Biennale Interieur curator Joseph Grima and his research collective Space Caviar took over a derelict school in Kortrijk to create an exhibition exploring how perceptions of the home have changed over time (+ slideshow).

SQM: The Quantified Home formed part of the cultural programme curated by Joseph Grima and Space Caviar for this year's Biennale Interieur design event in Kortrijk, Belgium, which concluded yesterday.

The Genoa-based collective used the event to showcase their research into how the idea of "the home" has changed over the past century due to technological developments, economic shifts and globalisation.

"What I [wanted] to do is to look specifically at the home, at the core space that Interieur's mission hinges on, which is the domestic space," Grima told Dezeen.

"What transformations have taken place even in the brief timespan of our lives of thirty, forty years – and to speculate also on the directions it's headed and how design can once again be relevant to this."

SQM: The Quantified Home is accompanied by a book with the same title, a film named Fortress of Solitude and an installation at Biennale Interieur's Xpo site called the Theatre of Everyday Life.

"The reason for the title SQM is square metre," said Grima. "It's kind of a very loose reference to a hypothetical currency, the square metre – which is a currency that has an unequal value across space and time."

The exhibition was housed in the Broelschool, a former education complex that is set for demolition to make way for luxury houses.

"There's something really interesting about this beautiful building being demolished and to see the cycles of regeneration," Grima said. "This is also something that we wanted to use as an opportunity to comment on the home's relationship to the urban landscape."

As the building's fate is sealed, Space Caviar and graphic design studio Folder had free reign to intervene with the structure.

During a five-day workshop in September, around 15 designers in two teams camped in the building while they knocked through walls to create shortcuts through the structure.

"We inhabited the school for a week and scavenged for materials and items, and used only things that we'd found in the school to make an intervention that creates a path of approximately 300 metres that winds up through the building and falls back down again," said Grima.

The new route was marked by an overhead electricity cable that also powers a series of light bulbs along the way. The journey around the exhibition began in one of the oldest parts of the facility and led through to the newer areas.

To access the entrance – a hole in a first-floor external wall – visitors had to climb an angled staircase with risers of uneven heights and treads that narrowed towards the top.

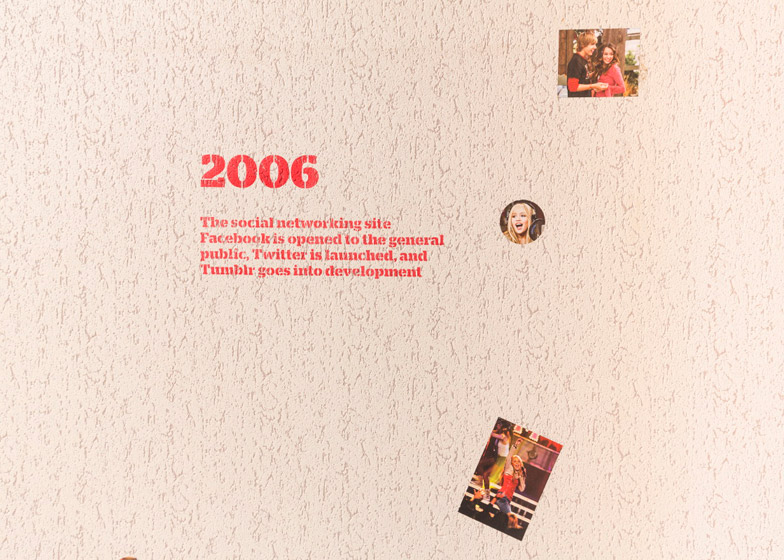

Once inside, they were tasked with locating short pieces of text printed in red on the walls or within cupboards, which provided information about significant moments that altered or questioned the concept of home in some way.

These snippets of information, peppered with major historical events, were organised in chronological order along the route marked out by the yellow cable. Each was paired with a relevant quote, located elsewhere in the same room.

"Along the 300-metre path we tell the story of historical events and facts of the home's transition over time and certain pivotal moments of how we got to where we are now," Grima explained.

