Cedric Price is "like Marcel Duchamp" says Hans Ulrich Obrist

Venice Architecture Biennale 2014: the late English architect Cedric Price is "one of the most important figures in all disciplines in the 20th century" and comparable to Marcel Duchamp in terms of his influence, according to curator Hans Ulrich Obrist (+ interview + slideshow).

"He's like Marcel Duchamp, he's really a key figure," said Obrist, who is co-director of exhibitions at the Serpentine Gallery in London. "And I think it all comes together in the Fun Palace, which for me is one of the most important projects of the 20th century."

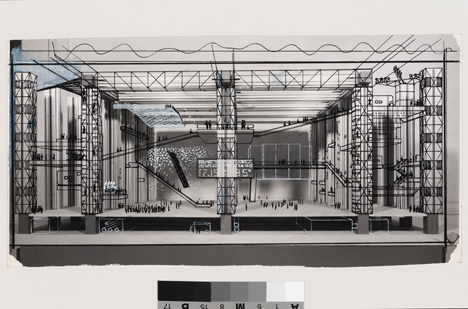

The Fun Palace was an unbuilt 1961 design for a flexible, open-plan structure that heavily influenced Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano's Pompidou Centre in Paris.

It is celebrated in the Swiss Pavilion – titled A Stroll Through A Fun Palace – at the Venice Architecture Biennale, which Obrist has curated and which explores the work of both Price and Swiss sociologist Lucius Burckhardt.

Obrist described the Swiss Pavilion as "basically a sketch of the Fun Palace. You know there isn't a prescribed program, you can change it at any moment, anything can be plugged in."

The pavilion, developed in conjunction with Swiss architects Herzog & de Meuron, features material from the archives of both Price and Burckhardt that is wheeled out on trolleys rather than displayed in a traditional exhibition format.

"If you look at the Fun Palace, he anticipated the whole idea of the internet, the idea of participation, of feedback loops, it's all there and it was basically his idea," said Obrist, who is widely regarded as one of the most influential figures in the art world.

Price, who was born in 1934 and died in 2003, built relatively few buildings but influenced a whole generation of architects through unbuilt concepts such as the Potteries Think Belt, a proposal for a decentralised, mobile university campus. The British Pavilion at this year's biennale also featured work by Price.

Visitors to the Swiss Pavilion walk through the structure's main space, which is painted white, and watch a series of activities unfurl. Blinds on the windows that surround the roof open and close as a student wheels out a trolley carrying a projector that shows films and images on the wall, while more students move the trolleys containing archive material around the space.

Work on display also included contributions by architects and artists such as Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, Philippe Parreno, Asad Raza and Tino Sehgal. Atelir Bow-Wow created a graphic installation to sit above the entrance to the pavilion.

A series of back-to-back talks took place during the opening week, with speakers including Atelier Bow-Wow, Herzog & de Meuron, Rem Koolhaas and Stefano Boeri.

Obrist says he conceived the unconventional exhibition because "it's very difficult to show architecture; it always feels very dirty if one has models and drawings on the wall."

This is the reason the Serpentine Gallery launched its series of annual summer pavilions, he said: "[Serpentine Gallery director] Julia Peyton Jones' visionary invention in 2000 was that she said 'if you want to show architecture, you've got to build it!'"

Follow Dezeen's coverage of the Venice Architecture Biennale »

Photography is by Andrea Avezzù unless otherwise stated. Here's an edited transcript of the interview with Obrist:

Marcus Fairs: Tell us about the Swiss Pavilion.

Hans Ulrich Obrist: The Swiss Pavilion is a homage to Lucius Burckhardt, a swiss sociologist, landscape architect and theoretician, and Cedric Price, the English urbanist and architect. Two visionaries who are no longer with us - both died in 2003 - whom I feel need to be remembered and who can be seen together, because both have so much in common in terms of the themes they are interested in, like ecology, environment, networks, they were thinking very early on about networks, traffic, looking at all these things through an amazing practice of drawing.

I did two solo shows about them in Paris when I was at the museum of modern art there and the more I curated their drawings, the more I saw similarities and I thought one day I should bring them together. It was one of my dreams.

