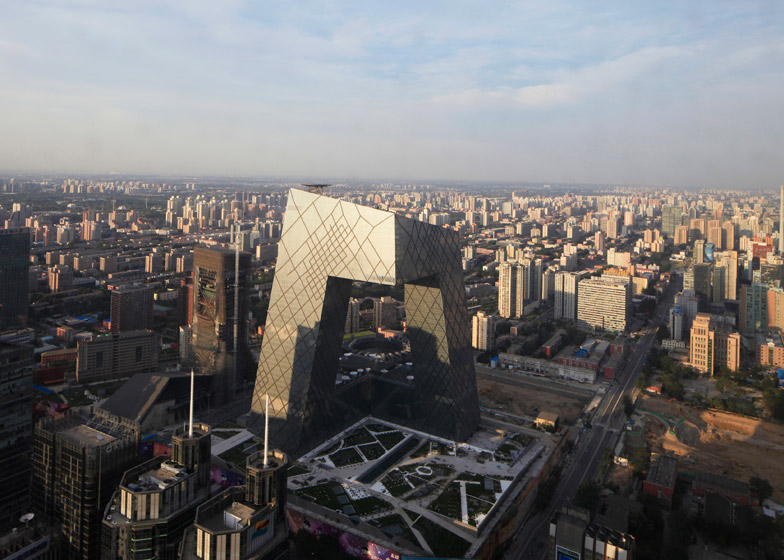

World Architecture Festival 2014: after working as project architect for OMA's giant CCTV tower, architect Ole Scheeren stepped out of Rem Koolhaas' shadow and set up his own practice in China. He spoke to Dezeen about what he learned from his former mentor and the vastly different speed, scale and ambition of working in the east (+ slideshow).

"Asia clearly has a series of attributes that differ from Europe," said Scheeren, shortly after delivering a keynote speech on the future of cities at the World Architecture Festival in Singapore last week.

"The two most obvious ones would be scale and speed, but I think there is also an even more fundamental one – a certain fearlessness and vision for the future. It is a dedication to what the future may be like without the fear of losing something."

The German-born architect spent "15 incredible years" working with Rem Koolhaas, before leaving to launch Buro Ole Scheeren in 2010. As the partner in charge of OMA's Asian output he was the driving force behind Beijing's CCTV building and Singapore housing project The Interlace, but wanted to move away from the "antiquated model" of exporting projects to Asia from the West by basing himself in China.

"I think having worked in this context has instilled in me a certain amount of courage to challenge things beyond the states quo that very much exists in most architecture," Scheeren told Dezeen. "It has given me a kind of freedom to think broader and maybe also sometimes a freedom to be more bold in my propositions."

"Obviously one of the features of China and Asia is that speed by far exceeds that of the West so you have to be incredibly agile and incredibly alert at every point in time," he added.

Scheeren's current projects include a Kuala Lumpur skyscraper with a four-storey-high tropical garden slicing through its middle and a pair of Singapore towers that curve around public plazas – buildings he says will "challenge the singularity of architecture".

"I think architecture has become increasingly objectified, but not in the positive sense of the term" he explained, describing his distaste for buildings "designed as something that can be easily communicated in an image" and his ambition is to create "humane" spaces.

"It is very easy to photograph an object, but it's very difficult for an image to capture space. I'm very interested in going beyond that. It doesn't mean the buildings we do can't function as objects, but they also function as other things. You don't have to deny something entirely to accomplish something else. You can create new hybrids that simply accomplish more."

Scheeren revealed he is also working on a "very very tall building" that could become the largest structure in the world – but insists that buildings can't be just about height if they want to have meaning.

"Height cannot be the ultimate goal of a skyscraper because if that is its legitimisation then it will lose it very soon after," he said.

"I think densification of this world is unavoidable. Density of cities is unavoidable. Therefore verticality will increase but the question is, what models we can develop to address that verticality?"

Scroll down to read the interview in full:

Amy Frearson: What was your strategy for moving away from OMA and starting your own practice? Did you have a distinct idea about what kind of projects you wanted to work on?

Ole Scheeren: One thing I was interested in at that moment was the hypothesis of headquartering our office in Asia, so no longer being in Europe but ultimately still producing everything in the West and sending it over for execution in the East, which I think is an antiquated model of operating. I was very interested in placing us even more very explicitly into the context in which I had been working for almost a decade already. So that was one motivation. It was also a point in my career when I had spent 15 incredible years with Rem, which was really the best that could have ever happened. But I asked myself: what do the next 15 years look like? Having completed CCTV, it was a great moment for me to start my own office.

