Moshe Safdie's huge greenhouse for Singapore's Changi airport gets underway

News: work has begun on architect Moshe Safdie's Jewel Changi Airport, which aims to "reinvent what airports are all about" by creating a shared public space under a glass dome with a massive waterfall and garden at its centre.

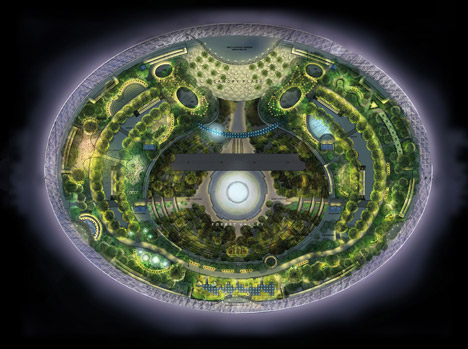

Safdie Architects' 134,000-square-metre addition to Singapore's main airport will combine retail, leisure and entertainment facilities with gardens to create both a public space for local residents and a facility for passengers passing through the airport.

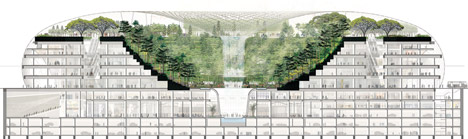

A 40-metre-tall waterfall – dubbed the Rain Vortex – will pour down from a round opening in the roof of the glass dome. It will be joined by an "indoor landscape" of trees and shrubs called Forest Valley, which includes walking trails for visitors.

Rainwater will be collected via the waterfall and reused in the building, and at night it will be the backdrop for a light and sound show that diners can watch from overlooking restaurant terraces.

"This project redefines and reinvents what airports are all about," said the Boston-based architect.

"The new paradigm represented by Jewel Changi Airport is to create a diverse and meaningful meeting place that serves as a gateway to the city and country, complementing commerce and services with attractions and gardens for passengers, airport employees, and the city at large."

"Our goal was to bring together the duality of a vibrant marketplace and a great urban park side-by-side in a singular and immersive experience," he added.

"The component of the traditional mall is combined with the experience of nature, culture, education, and recreation, aiming to provide an uplifting experience. By drawing both visitors and local residents alike, we aim to create a place where the people of Singapore interact with the people of the world."

The shape of the building is expected to serve a dual purpose – creating a natural focus point for the waterfall as well as providing structural strength to allow a more "delicate" latticework effect of glass panels framed in steel. Safdie conceived this aesthetic in "the tradition of glass conservatories".

Tree-like columns will be arranged in a ring around the edge of a roof garden, called the Canopy Park, to provide additional support for the roof. This space has been designed in collaboration with PWP Landscape Architecture.

"The suspended roof arches over the covered atrium, which is connected at multiple levels to the surrounding retail floors," explained the architect.

The route to the new building will be nestled behind the three terminals of the existing airport, which processes over 53 million passengers a year. It will connect to Terminal 1 with an expansion of the existing arrivals hall, and to Terminals 2 and 3 via new footbridges.

Work is due to complete on the project – Safdie's third airport building following Ben Gurion International Airport in Israel and Terminal 1 at Lester B. Pearson International Airport in Toronto – at the end of 2018.

Singapore has become an increasingly important market for Safdie, who has been working in the city-state for more than two decades. The architect's Marina Bay Sands hotel development, which opened in 2011, has become an icon on Singapore's waterfront.

Speaking to Dezeen at the World Architecture Festival in Singapore in October, Safdie said that Marina Bay Sands had opened up an eastern market for his firm, whose current projects include a 38-storey high-density housing project in Singapore called Sky Habitat and a 900,000 square metre development in Chongqing, China. "It's really put us on the map in Asia that's for sure," he said.

During his closing speech at WAF, Safdie called for a "reorientation" of the way cities are designed. He said that architects were obsessed with designing one-off towers in cities, creating disconnected urban environments and increasingly privatised public space, resulting in cities that are "not worthy of our civilisation".

"Most of the avant-garde in our profession today is preoccupied with fundamentally the object building," said Safdie. "The object building cannot make a city. Unless we resolve this paradox, we will continue to be producing urban places which are disjointed and disconnected and not worthy of our civilisation."