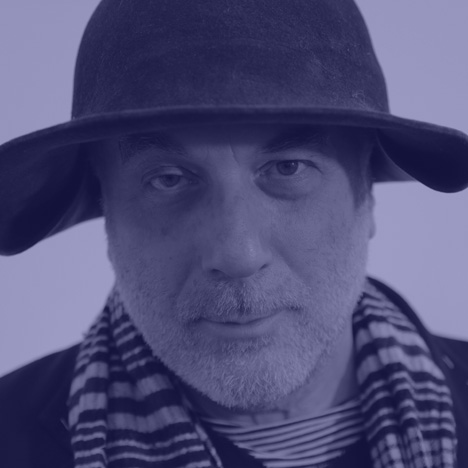

Dezeen Book of Interviews: in the first extract from our new book, Israeli designer Ron Arad explains how his career began with the chance discovery of a car seat in a scrapyard.

The interview at Arad's studio in north London was conducted in 2010 to coincide with the opening of Restless, a retrospective of his work at the Barbican gallery in London, for which Dezeen was commissioned to create a series of video profiles.

Besides the exhibition, Arad talked about how his career started. He left his native Israel for London in 1973 without knowing exactly what he was doing and ended up being interviewed for a place at the Architectural Association school.

He was accepted, despite not having bothered to take along a portfolio: "I was cocky. I was a brat," he said.

He later got a job at an architect's office in north London but walked out after discovering a Rover car seat in a local scrapyard. The leather seat went on to become the basis of the Rover chair, Arad's first iconic product, and he never looked back.

"I picked up this Rover seat and I made myself a frame and this piece sucked me into this world of design," he said. "If someone had told me a week before that I was going to be a furniture designer, I would think they were crazy."

Dezeen Book of Interviews: our new book, featuring conversations with 45 leading figures in architecture and design, is on sale now

Marcus Fairs: You've had retrospective exhibitions in New York and Paris. How does the Barbican show differ?

Ron Arad: One thing I don't like about retrospectives is that your life becomes a career. It's not a career. We go to the playground every Monday and interests shift and we get excited by something for a while and then we get excited about something else. If you want to call that a career, then okay, call it a career. It's more to do with getting away with things you like and not worrying about a career. I said before that we're more interested in doing new work, in showing new work, but having shows like at the MoMA in New York and the Centre Pompidou and the Barbican has its rewards and its magic moments.

My Tinker chairs, for example, are early welded pieces that were made by taking thin sheet steel, bending it and hammering it with a rubber mallet, welding it, sitting on it and deciding that bashing this or that a bit more will make it more comfortable. It's the nearest you can get to action painting in design.

What amuses me a lot is that this here is the Rover chair that normally sits in my living room. It came to my home before my daughters were born. They grew up, lived with it, jumped on it, all their friends jumped on it, never taking too much care of it. Then, at the Centre Pompidou, I wasn't permitted to touch it without white gloves. That is another sort of completion of the cycle.

Marcus Fairs: Which pieces of your work will be in the Barbican show?

Ron Arad: This Rover chair will be there and stuff of the same period that relied, more or less, on ready-made and found objects that were not ideology but necessity. I didn't have the industry behind me. I didn't know the industry existed at the time. It was something to do to keep me off the streets. Actually I had to go to the streets to find the stuff. It's not that I was a recycler, although the Rover chair was on the cover of the Friends of the Earth magazine. I'm happy about that, but that wasn't the starting point. If my activity was underpinned by anything, it was more to do with Picasso's Bull's Head and Duchamp's Fountain than with saving the planet.

You can't stay primitive for that long. You get better and better technically. When we thought we had a business in fabricating and making things in metal, just as we got good with it, I decided to stop, because I didn't want to become a craftsman. I didn't want to be, like, a fantastic glassblower or a potter on a potter's wheel. I don't have the temperament or the patience of a craftsman. So we subbed out the production to Italy and disbanded the workshop.

