World Architecture Festival 2014: architect Moshe Safdie has called for a "reorientation" of the way cities are designed, saying that the vogue for skyscrapers and the privatisation of public space is creating cities that are "not worthy of our civilisation".

"I think that we need reflect that our planning tools are no longer adequate, that the way we have planned in the past is no longer effective," Safdie said in the closing keynote speech at the World Architecture Festival in Singapore on Friday.

Architects today are obsessed with designing isolated towers, Safdie said, which increasingly feature privately-owned malls at their base. This is leading to disconnected cities where the notion of shared space is being eroded.

"I think most of the avant-garde in our profession today is preoccupied with fundamentally the object building," Safdie said. "The object building cannot make a city. Unless we resolve this paradox, we will continue to be producing urban places which are disjointed and disconnected and not worthy of our civilisation."

He called for an overhaul of the way architects think about cities. "The profession needs reorientation. I also think that our understanding of what urban design is all about need reorientation."

"I think what's happened to the public realm today is that the high-rise building block has not been resolved in terms of how it makes an urban building block," he said.

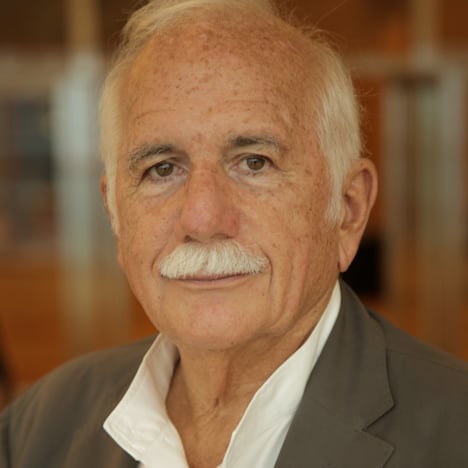

The 76-year-old architect is head of Boston-based Safdie Architects. He is best known for the pioneering Habitat 67 housing project in Montreal and the striking Marina Bay Sands development in Singapore, but he is working on a number of vast residential and mixed-use schemes around the world, including the 10-million-square-feet Chongqing Chaotianmen development in Chongqing, China.

After discussing his work he shifted to the topic of dense urbanism, which he described as "the most urgent issue of the day in terms of how cities are working".

In the past, he said, individual buildings and blocks coalesced to create common spaces such as streets, piazzas and souks.

"But the new typology is the superblock: a cluster of high-rise buildings of mixed use, sitting on a podium which is a retail mall," he said. "That's the dominant typology of the mixed-use downtown area across Asia, across Latin America and emerging now in every part of the world."

This has led to "the privatisation of the public realm" and an erosion of urban connectivity.

"These are private spaces, they are controlled privately," he said. "Secondly, they are introvert. They do not connect one to the other. It is rare, unless there’s intervention from a planning authority, that they connect with each other. They create a world, and another world, and another universe, each upon itself. Not as a connective city as it’s been historically. So this poses for us extraordinary questions."

This marked a decisive break with the past, he argued. "If you look back throughout the history of architecture, in each era where there was a school of thought, or an approach to architecture, it applied to architecture and it had an urban equivalent," he said.

"One could not conceive of an architectural conception that didn’t embody in it an urban conception, so that it became clear that when you design a building it’s a part of a city, part of a whole. When you conceive of a [building], you also have a philosophy about how it makes the city as it joins other projects. I don’t think that’s true today."

He called for a new approach to urban design and planning. "Having taught it for many years, I would say that urban design, until now, has dealt with the assumption that you can plan land and have some minor interventions through regulatory concepts about what happens three dimensionally in the city. But I think urban design now has to be conceived and implemented in three dimensions. It somehow has to apply to the private and public land in questions. You cannot plan the city without regulating what happens on the private land in relationship to the public land. And that's a new ball game."

He described Singapore as "probably the most advanced place in terms of thinking that way". His Marina Bay Sands development, which includes a shopping mall, a museum, a transport hub and a conference centre as well as the iconic, triple-towered hotel, doubles as a civic space, providing connectivity between the city on one side and Gardens by the Bay on the reclaimed land on the other side.

This was achieved because the Singapore authorities imposed strict conditions on how the land could be used and the quality of the architecture and urban design.

"Singapore has the advantage that much of the development was being implemented on publicly owned land before being sold," he explained. "Through the act of selling that land, the planning was controlled."

Concluding his lecture he said: "To me, how we come together to make all our individual building efforts come together to make a better city is the most exciting thing to explore right now. I wish for our profession that we go forward with a sense of the city as much as we [look for] the next wow effect."