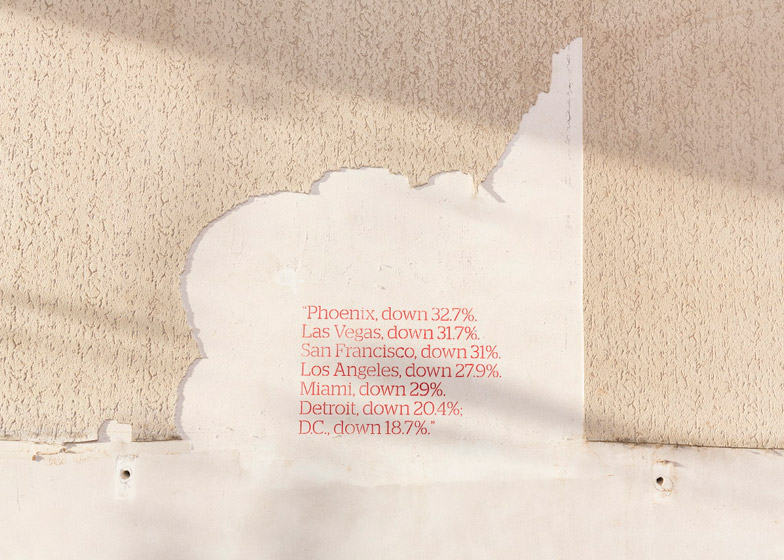

Along the way, architectural and decorative elements both inside and outside of the building were subtly manipulated to display data and statistics that back up the information written on the walls.

Some of these were viewed through holes in the masonry, reflected in bathroom mirrors, or visible from the windows of the upper storeys.

For example, a pair of adjacent rooms with blue and pink carpets were used to make a gender comparison. Sections of carpet were removed up to markers above the skirting boards to show how much time men and women each spend in the kitchen.

"I think we've collectively gone beyond the very traditional idea of the Victorian home as a very formal, almost ceremonial space," said Grima.

"But even the ideas that our parents related to: the Modernist home as a space of liberation from conventions and a space in which design can be an expression of ourselves through the curation of objects."

Blocks of red displaying the percentage increase in London housing prices each year were painted between vertical wooden supports in the attic, while another graph on a rooftop charted the number of annual users of home rental service Airbnb since its inception.

"[Airbnb] is an interesting phenomenon because it points at the home as a space of entrepreneurship," said Grima, "as a space that's part of the economy not only in terms of its role as an engine of lending for the mortgage industry, but as an engine of micro entrepreneurship on the part of homeowners and even renters."

A patio was already divided into a paved area and a soil-covered area scattered with fallen leaves. This second zone was used to show how much land could be purchased for a certain fee in Cairo, while a much smaller square pile of leaves created on the paving proportionally represented how much land the same amount of money would buy in London.

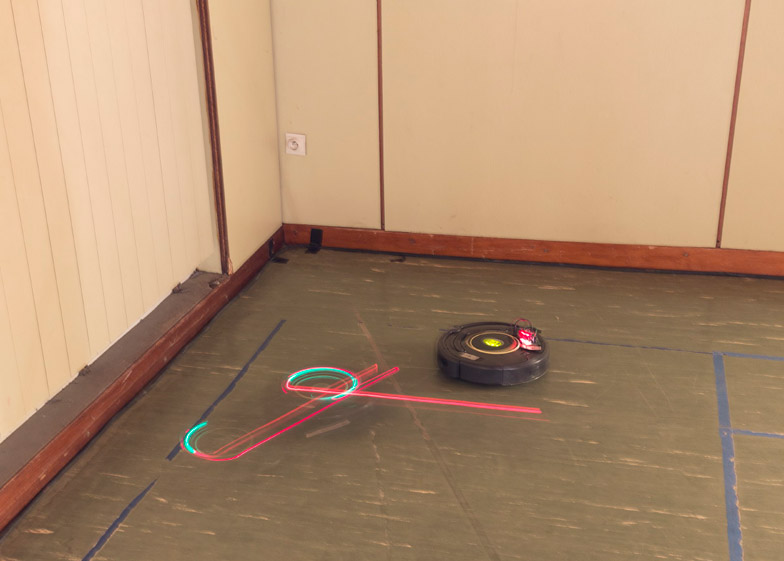

The final stage of the exhibition was the Roomba Ballet: a performance of robotic vacuum cleaners that were hacked and choreographed to dance a Viennese Waltz in the school's gymnasium as a "final celebration of this building's history".

The Broelschool also hosted a temporary hotel fitted out by different furniture brands and a display of geometric furniture designs during the design festival.

Photography is by Delfino Sisto Legnani.