Brutalism: challenging, idealistic and serious – Brutalism is architecture for grown ups, says Jonathan Meades.

Fashion is a tyrant we submit to insouciantly. This is not vouchsafed us until we realise that the thought or artefact or moral posture that we smugly assume is ours alone is actually shared by others and is spreading to the many. Nothing is immune from fashion. It infects the frivolous, certainly – and the grave too.

Totalitarianism was a European fashion, and remains an African one. The architectural expression of the secessionist and separatist will through Art Nouveau, Jugendstil and Romantic Nationalism was a fashion in countries and states that were, ironically, attempting to emphasise their differences and peculiarities. Sustainability is as much a fashion as multiple tattoos and Scandinavian thrillers.

Posthumous reputation does not escape fashion's grasp. When Francis Jeffrey, regarded as the leading critic of the day, wrote in The Edinburgh Review in 1829 that Keats, Shelley, Wordsworth, Coleridge and Byron would soon be forgotten whilst Samuel Rogers, Thomas Campbell and Felicia Hemans (you are, rightly, asking who?) would withstand the test of time he was making a fool of himself – a future fool, but that's a risk we all must take. He was also subscribing to that fashion which indicts the creations of the immediate past irrespective of their quality. Yesterday has something stale about it.

The day before yesterday and the day before that are, however, quite different cups of grog. They have been laid down. They have matured. They excite different prejudices. They belong to eras that are elusive and possibly so distant there are no human survivors, no direct witnesses. The extent of the temporal gap between us and them, between now and then, affects our understanding: we do not with any certainty know what, all those millenia ago, Carnac and Stonehenge were for.

It also affects our taste. The Victorians' high-minded contempt of their Georgian predecessors was born out of both the latter's perceived impiety and degeneracy, and an aesthetic objection to the rationalism, plainness and meanness of what much of the 20th century would come to regard as the ne plus ultra of domestic civilisation and good taste (forget Georgian dentistry, forget Georgian child prostitution).

The strength of the Victorian abhorrence is evidenced by the fact that what are accepted as the earliest exercises in neo-Georgian design were not made till the 1860s and were, anyway, not the work of architects but of writers, W M Thackeray and Wilfrid Scawen Blunt. And the eventually widespread, too long-lived (and mostly dreary) neo-Georgian revival did not begin until the very end of Victoria's reign, three generations on from the last of the Georges.

It took even longer, getting on for a century, for High Victorian buildings (ie circa 1850-1870) to be accepted as anything other than aberrational, ugly, risible, sanctimonious, pompous, churchy repositories of superstition: why should a town hall look like the house of God the Wrathful? Again, the bias was both aesthetic and moral. This, then, is the invariable combination: the ingredients' proportions may vary. Further, they may mask each other.

As Wilde discovered, England's peculiar culture deems aesthetic antipathy somehow invalid or enfeebled and frivolous. The only adhesive objection to a work of art – and this pertains well over a century later – can be to its morality, whatever that means.

Brutalism's opponents – who dare not simply own up to disliking the look of the stuff because it fails to accord with their preference (for the quaint, the picturesque, the pretty) – are adept at providing a host of reasons why such buildings are readily expendable. They are hygienically dubious, socially disastrous, behaviourally corrupt, confusingly planned ethical sewers, which promote criminality, family break-up and pissing in lifts.

London's Victorian slums, the rookeries – cute as can be at the distance of two centuries – were not, of course, anything like that. They didn't have lifts. They belong to the perennial dream of Golden Yore. A dream, which anyone who can be bothered to spare half a minute to look at the degradations represented by Hogarth or Doré will appreciate, is actually a nightmare.

My own first attempt to rehabilitate or at least draw attention to the merits of "big tech" was a film shot in 1995, Remember The Future: counter-intuitive cantilevered university buildings; cooling towers; the 330-metre-high transmitter mast on Emley Moor; listening stations etc. The emphasis was not exclusively on the XXXL structures themselves. The film was founded more in a sort of regret, nostalgia if you will, for what even then seemed a distant optimistic era when there existed a belief in progress and the hope of a tomorrow that broke with yesterday. It prompted incredulity and a degree of scorn. Was I a contrarian, thus merely perverse? Was I in earnest, thus playing with a ten man team?

Last year, two decades on, I made Bunkers, Brutalism, Bloodymindedness. The chances of a puzzled, let alone hostile, reception had, regrettably, now all but vanished. I was part of a concrete-inclined herd. What had happened? Bluntly: poet-Modernism and neo-Modernism had happened.

The presumption of the Gods of The Market is that we passively crave, above all else, the accessible, the approachable, the unchallenging, the bland, the readily legible. It is, I suspect, its very subjection to an unrelenting diet of these base qualities that has prompted a generation to decline saccharine architecture, fast-food architecture, "eezee-lisnin" architecture, instant gratification architecture in favour of the grown-up's architecture of getting on for half a century ago.

There was good Brutalism and bad. But even the bad was done in earnest. It took itself seriously, which is a crime in The Market whose insistence is on mindless fun and moronic fun. Just look at television.

The swell of appreciation is not confined to England where an unusually talented bunch of writers (Murphy, Hatherley, Wilkinson et al) has established a form of architectural investigation and exegesis founded in cultural theory, Nairn and psychogeography.

The French photographer Frederic Chaubin, the Belgian photographer Jan Kempanaers, the Canadian photographer Christopher Herwig and the English photographer Peter Mackertich all specialise in different forms of brutalism. So too do the collagists Neil Montier, Filip Dujardin, Bas Princen and Nicolas Moulin. There are countless fansites such as f*ckyeahbrutalism, magazines like the Manchester Modernist, and so it goes on.

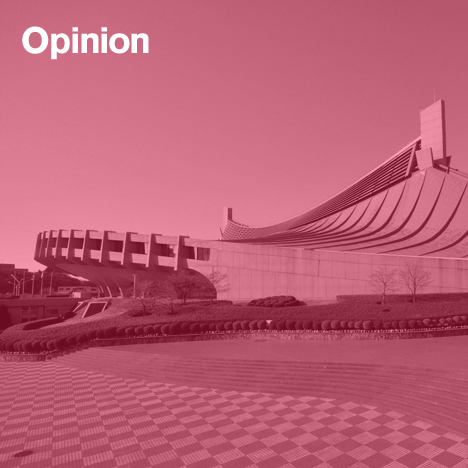

Too late, of course, to have militated for the preservation of Owen Luder and Rodney Gordon's masterpieces in Portsmouth and Gateshead. But representations of those lost structures, those noble structures, are already inspiring architects such as J Mayer H and Ortner & Ortner, not yet born when Gottfried Böhm, Kenzo Tange and Paul Rudolph were in their sublime prime.

It would be rash, however, to infer from the example of these practitioners that we are on the brink of The Great Brutalist Revival. Nonetheless, given that virtually every strain of modernism has been revisited and, if you like, plundered in the past two decades there seems to be every chance that raw concrete will once again have its day, or hour. It will of course be stripped of the meaning that was once attached to it. The notion that it might foment optimism, let alone utopian yearning, is improbable.

Jonathan Meades is a British writer, author and broadcaster. His most recent series of films Bunkers, Brutalism, Bloodymindedness: Concrete Poetry were shown on the BBC earlier this year.