Amy Frearson: What do you think are the main lessons you took away from those years with Rem?

Ole Scheeren: It was obviously an incredible time, with the incredible opportunities he gave me and the office, starting with the projects for Prada that I was in charge of, at the end of the 90s and early 2000s, doing the stores in New York and LA. And then, the shift to Asia and the CCTV tower.

I think what was interesting about these two projects was that they almost represent the most extreme opposite ends of the scale-spectrum of the office. Prada was in a way was almost the smallest serious thing the office had ever done and CCTV by far the largest, so when I took on that project it was actually three times everything I had ever built in 25 years. So in a way it gave me a very acute sense of scale difference. In Prada we really controlled very screw, every little joint, every material to the absolute degree, and then going to a scale of a 600,000-square-metre project in China.

Amy Frearson: What were the benefits of moving your office to China, besides the proximity to the projects you were working on?

Ole Sheeren: One is that I have incredibly good relationships with all my clients, mainly because I'm there and have been there for a long time. We're not opportunists that are in China and Asia because Europe is not doing so well. We have made a commitment to it that they really value and recognise the value of that. So I think that's a very important basis for a much more intense and deeper dialogue.

The other is obviously that living in the place that you work for that period of time makes you acutely aware of all the things that are happening, of all the fluctuations, and it puts you into a position to react much faster. Obviously one of the features of China and Asia is that speed by far exceeds that of the West so you have to be incredibly agile and incredibly alert at every point in time.

Having said that I'm now also, after more than a decade of focus on Asia, looking back at Europe and starting an operation there that allows me to really look at what the benefits are, from having worked in both contexts for a long time. The first chapter of my life was building in Europe and the second in Asia. The value of our work is that we're utterly familiar and embedded in both contexts simultaneously. And I think the possible transfer and synergies between that have a lot of potential.

Amy Frearson: Having been based in Asia for a while, how do you think your ideas on architecture have changed, especially now you're looking to work in Europe again?

Ole Scheeren: Asia clearly has a series of attributes that differ from Europe. The two most obvious ones would be scale and speed, but I think there is also an even more fundamental one – a certain fearlessness and vision for the future. It is a dedication to what the future may be like without the fear of losing something. I think having worked in this context has instilled in me a certain amount of courage to challenge things beyond the states quo that very much exists in most architecture. It has given me a kind of freedom to think broader and maybe also sometimes a freedom to be more bold in my propositions.

Amy Frearson: Do you think that because in Europe we're so concerned with preservation, that it prevents us being forward-thinking enough when designing for cities?

Ole Scheeren: Of course preservation is an incredibly essential thing and we are also involved in an number of ways in the Asian context in discussing how preservation could play a bigger role where maybe it is disregarded to often. But I think in Europe I see a potential to not disregard any of those values but nonetheless work beyond them at the same time. Clearly Europe is a context that requires far more subtle manoeuvring than the Asian context does. But again we're very capable of that and also very interested in doing that.

Amy Frearson: It touches back on something you mentioned in your keynote speech about the idea of not thinking about a building as a single object and instead trying to think about how buildings frame spaces. Is that a theme throughout your work?

Ole Scheeren: For me there is a really a campaign to move beyond the object and I think architecture has become increasingly objectified, but not in the positive sense of the term. Really it is more and more designed as something that can be easily communicated in an image, because the image rules everything at this point, through the internet, through more traditional publications. The image is how architecture is usually communicated when architecture is not experienced in reality. It is very easy to photograph an object, but it's very difficult for an image to capture space. So obviously all of that – along with the the icon obsession and other things – has manoeuvred architecture into a very object-driven singularity. I'm very interested in going beyond that. It doesn't mean the buildings we do can't function as objects, but they also function as other things. You don't have to deny something entirely to accomplish something else. You can create new hybrids that simply accomplish more.

Amy Frearson: I guess the difficulty is that architects often just deal with a small parcel of land and don't necessarily have to think of the bigger picture. How do you think we can move beyond that?

Ole Scheeren: I think a number of the projects I have shown today demonstrate exactly the possibility to conceive a project within a much larger context. I think in that way our work is actually highly contextual and incredibly specific to each position that they actually inhabit. I think most of them, from the Interlace to Duo, to Ankasa Raya to Bangkok, MahaNakhon and also CCTV are all projects that challenge the singularity of architecture.

Amy Frearson: You mentioned the Interlace – do you think this project sets the standard for the kind of buildings you want to make at your studio?