A similar thing happened at the height of the Rover chair's success. We decided to stop it because we didn't want to become a Rover chair shop. We cleared out the last 100 Rover chairs because it wasn't an exciting life to be in charge of production. It was exciting, initially, to go to the scrapyards and collect all the Rover seats and take them to this motor trimmer down the road in Kentish Town, which stopped taking any other motor-trimming work other than Rover chairs. So in the same way, when we got really good at making stuff, I stopped it and let the Italians do it.

The only problem is that they did things more perfectly than us. I enjoy the fact that my own work is not perfect and slightly rough. But the Italian Fish chair I'm sitting on here is an authorised fake. It's named after Gaetano Pesce. This is made in Italy. It's too good. Italian craftsmanship is better than ours. For some pieces it works and with other pieces we prefer the old ones. And collectors will only buy pieces that are made down here in the office.

Marcus Fairs: Is a lot of your work driven by chance discoveries of materials or processes?

Ron Arad: In the last century, we discovered rapid prototyping, which was sort of like science fiction. I started playing with it. We did an exhibition in Milan called Not Made by Hand, Not Made in China and it was, I believe, the first time that digital manufacturing was shown as the final pieces, not as the prototyping. We did lights and vases as the final product. It was very exciting until it became commonplace and it has been used and abused by lots of other people since. So there's some of that here.

Sometimes you hit upon a process, like the vacuum forming of aluminium, and it makes you think, "What can be done with this?" When I was commissioned to do a totem for Milan by the magazine Domus, my totem was made out of a hundred stacking chairs made in vacuum-formed aluminium, which is a process used almost solely in the aerospace industry. We developed the Tom Vac chair with it. The name comes from the fact that it's vacuum formed. And also there is a photographer in Milan called Tom Vack, who is still very active. Whenever he goes to a bar people ask him, "Are you named after the chair?" It's the other way around, though.

Later we did an industrial version of the piece with Vitra, which became a bestselling piece and was copied in China. I know about 14 factories in China that make the Tom Vac chair, and the way it started was with curiosity about the process. Then we discovered a factory in Worcester where they do deep vacuum forming. They inflate it and then suck it – it avoids wrinkles. Then I became fascinated by the blowing of the aluminium and I said, "What if the frames through which we blow this are not square but shaped?" And that led to a heap of work. There was a fascination with this amazing process that is a kind of hybrid between the will of the designer and the will of the material.

Like with everything else, we get better and better at it, we get more perfectionist and more demanding, enhancing the materials and the process and the properties of the material. This aluminium is very rich in magnesium, so it polishes more like stainless steel than aluminium and you can indeed do things with it that you could not do otherwise. But at some point you look at it and say, "I don’t want to do any more rocking chairs or polished pieces." And then you will do not only things that are back to front but also side to side, just to prove that you can keep your word after you declare that you don't want to do more.

Marcus Fairs: What is the most recent of your works in the exhibition?

Ron Arad: There's Rod Gomli – it's a piece that's loosely named after artist Antony Gormley, but spelled differently. It's based on the human figure. But it's everyman. It's not just one person. When you design chairs, you always cater to an invisible sitter who can be male, female, big, small, young, old. Everyone should be happy in it. I started to search for what the figure looks like, the invisible sitter.

Marcus Fairs: Is it actually modelled on Antony Gormley?

Ron Arad: No, I talked to Antony about it and I have a really nice picture of Antony sitting in the Gomli. It’s the opposite because Antony’s figure is him, is only him. This is everyman. The most recent work of mine is going to be the opening of the Holon Design Museum. Although the Holon project was five years' work, it's still the latest work of mine because it's about to open, in a month's time.

Marcus Fairs: Why is the show called Restless?

