Interview: ahead of his talk at London's V&A museum on Friday, typographer Vincent Connare has defended the reviled Comic Sans font he created, saying its detractors "don't know anything about design".

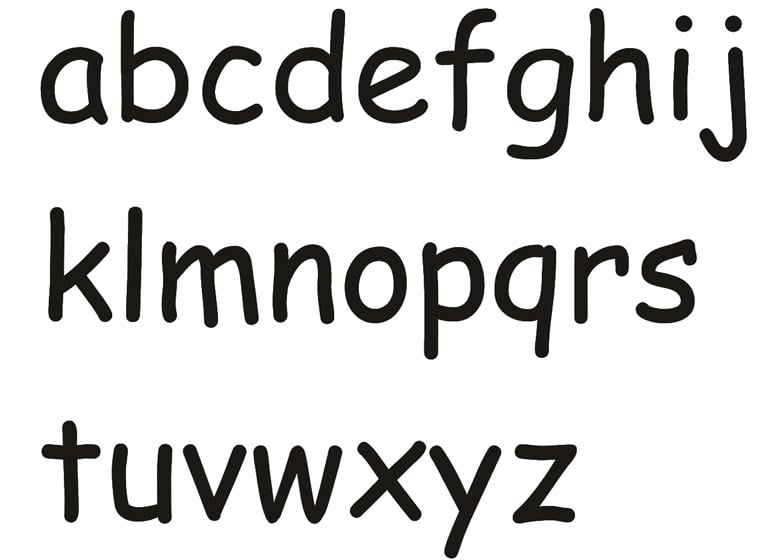

Designed in 1994 and inspired by comic-book speech bubbles, the ubiquitous sans-serif font has become the typeface that designers love to hate and even has a website dedicated to its abolition.

"I think people who don't like Comic Sans don't know anything about design," Connare told Dezeen. "They don't understand that in design you have a brief."

Vincent Connare was one of the early pioneers of digital typeface design, working on fonts for Agfa and Apple in the early 1990s before joining Microsoft, where he designed both the web-friendly Trebuchet font family and the now infamous Comic Sans MS.

"It was important at Microsoft to show people how things could be done. The group back then were doing things five years or more ahead of everybody," Connare told Dezeen. "We were addressing issues with various types of screens and devices. Today we are actually doing less internally in the code of fonts than we did 15 years ago."

Originally designed in 1994 to fill in the speech bubbles in a programme called Microsoft Bob, which featured a cartoon dog that offered tips on how to use a computer, Comic Sans was based on the hand lettering in comic books that Connare had lying around in his office.

"I was asked to comment on what I thought of the use of typography in this new application. I said I liked the drawings and cartoon characters and it was fun but I thought it was lazy to just use the system font Times New Roman in the speech balloons," Connare told Dezeen.

"I looked at the comic books I had in my office and drew up with a mouse on a computer an example of hand lettering that I showed to the group, with images of the cartoon dog Rover talking in this style of font. I did not intend to make a font. I was just showing them how I thought it would look better in a cartoon style."

Although the typeface was never used in the program it was originally designed for – it was introduced too late in the development process – it became popular in internal communications at Microsoft.

In 1995 it was included in the company's standard font package for Windows, putting it in the hands of millions of computer users. It was also included as a standard option in the Internet Explorer browser, expanding its reach even further.

"There are 200-300 fonts installed on every computer but people pick Comic Sans because it is different and it looks more like handwriting and does not look like an old school text book," explained Connare. "It is a personal decision. The same could be asked of why do people like Ugg boots, Justin Bieber or pink tracksuits."

By the end of the 1990s, the ubiquity of Comic Sans in home-made signage and children's school projects was beginning to generate a backlash from some designers. Critics felt it was being used "inappropriately".

In 2000, Connare received an email from Holly and David Combs, the founders of the Ban Comic Sans website, alerting him to the growing animosity towards his creation.

"Technological advances have transformed typography into a tawdry triviality," says the Ban Comic Sans manifesto. "Clearly, Comic Sans as a voice conveys silliness, childish naivete, irreverence, and is far too casual... It is analogous to showing up for a black tie event in a clown costume."

The V&A, where Connare is talking tomorrow night as part of its typography themed late night event What the Font?, describes Comic Sans as "one of the most popular and despised typefaces in existence" and cites its appearance on gravestones and government job applications as examples of its inappropriate use.

Connare once described the typeface as "the best joke I ever told". He does not regret creating it and believes that people who don't like Comic Sans don't understand the purpose of design.

"Comic Sans matched the brief, the brief of the entire Microsoft Consumer Division to put a 'Computer in Every Home' and to make something popular for the people of these homes and their kids. Comic Sans is loved by kids, mums and many dads. So it did its job very well. It matched the brief!"

Connare is now based in London, where he works for font foundry Dalton Maag training new designers.

"Anybody who says they would not like to design a typeface that makes such an impact and is used by so many people and on so many products, is lying to themselves," he said. "I would love to make something again that everyone loved and others would hate."

What the Font? takes place at the V&A from 6.30pm until 10pm and includes talks from Connare, typographer Jonathan Barnbrook and Christian Boer, designer of the Dyslexie typeface.

Read the full transcript from our interview with Vincent Connare:

Anna Winston: Can you tell us a bit about your background and how you became a typographer?

