Feature: the first branch of Habitat opened its doors 50 years ago today, changing the British public's relationship with furniture and homeware forever. But can the shop that brought flat-pack furniture, the duvet and the wok to the UK make a come back, asks Dezeen editor Anna Winston (+ slideshow).

Designer Terence Conran had dropped out of London's Central School of Art and Design in the late 1940s at the age of 19 to work for architect Dennis Lennon, before setting up his own business, Conran & Company, in a Notting Hill basement in 1952. He began making a range flat-pack furniture – which he claims was the first of its kind in Britain – but quickly came to the conclusion that retailers didn't know how to promote it properly.

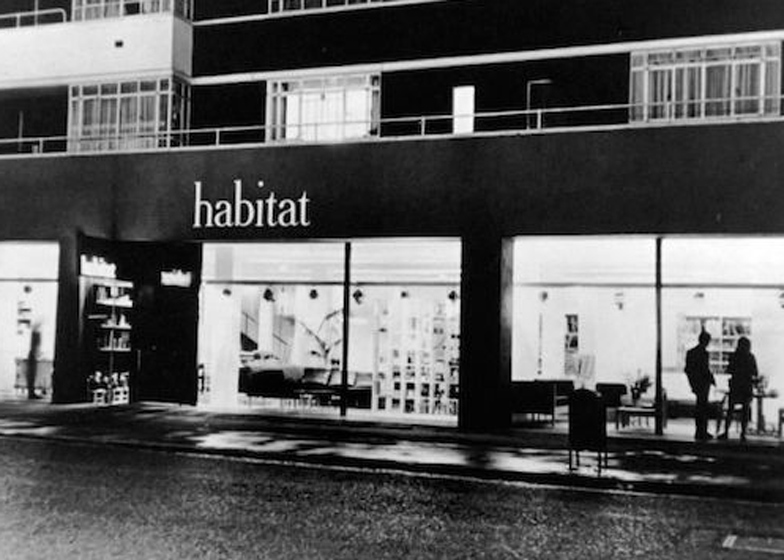

It was this frustration that led, eventually, to the opening of Habitat on London's Fulham Road on 11 May 1964.

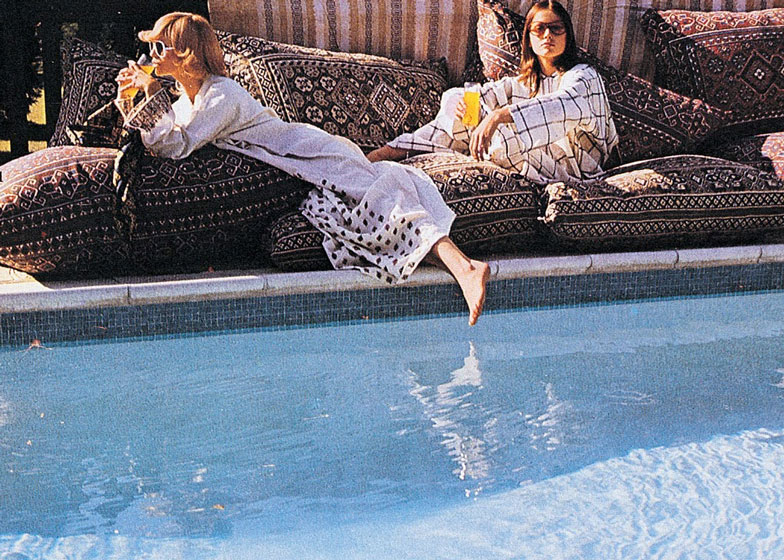

The timing was perfect. Conran and his partners expected the shop to appeal to a relatively minority market, but they had underestimated the appetite for a new way to express personality and taste through fashion and homewares in a generation that was throwing off the shackles of war and rationing.

"In 1964 Habitat was at its most influential – it was a revolutionary new way of looking at retail and homeware," says British designer Tom Dixon, who was appointed head of design at Habitat in 1998 and worked for the company until 2008. "When Terence Conran was completely involved in a single shop it was an iconoclastic blast of fresh air in a monochromatic and still very conservative Britain still in slow recovery from a devastating war."