Ron Arad: The show is called Restless, maybe, because I am restless. To jump from one project to another, it's restlessness. I am not a methodical person. Also there is a lot of movement in the show. We had the idea that every rocking chair would rock, so the show is going to be very restless. There are a couple of last year's students of mine who are good with mechanical things who are developing devices to rock the chairs, some with timers, some constantly. There's that and there are lots of big screens and I have a book that is called Restless Furniture. I like that it's restless and that furniture is something people connect with resting.

Marcus Fairs: You were born in Israel. When did you come to London and why?

Ron Arad: I grew up in a very progressive home. Both my parents are artists. When I was young, I thought me and my friends were the centre of the world, like every group of young people does. Then I found myself here in 1973. I can't remember exactly leaving Tel Aviv. I didn't pack my LPs or anything. I just found myself here and somehow, without too much planning, I found myself at the AA.

I went to some parties at the AA. It was fantastic. I discovered the people who played invisible tennis in Antonioni's film Blow Up were all AA students, like hardcore socialist architects. It seemed like a good place, so I joined the queue. I didn't have a portfolio. I didn't take it seriously, going to the interview. When they asked me why did I want to be an architect I told them, "I don't. My mother wants me to be an architect." And that was true because every time I had the pencil she said, "Oh, that's a good drawing, be an architect," to make sure I didn't become an artist.

They wanted to see my portfolio. I said, "I don't have a portfolio. I have a 6B pencil. What do you want me to do?" I was cocky. I was a brat. Later, one of the people on the panel said, "Don’t do that again in an interview. We offered you a place but nearly didn't."

So I went to the AA. Then I tried to work for an architecture practice when I graduated, but I didn't last long. It's difficult to work for other people. After lunch one day, I didn't come back. The practice was in Hampstead and I walked down the street. I went to a scrapyard behind the Roundhouse. I picked up this Rover seat and I made myself a frame and this piece sucked me into this world of design. If someone had told me a week before that I was going to be a furniture designer, I would think they were crazy, but this piece sucked me in. I dread to think what it diverted me from.

Marcus Fairs: What happened after that?

Ron Arad: I found a space in Covent Garden – before Covent Garden was given over to multinationals. It was still an exotic place. I found myself a studio without knowing what I was going to do there. I started doing some things and it was really good being in Covent Garden where a lot of cultural tourists used to come and look for excitement. There was a very influential little shop by someone called Paul Smith with concrete walls and with a different display in the window every night, and an avant-garde jewellery shop.

My first place, One Off, was in Neal Street. I actually taught myself to weld because we clad everything in steel. When we moved out, we packed everything up and it was shipped to Vitra. At Neal Street was the cantilevered staircase that was, in a way, a keyboard of a synthesiser. As you walked down the steps, amazing music played, then you had to ask, "Can I buy the tape that you're playing?" This was before CDs. No, you just made the music.

After that we found this place in Chalk Farm, which had been a piano workshop and a sweatshop – when we got here there were sewing machines everywhere. We made this roof that was meant to last ten years, but 20 years later it's still here and we're still here.

Marcus Fairs: Your work straddles design, art and architecture. How do you describe yourself?

Ron Arad: I am a designer, but I do other things as well. We do architecture, we do design and we do work that is outside the design world. It lives in collections in art galleries and it makes it difficult for some people to accept that there's no... [trails off ]. I don’t like the word "crossover", I don't like terms like "design-art". It's all nonsense.

I think design is in a similar place to where photography used to be 20 to 25 years ago and people questioned the fact that a piece of art can be made using a camera and not an easel and brushes. That debate used to be interesting for a while, then it got boring, then it disappeared. Now, something that might suggest or hint at a function cannot be part of the art world. It's a very old-fashioned, conservative idea and I hope it will disappear.

There was a time when a debate was interesting between art and design and crossing over and working between disciplines. What's interesting now is what's in front of you: is it an interesting piece or is it not? I don't want to stop doing knives and forks for brands such as WMF to make it easier for curators to hold on to their job at some national institution.