Jimenez Lai explores domestic cultures of Taiwan with colourful "houses" installation

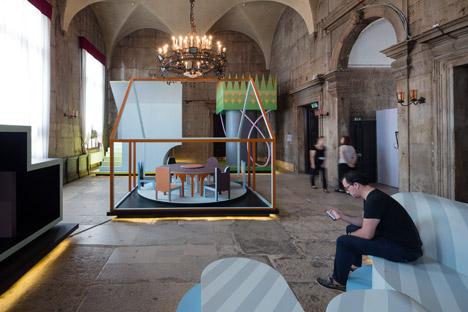

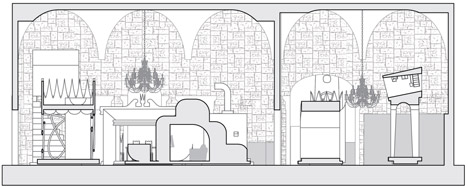

Venice Architecture Biennale 2014: architect Jimenez Lai has filled a Venetian palazzo with nine colourful structures representing different domestic functions, including a House for Pleasure and a House of Shit (+ interview + slideshow).

As a collateral event of the biennale, Township of Domestic Parts: Made in Taiwan is an exhibition that explores the fundamental components of the modern-day Taiwanese home and how these have been shaped by domestic patterns and social activities.

"Once upon a time, even when we became biologically modern, we were living in caves," Jimenez Lai told Dezeen. "We know that naturally we wouldn't shit where we sleep, and we couldn't eat where we crap. So the process of compartmentalisation began a long time ago."

Each of the nine structures addresses a different activity, from sleeping and studying to family dining and lounging. They are presented as clusters of brightly coloured geometric shapes, described by Lai as "superfurnitures".

The central structure is a house-shaped frame that surrounds a circular dining table. "We're looking at the politics of geometry and the Western culture of eating around rectangles, where you can assign power," explained the architect. "But a circle definitely softens the power structure."

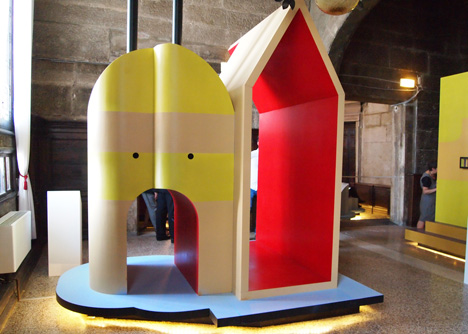

Elsewhere, a boxy yellow structure contains a toilet, described by Lai as "the ultimate fortress of solitude", while the Altar of Appearance and the House of Pleasure describe two different kinds of living room.

"Some people's living rooms are actually used, they sit there in their underwear and watch TV and eat chips," he said. "But some homes also have a living room specifically for the guests. That kind of living room has the best photographs, the best armchair, and is seldom used. It's almost like a vitrine or a shrine of your family."

Small details relate to specific Taiwanese traditions. These include model homes relating to family ancestors, as well as the tradition for open-air banqueting.

Lai and his architecture studio Bureau Spectacular researched the project by investigating 50 iconic houses from architectural history, from Le Corbusier's Villa Savoye to the Eames House.

The exhibition is accompanied by a video of interviews with architects, designers and artists who, like Lai, are either from Taiwan or have been involved in projects there.

Photography is by Iwan Baan, unless otherwise stated.

Follow Dezeen's coverage of the Venice Architecture Biennale »

Scroll down for the transcript of our interview with Jimenez Lai:

Amy Frearson: Can you begin by telling me the main concept of the exhibition?

Jimenez Lai: There are really two aspects to this thing. There is the video component, where I'm actually exhibiting people. I've selected a list of roughly 20 people, including people who live in Taiwan and people who have been imported to Taiwan, Neil Denari for example, Jesse Reiser, there's also people like me who sound and feel American but identify strongly as being a Taiwanese-American or a Taiwanese-Canadian.

Amy Frearson: Can you explain your relationship with Taiwan?

