The fashion industry is "saturated" says Olivier Theyskens

Interview: the former head of two Parisian fashion houses has discouraged students from setting up their own brands because the industry is overwhelmed by too many new names.

Olivier Theyskens, who has previously headed Rochas and Nina Ricci, told Dezeen that the fashion industry is unable to cope with the surplus of young designers starting their own labels.

"It's saturated," said Theyskens during an exclusive interview during Seoul Design Week in November. "During New York's fashion weeks, you have shows with young designers when you barely have a third of the seats taken by people."

"These days, there is an over-offering of new brands," he added. "Now in every season and every fashion week, you have 10 or 12 new names. I think it's scary."

The 37-year-old Belgian designer dropped out of university to start his own label in 1997, during what he called a "boring moment" in fashion. After five years working on his own collections, he moved to Paris to head the creative team at Rochas before transferring to a similar role at Nina Ricci.

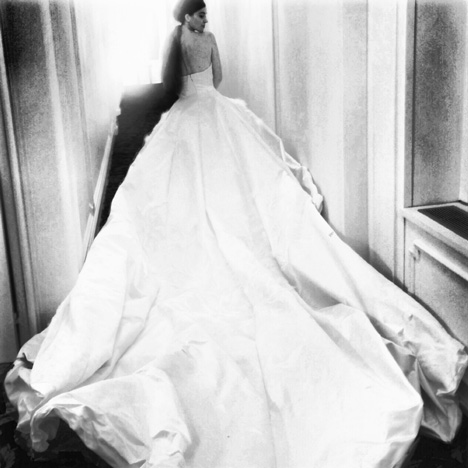

Four-and-a-half years ago, Theyskens joined New York-based brand Theory but left the company last June to pursue other interests – including spending three months creating a wedding dress for one of his friends.

For today's young designers wanting to follow in his footsteps, he believes that the internet – which didn't exist when he started out – is making it harder for them to get noticed.

"Professionals in fashion are overwhelmed with the images and websites. It's very tough to get their attention," he said.

As a solution to the over-saturation, he suggested that students interested in fashion should pursue other areas of the industry.

"They don't necessarily need to be 'the designer'," he said. "Students don't realise that there are other aspects of the industry where they could find a very strong place. A lot of kids that like fashion could become amazing merchandisers, they could become amazing sales people, they could become PRs or they could work more in ateliers."

Theyskens defended the role that unpaid internships play in the fashion industry and their importance to both companies and the individuals undertaking them, but warned that students shouldn't get into the habit of working for free.

"For a lot of students it's important not to get into a spiral of doing one internship after another. But they are not victims, they are people that are responsible for their own lives and the evolution of their life, and they are making choices."

Read an edited version of the interview below:

Dan Howarth: Can you explain a bit about your background?

Olivier Theyskens: I started my career about 17 years ago. I've had a lot of different chapters in my design life. For a while I had my own brand in Brussels, then I moved to Paris and I worked with Rochas and Nina Ricci there. Then I moved to New York and worked for Theory, which I left in June. So there's four moments.

Since I was born, I was obsessed with dresses and fashion. It came naturally to me. I went to school in Brussels for two years before I dropped out and I launched my own brand instantly. At that time, I was just making everything myself. It started very small of course, but very quickly it became a brand with a rhythm of shows in Paris.

Dan Howarth: What are you focussing on now that you've left Theory?

Olivier Theyskens: I only left Theory recently, in June. I committed to do a dress for one of my girl friends, she wanted the wedding dress of her dreams. I've been used to doing some of these kinds of dresses with ateliers that have whole crews that are able to work on it, but this time I thought I'm just going to do it. It's terrible but I worked for three months on that dress.

Dan Howarth: Do you think fashion designers need to keep that craft aspect?

Olivier Theyskens: It depends slightly. Fashion is always looking for innovation and the future, but if you just show a collection that looks like this building [Zaha Hadid's Dongdaemun Plaza in Seoul] in a way that's polymorphic and without seams, two seasons after if you keep doing that you're just going to make people bored. Two seasons after your should probably come back with a crafty, old-fashioned collection that you suddenly need seamstresses and the old ways for.

