Virtual reality headsets create "pastoral" illusion for battery-farmed chickens

Battery-farmed chickens could be tricked into thinking they are roaming free if dressed in virtual reality headsets designed as a tongue-in-cheek proposal by US company Second Livestock (+ interview).

"Following the trend for humanity to live in an ever more virtual and augmented reality, we offer animals the same sense of safe freedom," reads the Second Livestock website.

The company's Virtual Free Range programme is a tongue-in-cheek reaction to the hype surrounding virtual reality. It uses the technology yo respond to concerns about animal welfare by creating a virtual world for chickens, an animal the project's creator Austin Stewart calls the "poster child for really poor living conditions on farms".

The artist came up with the idea for Second Livestock when one of his art professors at Ohio State University said that there was evidence to suggest that free-range chickens are more vulnerable to stress as their conditions are less controlled, even though giving them access to the outdoors is felt to be more humane.

"I thought, what if we could give them a really safe, comfortable life in the cage, but the ability to range freely in a virtual world?" he said.

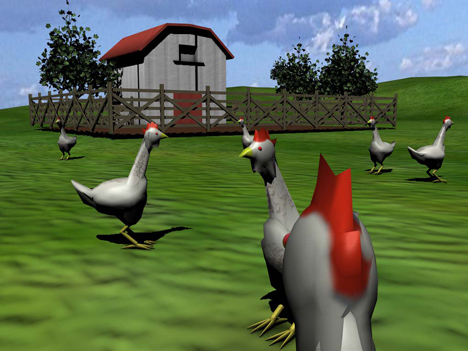

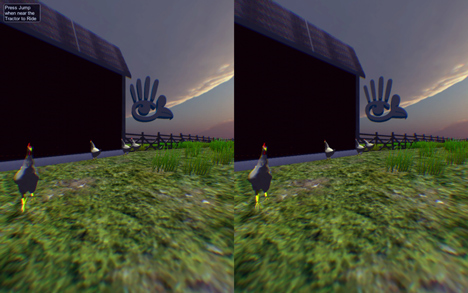

Stewart has created a demo for humans to experience what the virtual world would be like, using an Oculus Rift headset paired with a ball for hands to walk on as feet. "There's a farm, there's a tractor, there's a fence," he described. "It looks really pastoral."

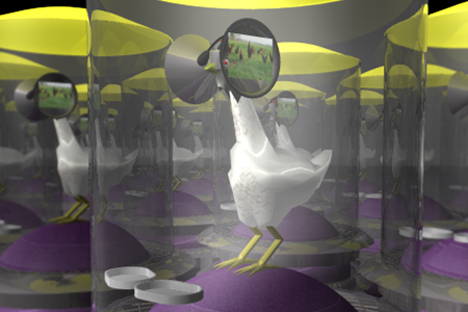

If built for a chicken, the headset would have to be adapted for the birds' 300-degree field of view and ability to see near-ultra-violet light.

"You could really build this and put a chicken in it, we have the technology to do that," said Stewart. "It's a little bit too expensive at this point to make it practical, but in 10 years I could see this actually being a reality."

The chickens would walk around on a ball that rolled to counteract their movements. They could also peck at grubs, which would be translated as real food on a sensor-controlled tray that follows the bird's beak around the small space it occupies.

Animals in the same factory would be able to see each other in the virtual environment and communicate with each other via microphones attached to the headsets.

"Any of the chickens wearing these headsets would be networked together so they can all socialise in the virtual world," said Stewart.

His ideas for the future include virtual realities for neglected pets and depressed zoo animals. "All these works are meant to be this point of conversation that anyone can engage in," he said. "You don't have to have some greater understanding of the history of art in order to engage with this work."

Here's the transcript of our conversation with the creator of the spoof company, Austin Stewart:

Dan Howarth: Could tell me about how you came to propose virtual reality for chickens?

