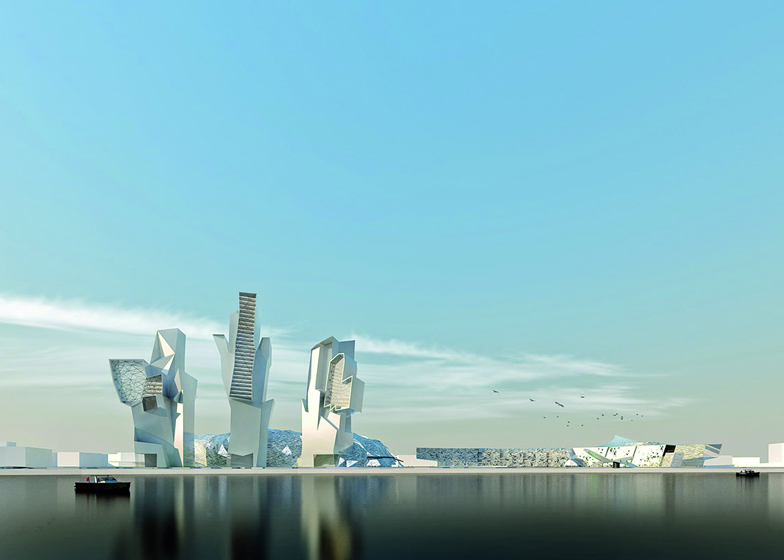

A spectacular, competition winning design for an underground gallery to house the Guggenheim in Salzburg was never built.

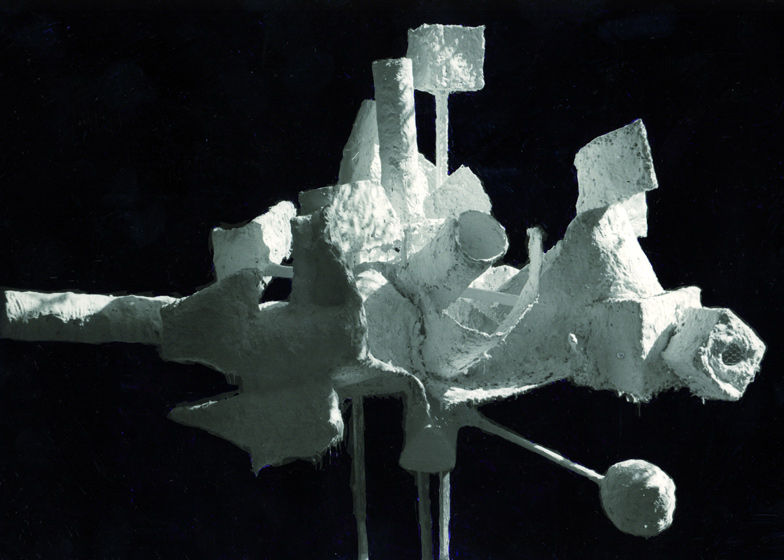

Despite being repeatedly commissioned to create big, bombastic buildings, Hollein remained interested in small projects throughout his career and enjoyed playing with scale, designing lamps, jewellery, glasses, tableware and furniture as well as exhibitions.

"When the projects reached a certain scale and civic importance, Hollein's lack of interest in behaving overwhelmed them," said critic Aaron Betsky in Architect Magazine. "Architecture as a form of analysis, a gesture, an elaboration, a juxtaposition of elements, a reversal of scale or material – this architecture was his forte."

His experiments in product design included a tea set for Alessi, which allowed him to develop earlier concepts for an aircraft carrier into functional pieces of tableware. He also created the exhibition design for MANtransFORMS – the inaugural exhibition for the Cooper Hewitt Museum in New York – and was director of the Venice Architecture Biennale in 1996.

"I have always considered architecture as an art," said Hollein. "To me architecture is not primarily the solution of a problem, but the making of a statement.

"Not only do I deal with eternity, with the permanent, but also with the ephemeral and the temporary. As an artist, I am only responsible to myself and can make highly individualistic manifestations. As an architect, I am responsible to the needs of man and society. Man continuously designs for survival, for immediate survival and for survival after death. The life and work of an artist and architect mirrors this fundamental human situation."

A major retrospective of Hollein's work is currently on show at the Abteiberg Museum and finishes in September.