And then the invitation came from the Swiss government to do this pavilion and at the same time Rem Koolhaas announced that the theme of the biennale was Fundamentals, and encouraged the pavilions to do something which revisits modernity and revisits figures from the twentieth century. So I immediately thought "that's the moment!". Because also Lucius Burckhardt is not really known to an international audience outside the architecture world and is not so much rated, so it felt urgent to show Lucius, and also to show Cedric here, and celebrate these two.

But obviously the question was, how do you make an archive lively? It's true to say it's an important moment to revisit archives of the twentieth century. It's also got to do with memory, because we have more and more information; we are surrounded by an exponential growth of information, however that does not necessarily mean there is more memory. It might be that amnesia is actually somehow very present in our digital age.

So the idea of memory was there, but how can one do this to avoid that it's just boxes and just presentations of… and particularly it's very difficult to show architecture; it always feels very dirty if one has models and drawings on the wall, which is a reason why we're doing pavilions at the Serpentine. Julia Peyton Jones' visionary invention in 2000 was that she said "if you want to show architecture, you've got to build it!" And she started in 2000 with Zaha Hadid and since 2006 when I joined the Serpentine it's this wonderful experience together that every year we select an architect. It's really unrivalled.

So I was thinking, what are we going to do with an archive? How can we make it lively? And then I was thinking that the best way would be just to bring architects and artists together and develop a performativity of the archive.

So I invited Herzog & de Meuron, who were the first architects I met as a teenager in Switzerland. I had never met an architect before; I was in the art world. And I got to know them and they told me in that first meeting when I was like eighteen or nineteen years old to read Lucius Burckhardt. I remember them telling me that …and they're obviously the students of Burckhardt.

I invited them to design the exhibition and co-curate with us the archive. And they came up with this wonderful idea of the trolleys because when we actually went to the Lucius Burckhard archive we were shown these trolleys, so basically they wheeled them in and out and the idea would be that the trolleys would be this display feature.

As Marcel Duchamp says – and Richard Hamilton often quoted him: "We mainly remember exhibitions which also develop a new display feature".

So Herzog & de Meuron has this idea of the trolleys and I then wanted to invite artists who all have reflected for a long time on the choreography of exhibitions. We wanted to keep the left and the right hand side completely empty so when you arrive in the morning it's like two white cubes.

Marcus Fairs: What is Cedric Price's position in architectural history?

Hans Ulrich Obrist: He's one of the most important figures in all disciplines in the 20th century for me. He's like Marcel Duchamp, he's really a key figure. I've thought about him every day you know since the 90s. For me his ideals; if you think about the Potteries Think Belt as a whole educational unit on the move, re-activating an abandoned railway line to become a school on the move, his classrooms on the move. It's incredibly contemporary and anticipating with his network ideas the age of the internet.

And I think it all comes together in the Fun Palace, which for me is one of the most important projects of the 20th century. We have here the original model from the CCA [Canadian Centre for Architecture]; the whole project is a collaboration with the CCA. If you look at the Fun Palace, he anticipated the whole idea of the internet, the idea of participation, of feedback loops, it's all there and it was basically his idea.

And what we're doing here is basically a sketch of the Fun Palace. You know there isn't a prescribed program, you can change it at any moment, anything can be plugged in. I think you know Cedric's work, I mean these are the very well-known projects: the Fun Palace and the Potteries Think Belt. If one looks at the archive here every day new things come out.

I mean this morning we looked with all the participants and the visitors at The Lung. So one of his last projects was actually to give a lung to a city, so he was invited to a big competition in New York and instead of building, as always, he actually injected an oxygen lung. And if you look at Beijing right now where people can barely breathe, what better project for the 21st century than to inject a lung of oxygen?

So he's just full of sparks and full of ideas and many of his drawings in the archive could have been done today. It's so contemporary.

Marcus Fairs: What do you think of the biennale in general?

Hans Ulrich Obrist: I think it's very exciting with Rem; I think it's really interesting that after so many biennales focussing on the city, where the city was either the main theme or an implicit theme, now this one focusses on the fundamentals. I'm extremely fascinated going through the Central Pavilion that each room sort of zooms back into the past, in the same way he encouraged the pavilions to do. In every room you have the same rule of the game: he visits this amazing German researcher who researched stairs for 50 years. For me it's an amazing discovery. But then he projects it into the future, for example with Tony Fadell [founder of Nest], one of the great inventors of our time.