Ole Scheeren: What I think is significant and radical about the Interlace is that it is a blatant reversal of a typology that is probably more straitjacketed than most others. Housing – through the quantities that it has been produced in, and the formulaic nature that it has taken out of an almost lethal mix of building regulations, efficiency and profit concerns – has become simply compressed into a very standardised format. I think this project shows in a really dramatic way, and also in a significant scale, that really something else is possible. It's really a mass housing issue, and in that way I think it's a very important prototype that I've created.

Amy Frearson: How would you compare your ideas for mass housing to the architecture of the 1960s, to those large-scale housing projects that had the same ideals but never quite worked out the way they were intended to?

Ole Scheeren: I guess in the 1960s there were a number of really good ambitions and really powerful ideas but maybe what was missing was yet a sensitive enough understanding of the humane, of structures for inhabitation. They were incredible structures, and really interested in using this structural dimension, but to really embue it with a very acute sense of place, of space, of inhabitation of people who actually live and work and exist in those places. I think that also is very explicit in the Interlace, although it's a very abstract system per se, it actually creates completely non-abstract realities within it, and I think that for me is the success of it.

Amy Frearson: And is it true that when you were designing you had all of your staff make stick figurines of all the people that will inhabit the building?

Ole Scheeren: Yes, it was a really intuitive reaction, because I looked at my team working and they actually filled an entire office floor, and I looked at the plans we were drawing and I realised the size of our entire office floor equalled the size of the building core of CCTV. So I basically shouted at everybody to stand up, form a square around the outline of the space, and I said: "Now look at this space – this is just the elevator bank of what we are designing." And I think it is these moments of reality checks where you confront yourself and your own team with these realities. I think it's incredibly important to inbed these moments of surprise and realisation, realisation especially, in the process of design.

Amy Frearson: I imagine a lot of architects working on huge projects and skyscrapers probably don't have that understanding of scale.

Ole Scheeren: Exactly and this is why so many buildings become abstract, and why everything is scaleless. The problem with all big projects is they are scaleless, and I'm extremely interested in how we can find scale in scalelessness.

Amy Frearson: Do you think the ongoing race to design taller and taller buildings will continue or do you think architects will start to think smarter about buildings?

Ole Scheeren: I think the discussion has clearly started on a relatively broad level already to make buildings, one one hand, more sustainable and, on the other hand, hopefully more liveable. I think a lot of this discussion still circles around alibi, rather than true qualities – I think that shift is a much more radical one that is also not that easy to accomplish – but I think to propagate a floor with a little elevator interchange is the new urbanity of the skyscraper, for example. It's not quite there, so I think there's a long way to go. Obviously we're trying with our work to find projects that can constitute possible examples for how we an explore that. I think densification of this world is unavoidable. Density of cities is unavoidable. Therefore verticality will increase but the question is, what models we can develop to address that verticality?

Amy Frearson: In your keynote speech you said "buildings can no longer be about height if they want to have meaning" – can you tell me what you mean by that?

Ole Scheeren: I think CCTV was one of the first emblematic statements where we proclaimed that height cannot be the ultimate goal of a skyscraper because if that is its legitimisation then it will lose it very soon after, because someone else will build taller. Also the inherent problem with verticality is it's a very hierarchical value system. If you build a tower, who wants to live on the third floor of a 50-storey building? These issues are undeniable.

We continue to work on tall buildings and I'm actually now involved in a study I can't say too much about yet but it's a very very tall building – it could be the largest, although not necessarily the tallest structure built in the world to date. We cannot reject any scale per se, but we really have to challenge the systems that generate them and maybe reinvent some of the systems in order to function at those new dimensions.

The Interlace was an anti-tall building, although really it was a skyscraper and a tower nonetheless. If we look across our own website we see a great wealth of ideas, some of them more reasonable, some of them more courageous. The question is: "how do these ideas become relevant in reality and how do they translate into reality?" It is very easy to just stick with what everyone else is doing, it's also not that difficult to have a few crazy ideas beyond it. Really the challenge is to develop ideas that can function in reality and push the boundaries of that reality.

I think CCTV would be a completely irrelevant project if it was simply on paper and if we had not built it. There were many good ideas but I think what makes it really relevant – and the same applies to the Interlace – is that these two very significant-scale projects totally shifted the boundaries of the possible. But they are real, because they understood the systems that govern the architecture construction, cities, and other things, and became possible in those systems and beyond those systems. I think that is really the challenge – to understand what can work in reality. I'm very interested in reality, and how ideas can affect reality.