A mile-long street provides play space in this conceptual skyscraper by RCA graduate Elly Ward, which examines how children's experience of and contribution to city life can be enhanced (+ slideshow).

Elly Ward's MA graduate project for the Royal College of Art's School of Architecture is entitled The Child and the Vertical City.

It looks at how children live in cities that are increasingly dominated by high-rise apartments and takes as its starting point a simple question: if the only way is up, where will the children go?

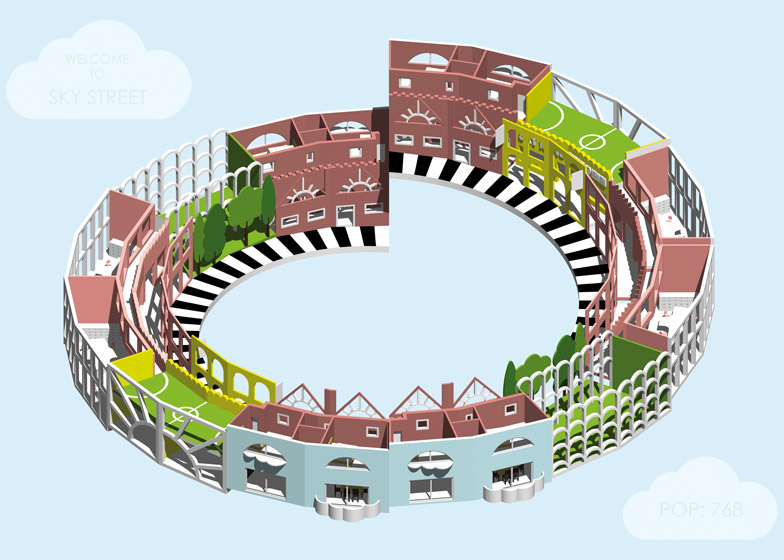

Ward's Sky Street tower proposes a solution, with shops, workplaces and homes incorporated across 32 storeys to create a vertical neighbourhood, and a circulation route winding from top to bottom to encourage interaction.

"Children used to learn about society through street play and direct interaction with civic life," explained Ward, who recently founded London studio Ordinary Architecture with former FAT director Charles Holland.

"Today, however, a combination of motor transport, technology and our increasingly risk-averse culture severely restricts such opportunities. Children find themselves isolated not just from the street, but from all the messy vitality of the city itself. And of course the child's loss is the city's loss too," she told Dezeen.

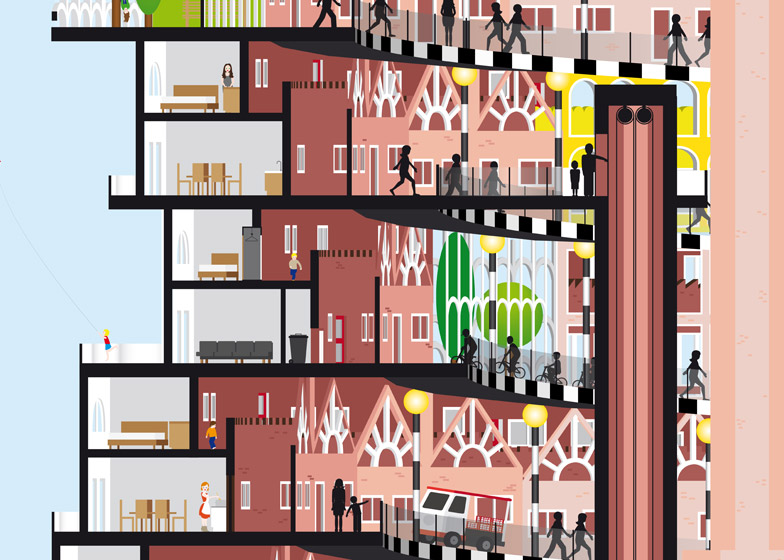

Ward designed a layered circulation for the tower, with a three-metre-wide ramp providing the main route up and down, and a secondary stepped circulation route offering a screened layer of semi-public frontages to the buildings that wind up the tower. A third circulation route is designed just for children, occupying the tower's rooftop spaces.

The concept revisits the "streets in the sky" concept championed by architects including Alison and Peter Smithson, who integrated communal circulation routes into buildings to encourage interaction.

As part of her year-long research for the project, Ward also co-led a workshop for schoolchildren to make mixed-use vertical cities out of Lego at London's V&A museum.

"I found the children were far more adventurous in both their combination of uses and their formal ambition," she said.

"The new market-rate, high-rise building type is set to rapidly populate the London skyline over the next decade, but its current form is so normative, borne out of a desire for efficiency rather than community, with circulation that tends to be strictly functional and often actively restricts interaction," she added.

"Inspired by this child's-eye perspective, my proposal offers a speculative alternative for the future of high density, urban living."

Here's a more detailed project description from Ward:

The Child and the Vertical City: A New Street in the Sky

'If the only way is up, where will the children go?'

The continuing housing crisis provides an opportunity to re-examine post-war ideas about how to accommodate workers and their families in our increasingly vertical city. This proposal for a 32-storey tower revisits 'streets-in-the-sky' as articulated by the Smithsons et al. and takes the theory to its absolute zenith with a one-mile-long continuous street spiralling upwards through its interior.

A design that could be described as Park Hill meets the New York Guggenheim meets Torre David, Sky Street radically re-interprets the idea of a 'mixed-use' tower to create a vertical neighbourhood that embraces and encourages civic interaction. Children play close to both home and workplace, the morning school run and the daily commute circumnavigate each other, and the milk delivery and rubbish collection take centre stage on the street.

Primary public circulation is via a three-metre-wide central spiralling ramp - distinguished by the black and white stripes of an endless zebra crossing. Secondary stepped circulation provides a screened layer of semi-public frontages to the apartments, offices and public amenities. A further tertiary self-contained route runs along the rooftops of the units below and is just for children - perhaps accessed through a secret door in their wardrobe - connecting directly to larger breakout spaces and making use of SLOAP on the top of retail units, transforming it into P(lay)-SLOAP. Four lift shafts in the centre of the tower serve as both structural core and motorised circulation for speedier transit, with lift stops strategically placed so as to encourage interaction on the main spiralling street, to which they are linked by a series of bridges.

The tower offers a typological model of typical units that can be assembled in a variety of different combinations, and grouped with further towers, introducing richness and vibrancy in a typology that tends towards standardisation and repetition. Typical floors are subdivided into smaller neighbourhood blocks of up to 16 units. Individual units are arranged over a minimum of two floors (sometimes three or four) and accommodate a split of residential and office uses which are served additionally by public amenities - such as a corner shop or pocket park, on every floor - the nature of which changes from block to block. Further civic functions occupy different areas of each tower, such as a day nursery at the bottom and the Fourth Magnet public house at the top.

Sky Street exists in a scenario where corporations have once again assumed responsibility for housing their employees. It references various model or ideal communities such as Bourneville and Port Sunlight, re-imagining them not as garden city suburbs but as urban high-rise. Figurative street language and materials are used to suggest a civic quality to the interior. Externally the tower attempts to blend and disappear into the skyline, as much as any tall tower could, with sky-blue rendering and cloud-shaped balconies. And an occasional sunburst.

This project arose out of a year-long study into the child's experience of the city and how a former freedom to play on and learn from the streets has been degraded in contemporary society. The possibilities of this critique for society at large are ones which I now continue to explore in my own practice, Ordinary Architecture.