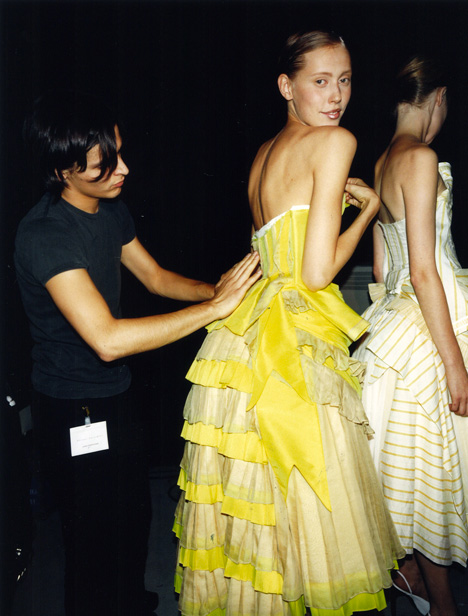

It's a funny thing for me, in fashion there is a lot of play with revivals and bringing back something old. My own way is to combine something old and something new. I think that with craft, there is now mystery about that when it comes to couture, it can be highly innovative but it can also be used to further perfect old types of manufacture to produce a garment.

Dan Howarth: [During a talk earlier in the week] Rem Koolhaas spoke about how as an architect he's learnt a lot from the fashion industry. Are there things that fashion can learn from architecture?

Olivier Theyskens: Of course. Many fashion designers train as architects before they start. When I work on the volume of something, I'm a bit of an architect. When I was younger, I did mock-ups of chairs and played with cubes. I would spend hours constructing things, I love it. I think we have something in common, a way to fold and bind materials to create volumes.

I'm not an architect because I love the body so much, there's something highly sensual in the approach to making something for the body. Working on androgyny, highly feminine, highly masculine things is something I'm attracted to. I always loved dance, I always loved the body. That's why I'm really into clothing, and I'm fetishistic on the aesthetics and beauty of people. But I love architecture, I love design in general. I think we have a lot of things in common. I might create a line of furniture one day, that would be something I'd love to do.

Dan Howarth: The fashion industry relies on internships. Do you think that they're useful and valuable?

Olivier Theyskens: It's good for certain people to do internships, I've seen some interns who have started to work at my place and learn a lot of things, and when they left I imagine someone could hire them. Though for a lot of students it's important not to get into a spiral of doing one internship after another. But they are not victims, they are people that are responsible for their own lives and the evolution of their life and they are making choices. If they don't want to do an internship then very well, they can go and find a job in another way. But some people find this a solution.

I really think we have to assist and help the maximum people that are starting their career and professional life, but at the same time they have to also be facing the realities. I always feel that it's fine for me to welcome a group of interns every season and I try to keep them for the shortest time possible. Enough time for them to learn what they need to learn and specialise in a certain activity, but after they have to go and find something else, or we should hire them. This is my ethic if we have an intern that is staying for six months in the company. If we are very happy with the work that the intern does, we should try to see a way we can hire that person and give them a real job.

The reality is that companies in fashion need a certain amount of people, but we can't have a huge team and teams are always evolving. Interns are coming at specific moments when activities are more important so they're a huge help. Sometimes I think they know it, and they're happy to be there, but they know it's because suddenly we need more hands.

Personally, when I dropped out of school I thought "oh god, what have I done?" I took all my personal drawings – I was drawing since I was a teenager so I had a huge pile of ideas, concepts for glasses and bags – and I went to Jean Paul Gaultier in Paris. The person who was there said that I had to leave all those drawings and wait for a call and I thought "I just can't leave this". It's a mind full of ideas, there are a million things there and I thought that I'd be taking a risk that I just didn't want to take. I kept my drawings and went back to Brussels and I decided I wouldn't do an internship.

But after, I found I wasn't prepared for some aspects of the activities – I don't know if I would have learned them from internships – but there was a lot of things that I still needed to learn about having a professional life with responsibilities. I wasn't really sure about how to face and manage them.

Dan Howarth: What was it like setting up your own company at such at early stage?

Olivier Theyskens: It was a very good idea, but I don't know if it's the best way nowadays. I didn't have much money at all, I was thinking that I should use the amount of money that school was costing me for my own things. I had a lot of little bits of fabrics that my grandmother collected for me since I was a child, a lot of things I could play with. I started to do a collection with what I had. It was impossible to produce after, so I couldn't take any orders but I used that collection as a way to present myself.

I did a proper show, all of the models were showing for free, everyone was just giving a hand. I got a lot of support and at the same time, I had started having some publications like in Face magazine and Isabella Blow saw some of my things and put them on the cover of the Sunday Times. The very early clothes that I did instantly had a very incredible group of people decide to shoot them.