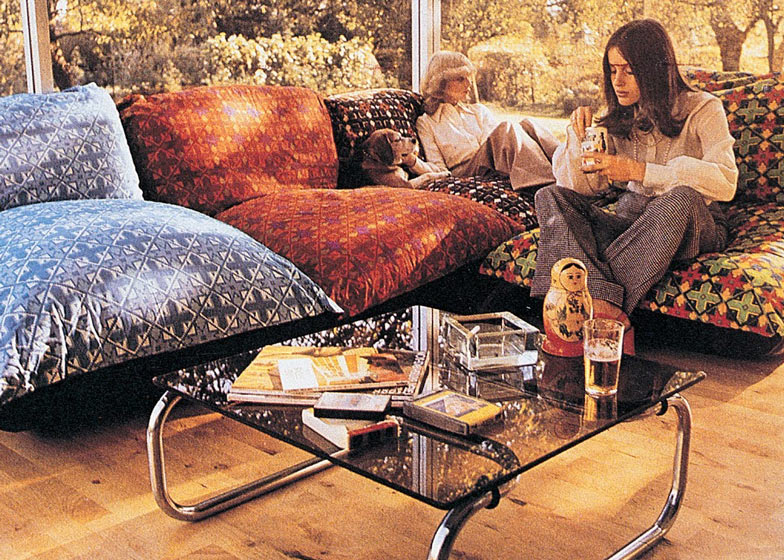

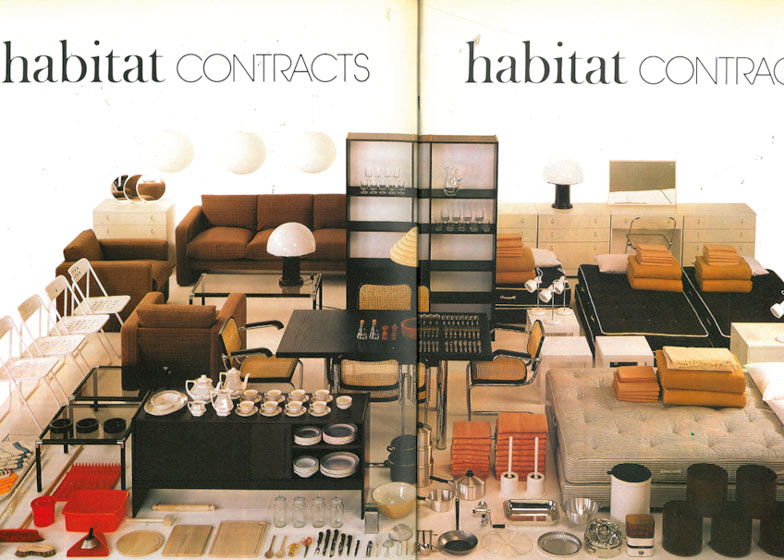

Alongside Conran's own collection were 2,000 other pieces of furniture, fabrics, lighting, kitchenware, glass and carpets, sourced from Britain, France, Italy and Scandinavia and selected by a design panel. Products were chosen to appeal to "young moderns with lively tastes" and priced accordingly, mixing traditional pieces with new Modernist-influenced designs.