Austin Stewart: I was sitting in a lecture by Michael Mercil — a professor of art at Ohio State University — who does a lot of work with animal husbandry and the relationship between farmers and their animals. Somebody after the lecture was asking him some pretty aggressive questions about why he wasn't pushing for animal rights or free-range chickens versus congenitally farmed chickens. He said: "well free range chickens happen to have more injuries and these other signs that they've had a stressful life, while these other chickens don't. Which is better, the more stressful outdoor life or the indoor life. Who's to say?" I thought: "what if we could give them a really safe, comfortable life in the cage, but the ability to range freely in a virtual world?" So that's where the idea was born.

With all of the work that I do, I try not to take a particular stance but to open up a conversation and bring it into a public forum. Take it out of academic circles or the art world or whatever, and present it in a way – obviously in this case with humour – and make it probable.

You could really build this and put a chicken in it, we have the technology to do that. It's little bit too expensive at this point to make it practical, but in 10 years I could see this actually being a reality. Especially as the world changes and our population continues to grow. So all these works are meant to be this point of conversation that anyone can engage in. You don't have to have some greater understanding of the history of art in order to engage with this work.

Dan Howarth: What would the virtual world for the chicken be like, what would they see in the headset?

Austin Stewart: In the fully functional demo it's more meant for humans. So there's a farm, there's a tractor, there's a fence. It looks really pastoral. But chickens... there aren't really any wild chickens. Whatever species they came from is completely gone, so there's no way to know what a truly wild chicken would want. Chickens do prefer to roost in trees and they like a mix of open grassland and some forest areas with cover. That would be what the new world looked like; totally open, they could go anywhere they wanted to.

Any of the chickens wearing these headsets would be networked together so they can all socialise in the virtual world. Then there would also be bugs and things, crawling around the world that chickens could peck. By knowing where their head is with the sensor, the food trays can be rotated to the perfect position so when they peck they actually get food, or scratch, or water as well.

Dan Howarth: So the shape of the device is tailored to the chicken's eyesight, which is completely different to ours, as their eyes are on the side of the head?

Austin Stewart: Their field of view is 300 degrees and they have a very small area where they actually have binocular, stereoscopic vision. So that's why the headset was designed like that.

There's another thing about their eyes, which is something we'd have to work on if this technology was actually to be developed. As we see red, green and blue, they also have a tone in their eye that allows them to see violet or near ultra-violet, so we'd need to develop an LCD screen that actually had that fourth colour in each pixel. And probably a camera so we could observe what that looks like and make those markings in the virtual world for the chicken. That's a huge part of getting food, mating and doing all the chicken things they do.

Dan Howarth: There's a microphone attached to the headset as well that picks up noises. Can they talk to each other?

Austin Stewart: Yes, absolutely, so that they can fully socialise with one another. I do the presentation in this real TED-style or corporate sales pitch—polished. Horrifying. Then I have a Q&A period and a lot of the time people often ask "well how do you touch or smell?" I usually say: "that's the next step. We've conquered vision and mono and now we're working on touch, maybe using precisely timed blasts of pressure to give them the sensation of touch."

Dan Howarth: Would you want to extend the project to other types of animals as well? Cattle are sometimes kept in farms in a similar way.

Austin Stewart: As part of the presentation, at the end, I sound really excited about the couple of new projects we're working on. One is Second Dog Park and the other is Second Habitat. Second Dog Park is a virtual reality for your neglected pets and Second Habitat is a virtual world for depressed zoo animals. That is the future of Second Livestock: to go further, to more species. Part of this project was building this physical treadmill and the parts so people can see this is an actual thing; it's not just 3D-rendered images and a concept.

The chicken was the perfect sized animal to start with and they're also this kind of poster child for really poor living conditions on farms. The other thing is that when you're seated in front of this treadmill, and you put you hands on this ball, from the hands – which are basically the feet of the chicken – to the head, you're about the size of a chicken. It gives that person a really good chicken experience because you get to wander around the world as though you're a chicken. Making something for a cow would just be so expensive and putting a human in there would probably be dangerous. So chickens were the best kind of animal, symbolically and practically.