Vincent Connare: I began my career in type design back in 1987. I was living in New York City and decided to move back to Massachusetts for work. I started working as a photographer and darkroom technician but got bored of the hours and being in the dark for eight hours, so I applied to [typesetting systems company] Compugraphic in Wilmington, Massachusetts. I worked the second shift from 4pm to midnight. First I was converting their type library from a photographic library to the new Ikarus font format by URW in Germany. I then moved into the Intellifont hinting team, creating fonts for Hewlett-Packard Laserjet printers. In 1991 I was chosen to work on the new TrueType font format that Apple released. I created Agfa's (formerly Compugraphic) first TrueType fonts. In 1993 I began working for Microsoft in the Advanced Technologies research group. We later were reorganised into Microsoft Typography.

Anna Winston: What led to the development of Comic Sans?

Vincent Connare: In 1994 a program manager by the name of Tom Stephens came into my office with a CD called Utopia, this was the new application that was being released by the new Consumer Division. Its marketing manager was the future Melinda French Gates.

I was asked to comment on what I thought of the use of typography in this new application. I said I liked the drawings and cartoon characters and it was fun but I think it was lazy to just use the system font Times New Roman in the speech balloons. I looked at the comic books I had in my office and drew up with a mouse on a computer an example of hand lettering that I showed to the group with images of the cartoon dog Rover talking in this style of font as opposed to Times New Roman. I did not intend to make a font. I was just showing them how I thought it would look better in a cartoon style.

They liked it and asked me to continue to develop the font and that font became Comic Sans. It was not used in Utopia which was later named Microsoft Bob because the program was in its final beta and they could not change the default font at this time. It was used in another cartoon application called 3D Movie Maker. It got heavily used by the Microsoft administrative assistants in their emails and someone in marketing added it to the first Internet Explorer and the OEM version of Windows 95. This is the version of Windows that is given to computer manufacturers to install in their computers. So every computer sold with Windows 95 had Comic Sans in it and every copy of Internet Explorer had it too.

Anna Winston: What do you think it was about Comic Sans that made it so popular?

Vincent Connare: There are 200-300 fonts installed on every computer but people pick Comic Sans because it is different and it looks more like handwriting and does not look like an old school text book. It is a personal decision. The same could be asked of why do people like Ugg boots, Justin Bieber or pink tracksuits.

Anna Winston: What's the most unusual use you've seen of the typeface?

Vincent Connare: I think the most recent unusual use of Comic Sans is on the Spanish Copa del Rey league cup. The new cup uses Comic Sans to inscribe the years winners.

Anna Winston: When did it begin to feel like some people were turning against it?

Vincent Connare: Probably when I received an email back in 2000 from the people who set up the Ban Comic Sans site. I thought, if they have nothing better to do, why should I stop them.

Anna Winston: A lot of people say they don't like Comic Sans, why do you think that is? Does it bother you?

Vincent Connare: I think people who don't like Comic Sans don't know anything about design. They don't understand that in design you have a brief. Comic Sans matched the brief, the brief of the entire Microsoft Consumer Division to put a "Computer in Every Home" and to make something popular for the people of these homes and their kids. Comic Sans is loved by kids, mums and many dads. So it did its job very well. It matched the brief! No it doesn't bother me in the least.

Anna Winston: Has the public's changing relationship with Comic Sans affected how you think about designing typefaces now?

Vincent Connare: No. I think anybody who says they would not like to design a typeface that makes such an impact and is used by so many people and on so many products, is lying to themselves. I would love to make something again that everyone loved and others would hate.

Anna Winston: How important was that early work at Microsoft in the development of digital typefaces more generally?

Vincent Connare: It was important at Microsoft to show people how things could be done. The group back then were doing things five years or more ahead of everybody. We were addressing issues with various types of screens and devices. This was 15 years ago and it is now commonplace that we have to address type on these new small devices. Today we are actually doing less internally in the code of fonts than we did 15 years ago.

Anna Winston: Screens are becoming smaller and smaller with devices like the Apple Watch – what impact does this have on digital typeface design?

Vincent Connare: Small screens are not a problem. Displaying type on these screens means we have to do less. Something like a watch would have a limited amount of font sizes and doesn't need scalable font formats. If the font doesn't scale then you could just use .png or bitmap font formats like we used to do for screens or printers. These are fast and ready to display unlike outline fonts.

Anna Winston: What are you working on at the moment?

Vincent Connare: Currently I am working in the group responsible for training (called Skills and Process) at Dalton Maag. I am teaching new designers the reality of making digital typography and teaching them how to hint or program fonts.

Anna Winston: What makes typography different from other fields of design?

Vincent Connare: Type design and developing fonts is much more technical than other fields of design. The only other field of design as technical is web design and development.

Anna Winston: A lot of people use the words font and typeface interchangeably to describe the same thing. Is this a problem?

Vincent Connare: The term font doesn't actually apply anymore. The old word fount referred to the specific case of letterpress letters in a style and weight of a typeface. In modern use it refers to a specific font file such as Times Roman Bold. Typeface usually refers to the whole family of Times Roman. On computers the term font is synonymous with typeface because it is used in menus this way. If we want to be pedantic we could say the menu should say Fonts since it is a list of all the font names of the font files on the computer.

In French software, the menu reads: police des caractères. People use the term police to mean a font and a typeface too.