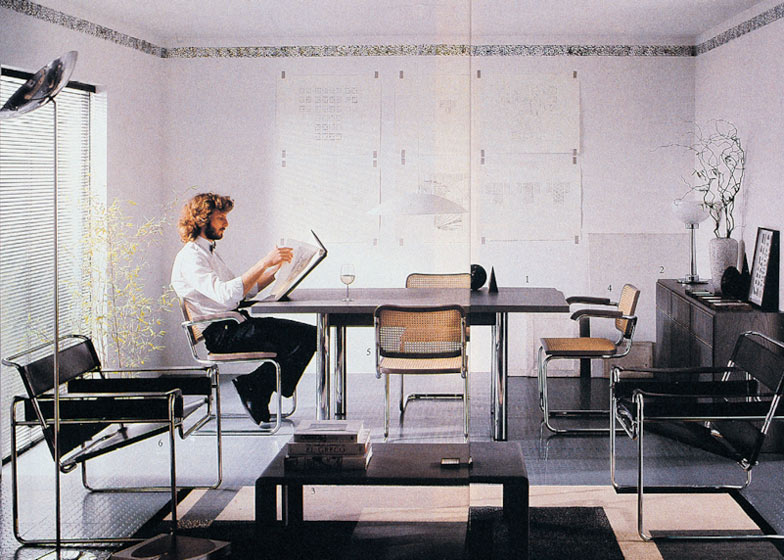

The quarry-tiled floors, whitewashed brick walls and slatted wooden ceilings of the first store created a spacious lifestyle setting with spot-lit products and would become a template for the chain of stores that followed. A second branch opened on London's Tottenham Court Road in 1966, and another six were to follow over a three-year period, as well as a mail-order business.

"Habitat brought well-designed items into peoples homes before they knew what design was," explains former head of the Royal College of Art's Design Products programme Tord Boontje, whose laser-cut Garland light was Habitat's best-selling product in 2003. "It made functional, beautiful, well-made furniture, textiles and tableware affordable and accessible to many people. I think it set a benchmark and made other retailers modernise and focus on affordability and quality."

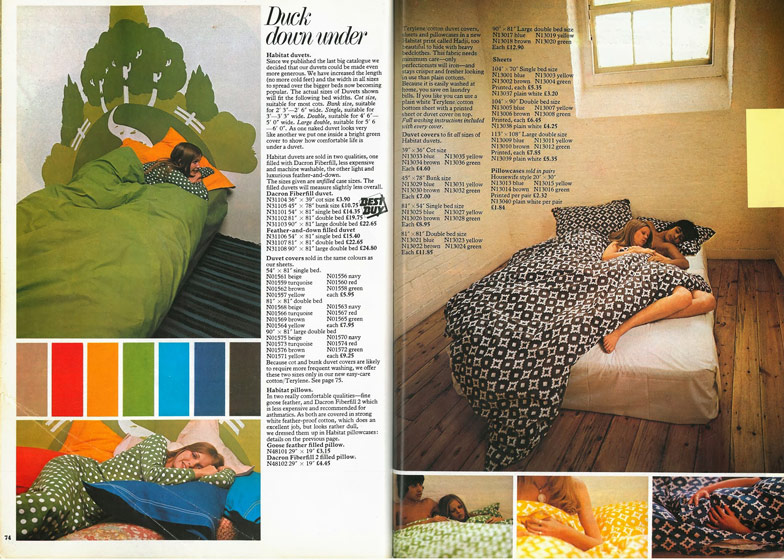

By 1980, Habitat was one of the world's biggest furniture retailers, with 47 stores globally. It was responsible for introducing Britain to designers that have become household names and products that have become ubiquitous, including the wok (which came with an instruction manual explaining how to use it) and the Continental Quilt – now better know as the duvet – which Conran brought in after sleeping under one in Sweden. Habitat sold chairs by Charles and Ray Eames, and Robin Day, alongside prints of newly commissioned works by artists including David Hockney and Eduardo Paolozzi.

Habitat was a deeply personal project for Conran and his team, with his own living room appearing in the first catalogue and the managing director's cat making regular appearances in subsequent editions.

In-store displays were styled to look like the kind of ideal home that would encourage customers to buy into a lifestyle involving multiple purchases. This approach to in-house marketing would quickly catch on and become one of the hallmarks of a newcomer that would challenge Habitat's unrivalled rule over the affordable end of the market.

Habitat's first sticky patch came with the arrival of Ikea in 1987. This coincided with the onset of a recession and rising prices on Habitat products, a bad combination made worse by the loss of Conran, who was forced out in the early 1990s by internal politics after merging Habitat with other British retail giants Mothercare and British Home Stores to form the Storehouse Group.

