Venice Architecture Biennale 2014: experimental architecture from the 1970s, from names including Toyo Ito, Tadao Ando and Riken Yamamoto, is presented on a makeshift construction site inside the Japanese Pavilion (+ slideshow).

Following the Golden Lion-winning installation of 2012, which showed concepts for post-tsunami housing, Japan's 2014 pavilion exhibition looks retrospectively at projects that emerged after World War II and helped to shape the country's modernisation.

Entitled The Real World, the show aims to capture the spirit of a period where young Japanese architects drew inspiration from communities across Asia, the Middle East and Africa, and came up with radical concepts for urban living.

The resultant projects varied from Hiroshi Hara's Umeda Sky Building, where two towers are connected by a bridge to create an elevated village, to the simple concrete Row House by Tadao Ando, which set the precedent for many of today's city dwellings in Japan.

Other projects featured include Takashi Hasegawa's revisit to styles from the Taisho period, as well as Osamu Ishiyama's design for a house within a huge corrugated pipe.

The exhibition was put together by curator Norihito Nakatani. Research involved interviewing architects, historians, artists, photographers and writers to gather a broad view of the ideals of this period.

"During the 1970s in Japan, professionals of all kinds questioned the consequences of modernisation and tried to understand what was happening in the real world," she said. "We believe their efforts created the fertile ground that produced the flourishing condition of Japanese architecture today."

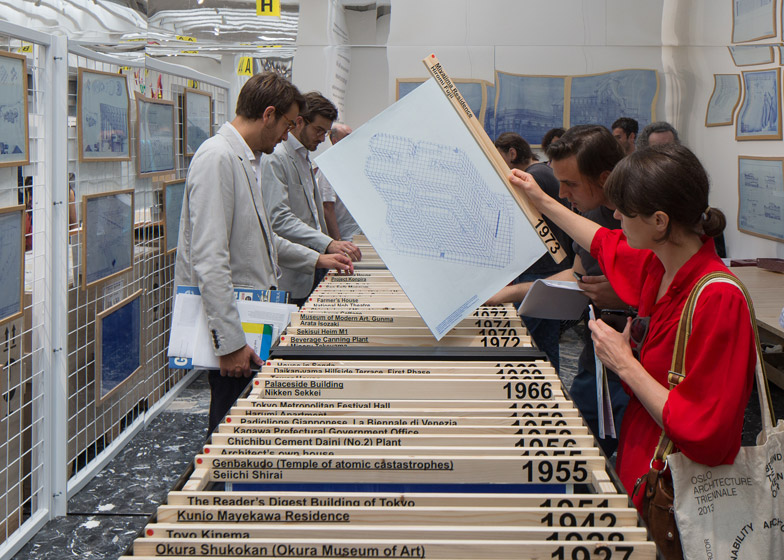

A bright red arrow marks the entrance to the exhibition. Inside, a viewing platform offers visitors an overview of the models and artefacts on show, while a printer tucked in the corner provides an opportunity to produce blueprints.

The Japanese Pavilion is one of 28 national pavilions located in the Giardini of the Venice biennale. Others include the Korean Pavilion, which was awarded the Golden Lion, and the Belgian Pavilion, which celebrates common domestic architecture.

Follow Dezeen's coverage of the Venice Architecture Pavilion »

Here's a statement from the exhibition team:

In the Real World

Modernisation in Japan began with the import of Western civilisation and progressed at a ferocious pace. After a rapid recovery following the country's destruction in World War II, Japan rose to become the world's second largest economy in 1968. Architecture was instrumental in this modernisation, which reached its climax at the Osaka Expo '70.

Yet almost simultaneously, the country was confronted with a host of problems, most notably environmental pollution, stagnation of living conditions, and the oil crisis, making it seems as if modernisation had reached an impasse. This critical situation triggered a thorough reexamination of modernism in Japanese architecture, and in turn prompted a variety of independent reactions.

The young architects who arrived after the Modernists reconsidered their roles as professionals and undertook bold experiments with small houses to suggest a new vision of the city. Some of theme embarked for other parts of Asia, the Middle East, and Africa to study how communities are formed. And historical researchers and urban observers left their offices with their cameras and notebooks in hand to map out the real city and history in a fight against oblivion and oppression. Some of these activities became works of art, and many earned support from the publishing world and enlivened the architectural media.

The reexamination of modernism in Japanese architecture lies in the synergy of these activities of the 1970s. Ultimately, they were desperate efforts to redefine architecture by learning from life in the real world.

It is important to note that these efforts were not limited to small-scale, peripheral experiments. This generation's ambitious vision actually opened up a window in the generic skyline of the city. For the record, Umeda Sky Building consists of two high-rise buildings connected by a bridge. The design, an attempt to create a village in the city, was informed by the architect's research of ancient communities in other parts of the world. The transcendent proposal convinced the client and the construction firm to go for it.

Uniform as it seems, contemporary architecture is actually a culmination of countless experiments. In fact, any society can give birth to a great work of architecture provided it has the will and a good idea. In this exhibition, we will unearth architectural projects and historical perspectives that emerged in Japan in the 1970s along with a variety of artefacts collected from the last 100 years. By delving into the issues suggested by these endeavours, we will demonstrate the essential power of architecture and present suggestions for our lives today.