I got recognition very quickly. People came to the first show that I did when I was showing things made out of antique fabrics and in my little showroom after the first person to open the door was the head buyer at Barney's. She couldn't believe that I didn't want to sell anything and I promised the season after that I would have something for them. It gave me time to meet factories, to convince them to work for me and to wait for payments. I found my way like that. I had no financial partner, it was very tricky and a lot of pressure working like hell, but it had to start one way or another.

Dan Howarth: Why did you decide to leave Theory?

Olivier Theyskens: I'd been at Theory for four-and-a-half years and I really wanted to learn about that field of the industry: how you engineer more accessible clothes and have a better organisation for production. In our world, it's an aspect that is crucial to understand. When I started at Theory I felt my role was different, it wasn't just about being an artistic director that says "I want to do yellow or orange". It was more partnering to make a company of that scale evolve and get to another level of its history. I felt that after the four years that we did it, my mission was accomplished in a way.

I believe I made the right choice to go there because these last five years have seen a tremendous evolution in the mid-market sector. The most active and dynamic evolution in accessories, of new brands and lots of brands competing for design propositions. A lot of brands were inspired by the famous shows of Paris and producing extremely well-made, almost copies of the Paris fashion shows.

So it was an interesting challenge to keep true integrity at Theory with our own designs and our own way of creating products and quality, in a very competitive sector that is selling clothes to people who don't always know fashion, that do not always know that things are lifted from other collections and that there is probably a copyright ethic behind the products.

Dan Howarth: Would you recommend for young designers to start their own companies and brands, as you did?

Olivier Theyskens: I receive this question a lot and I think I can never answer it the same twice. Especially these days, there is an over offering of new brands. If I put it into perspective of when I started, I think one of the reasons why people supported me a lot was that there was a boring moment between 1994 and 1998, when no new designers were really showing up. When I started it was a moment when Raf Simons started, followed by Jeremy Scott. There was a little group of new stuff showing up, and I think that suddenly people felt excited.

Now in every season and every fashion week, you have 10 or 12 new names. I think it's scary. If someone really talented, in any situation, could be a good star and it might work – if someone is truly strong today. At the same time, a lot of brands that are less prepared, they are facing tough situations with so many new brands.

Dan Howarth: So there's a fear of the industry becoming oversaturated?

Olivier Theyskens: It's saturated. During New York's fashion weeks, you have shows with young designers when you barely have a third of the seats taken by people. It's tough. I know some young designers for whom the PR agency says "you have to do a show" and they will spend all their money on that and it will have zero impact. The people who show up will be the ones that couldn't go to better shows. It's tough, so I think for young designers they have to find more professional support to show that they have the right people on their side. You have to be more professional now when you start than before.

Also, if I compare again to when I started, there was no internet. When I wanted to show my work, I couldn't download pictures of it. I did pictures and I made 50 little portfolios of them and I sent them to a person I knew at a PR agency in Paris. I just asked "who are the 50 most important people in fashion that I should send these pictures to?" There was Isabella Blow and there was Suzy Menkes. These people received this portfolio.

It's not something that can happen today. Professionals in fashion are overwhelmed with the images and websites. It's very tough to get their attention.

Dan Howarth: What might be a solution to this?

Olivier Theyskens: If I was in this situation, I would still be in school. You have to show you're extremely talented, you have to be really strong. There are professionals that can see if you're really able to cut a coat. Also, you have to feel convinced that it's really your thing.

Dan Howarth: And you think it is advisable for students to work with brands to realise that?

Olivier Theyskens: Yeah, but also every summer the schools are difficult. Students don't realise that there are other aspects of the industry where they could find a very strong place. Some of the people doing internships for me, they became super specialist in generating amazing prints or opening a business for trims and providing to all the houses in Paris. But a lot of kids that like fashion could become amazing merchandisers, they could become amazing sales people, they could become PRs or they could work more in ateliers. They don't necessarily need to be the designer. It just depends on each person, and if they have something to express.

I'm seeing a school later today, and I have to think about Louise Wilson. I visited her earlier this year when I went to do a lecture at Central Saint Martins, she was complaining that students had no guts in their creation today and she was bored by everything she saw. I know she was a tough cookie but I think she meant it. She said that too many students coming from comfortable lives came to the school thinking they would get everything they want. She was showing what they were doing and she said that the most creative people in her group might be inspired by a shell or by a tree for their collection, and it's going nowhere. It lacks the guts of the cool guys I had in the 1990s. She was saying that it needs to be shaken up.

I'm not sure how reliable this information was, it might be a little bit true. But when you start you have to shake everything up – you don't necessarily have to be a rebel but you have to do something that moves people, so they get attracted and want to understand what that person is having in his or her mind. That is going to be amazing for the future.