"Ikea wasn't just another retailer, its aim was to completely transform British attitudes to design," says London Design Museum director Deyan Sudjic in his latest book B is for Bauhaus.

"Despite Habitat's high profile success in the 1970s, the vast majority in Britain still took the view that modern design was a piece of chilly good taste of the kind that the well-bred attempted to inflict on those less fortunate than themselves," says Sudjic.

"When they had the chance to choose for themselves, the vast majority of the population looked in the opposite direction."

Habitat was bought by Ikea in 1992, but although the Swedish furniture giant was enjoying massive growth with its own shops, it struggled with Habitat.

In 1998, it appeared to have hit pay dirt with Tom Dixon, one of the biggest names in British design. Dixon, who lasted 10 years as Habitat's design director, brought in a new generation of designers and products. But despite a revival of public interest, it wasn't enough.

According to retail industry magazine Retail Week, Habitat has only made two annual profits since 2001. In 2009, Habitat's 71 stores and 1,500 staff contracts were sold to private equity firm Hilco, who eventually entered the remaining branches into administration leaving just three London stores and an online sales business.

"Habitat produces things of higher quality and consideration than Ikea but more affordable than Heal's and Selfridges: I think there's a lot of us who sit in that bracket," says designer William Warren, who is senior lecturer on furniture design at London Metropolitan University's Sir John Cass faculty of art, architecture and design.

"But the reality of selling furniture from a screen image is hard. No matter how close in we can zoom or rotate virtual furniture nothing beats sitting in a chair, smelling a leather, hearing a cupboard door close or feeling the weight or finish of a object. Habitat still has my trust in terms of quality but I don't think I'd spend big money online without some real first hand experience first."

Habitat's current owner Home Retail Group (HRG) bought the remains of the UK business in 2011. HRG is the owner of two of Britain's biggest DIY and self-service retailers, Homebase and Argos, and there are now mini-Habitats and Habitat product lines in a number of these shops.

Elle Decoration editor Michelle Ogundehin declared the brand "as good as dead" in November 2011, giving it just two years to die out completely. But one of HRGs first moves was to bring in a respected creative director in Polly Dickens, formerly of the Conran Shop.

In an interview with Dezeen following her appointment in 2012, Dickens said she was taking the brand "back to what Habitat was many years ago in the original Conran days, when people thought about it as colourful, good design and something that had a very strong personality."

Production has been moved back to Europe and design brought back in-house as much as possible. With a strong focus on affordability, Dickens now believes the brand can once again hold its own as long as it has "the right supplier base."

"It is important that as a team we design into the price and the design team here works very closely with our buyers and the specific skills of given factories to achieve the competitive price points we have today," says Dickens.

But not everyone is convinced.

"It will struggle in the contemporary landscape where there is constantly increasing competition from fashion brands like Zara getting interested, American giants like Anthropologie and CB2 coming over and the global monsters like IKEA dominating," says Tom Dixon.

"Habitat is now also split into a UK operation with a different ownership to the rest of the world which makes little sense in a world with fewer borders, and this will give them problems with scale."

Despite some misgivings, there is still a lot of goodwill and affection felt by designers and collectors towards Habitat.

In February this year, the branch on Tottenham Court Road that originally opened in 1965 was named one of London's top 100 shops by city guide magazine Time Out.

It remains an instantly recognisable brand name in the UK and, even as new homeware stores arrive on the British high street, some feel that there is a niche to fill.

"When I meet people on a train journey or at a garden party and they ask what I do, they always understand and have that recognition when I say that I have designed a light for Habitat," says Tord Boontje.

"There is a real need for original, beautiful, creative, functional and affordable products of a good quality. This is an unfulfilled role: there are some retailers with affordable products but dubious quality; there are those with good quality but not affordable; and then there are those that just sell boring and stupid stuff," he adds.

"I think that Polly Dickens as creative director understands that Habitat is in a unique position to get all these ingredients right. She is transforming Habitat through design into a very exciting retailer again."

All images courtesy of Habitat. Additional reporting by Dan Howarth and Matt Hussey.