Jimenez Lai: I was born in Taiwan and moved away when I was 12 to Toronto, so I am also Canadian. There are a lot of people like that in this video, who are sounding like foreigners but are carrying a piece of Taiwan with them.

Then there's the exhibition. I guess what's difficult with the exhibition of architecture these days is that we rely on representations of architecture, but this I would say is architecture. Architecture as exhibition on a 1:1 scale. So dealing with the theme Fundamentals, we began by thinking about possible origins, let's say the Batman Begins of architecture. Once upon a time, even when we became biologically modern, we were living in caves. We know that we naturally we wouldn't shit where we sleep, and we couldn't eat where we crap. So the process of compartmentalisation began a long time ago, and this process may have been intensified over the last 150 years, now that we're able to afford privacy. The standardisation of the domestic programme, or the domestic diagram, is a modern phenomenon.

So if we'd never set out looking for a two-bedroom cave to live in, we wouldn't have two-bedroom houses. What we wanted to do was to isolate and condense the programmes and make them single-programme houses. So we have nine single-programme houses in this interior and the scattering of the nine houses form a kind of urbanism on the inside, where we're maybe walking on the streets between the houses. Or we can also think of a kind of figure-ground relationship where you and I are standing inside of a wall.

Amy Frearson: Can you talk me through the ideas behind some of the houses?

Jimenez Lai: So here you're looking at the House of Social Dining, where we're looking at the politics of geometry and the Western culture of eating around rectangles, where you can assign power. With the politics of geometry, as far as rectangles are concerned, we can create relationships. But a circle definitely softens the power structure. It doesn't mean that it doesn't have a power structure. If you inscribe a circle inside a square, depending on how you orientate the square to the entry, you can still assign power.

The geometry of the relationship is also something we're looking at. The pentagon, if we don't see it as a house, is just a five-sided shape with three perpendicular angles and two obtuse angles. But then one could say that the pentagon has evolved into an ideogram or a hieroglyphic. It's performing the role of language. We see this pentagon as a house in almost every culture these days.

There's also the House of Shit. We were also looking at the functions of spaces. The function of taking a crap is unavoidable, everyone has to. But then going to the bathroom does something else. The bathroom is the ultimate fortress of solitude. You're totally alone, you have absolute privacy, it's actually really enjoyable if you think about it.

Amy Frearson: What about some of the others?

Jimenez Lai: We also have the Altar of Appearance and the House of Pleasure, which look at the living room. The living room is interesting if you perform a kind of analysis. Some people's living rooms are actually used, they sit there in their underwear and watch TV and eat chips. I don't do that, but I know some people do. But some homes also have a living room specifically for the guests. Some people can afford that. That kind of living room has the best photographs, the best armchair, and is seldom used. It's almost like a vitrine or a shrine of your family, a representation of an ideal state. Since you seldom touch it, or are frowned up on for touching it, it's like a museum, a little museum of your home.

Amy Frearson: What elements have you looked at that are unique to Taiwanese homes?

Jimenez Lai: Some of the concepts are maybe more difficult to explain. For example, there's a culture of worshipping ancestors for Taiwanese people, and a lot of homes have little models of the home from generations of ancestors. So the ancestors are inside of this model home and on holidays you put out food in front of them. I was thinking about this kind of scale shift, and the articulation of architecture for the past ones.

Amy Frearson: What do you think is the overall message of the exhibition?

Jimenez Lai: One of the themes is a deep analysis of heroes that we look up to in architecture. We're not only being contextual to the environment, we're being contextual to history in some ways. I think there's joy in embedding Easter eggs, there's joy in finding them and there's joy in being found, and so there will be people who identify with the references we're looking at and I'm very happy when this happens.

Amy Frearson: Was adding an element of fun an important part of the project?

Jimenez Lai: Maybe by accident. I think there is a function to the curve and a function to the filleted edge. They soften relationships. It does perform the function of say music even. We have certain reactions to colours emotionally, and we have certain reactions to major tones and minor tones in music. Over the years I've also really thought that some sensations from receiving minor tones are similar to certain colours that we know. So then by the composition of different kind of colours, from warm to slightly cool, we're able to create a sense of optimism.