Feature: the office cubicle turns 50 years old this year. Andrew Shanahan investigates the history of the system that revolutionised office design and which, after falling out of favour, is now being re-evaluated.

It was 1965 and George Nelson took to the stage, soaked up the applause and accepted the Alcoa Industrial Design Award for his role on the Action Office (AO-1). The two most surprising aspects of this celebratory moment are that Nelson's design had been a commercial failure and his speech entirely failed to mention Robert Propst.

Propst had invented the Action Office after three years of work at the newly-formed Herman Miller Research Corporation, with Nelson drafted in to give Propst's ideas form. What no one at the awards ceremony could possibly know is that this was a product that would soon take over the world, make Propst an incredibly wealthy man and change the workplace forever.

Put on your party hat, release the balloons: it's the 50th birthday of the office cubicle!

The furniture company Herman Miller was founded by D J De Pree in 1923 and named after the father-in-law who lent him the start-up investment. In nearly a century it has been responsible for many iconic pieces of furniture design. The Aeron Chair, the Noguchi Table and the Eames Lounge Chair are just some familiar names. And yet it's a far more prosaic piece of furniture that remains one of the company's best-sellers, 50 years after its inception.

Although the idea of a piece of furniture that screened off the outside world had been around for decades, with carrel tables and partitions, no one had ever created a system of furniture that allowed employers to format their offices in the way they wanted.

The genesis of the cubicle came from the Herman Miller Research Corporation, a division set up to innovate in all areas and run by Robert Propst, an academic discovered by De Pree who had an incredibly broad range of interests. Over his career he invented everything from an automatic tree-harvester to the first computer workstation. De Pree recognised genius in Propst and gave him a free hand to create whatever he liked.

"Propst was always adamant that Herman Miller did not invent the cubicle," explained Mark Schurman, director of corporate communication at Herman Miller and someone who knew Propst.

"He said it was the marketplace that invented the cubicle. In the 60s when Propst began to analyse the office, he saw the manager in the corner room and the majority of workers at open desks that were arranged in static lines, with very little consideration for any form of privacy, storage or intrusion from telephones. Propst foresaw an explosion in white collar workers and realised that the workplace needed a better solution that would create a healthier, more innovative and more productive workforce."

Propst's research for the Action Office range meant drawing influence from a wide range of disciplines – biology, mathematics, behavioural psychology. To aid Propst with the design elements Herman Miller brought in George Nelson. Nelson was the company's director of design and a huge name in the design world; responsible for seminal creations such as the ball clock and the marshmallow sofa.

Despite both men's obvious talents the creation of the first iteration of the cubicle design was not a speedy process. It took Propst and Nelson three years to create a furniture range which seemed to answer the brief. The culmination of this effort was the snappily titled Action Office 1, or the AO-1. It was a commercial flop.

"AO-1 as you would expect from someone like George Nelson was beautifully designed," explained Schurman. "It featured lovely material selection and lines, but as a result they were rather expensive and they didn't really match Propst's vision, which had been to create this more egalitarian suite of furniture solutions that would be deployed across the mass market.

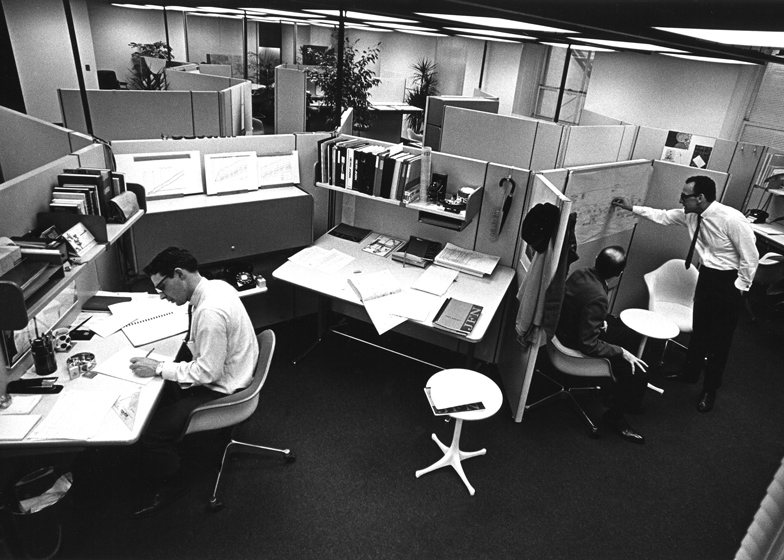

"In AO-1 you can see the beginnings of the ideas that Propst wanted to include such as the vertical use of space with the display boards and screening off workers with shelving units to demarcate separate space but ultimately it was not a success. It was ahead of its time with innovations like the standing desk elements, but what you ended up with in AO-1 was more like an executive office selection."

Despite AO-1 winning the Alcoa award, Propst was adamant that the company hadn't got it right. He knew that what the marketplace wanted was a kit of parts with a wider application, not the finished solution that AO-1 had become. In short, he needed less design and that meant less Nelson.

Propst eventually persuaded D J De Pree to let him have another go. His Action Office II (AO-II) design took until 1967 to arrive in the Herman Miller catalogues but it was everything Prospt believed the marketplace was crying out for. "His vision was this sub-architectural system that would have infinite flexibility and would create that sense of place and purpose for the individual. It had to have the right price point and the ease of configuration and re-configuration," said Schurman.

Propst was right. Action Office II was an instant success and to this day remains one of the company's best sellers. A glowing article from Mid-Western Banker in 1971 sums up the workplace's response to the new innovation, "Banks throughout the country are turning to 'open-planning' – offices without walls – to provide flexibility for dynamic change without sacrificing executive and staff privacy."

To date Action Office has enjoyed more than $5 billion (£3.3 billion) in sales and thanks to a smart contract negotiation Propst gets a royalty of each sale to the present day. Perhaps inevitably, competitors jumped on the bandwagon to create their own versions and as the 1970s dawned the age of the cubicle was under way. By 1978 the AO-II was renamed and became simply the Action Office range.

Cubicle systems remain a best-seller with the modern office according to Mike Philps from Furniture at Work. "Its success is in its simplicity and the power it gives employers. Offices start as a bare room, often with no features or functions attached. Cubicle systems allow them to very quickly and easily create a range of spaces, from meeting areas to individual work spaces, with no building work needed.

"Cubicles have come in for plenty of stick through the years but I think the majority of workers actually like their cubicles – it gives them a degree of privacy where they can concentrate, without cutting them off from the atmosphere of the room."

It's certainly true that in the decades since the Action Office started its dominance of the workplace that they have come in for some criticism. Cubicles have become part of popular culture whether it's cube farms, meerkatting or cartoonist Scott Adams who has made a career of giving the cubicle a comedic kicking.

However, it was the designer of the first iteration, George Nelson, who became one of the most prominent critics of the cubicle. In a letter to the chairman of Herman Miller in 1970, Nelson disassociated himself with the project entirely.

"One does not have to be an especially perceptive critic to realise that AO II is definitely not a system which produces an environment gratifying for people in general," Nelson wrote. "But it is admirable for planners looking for ways of cramming in a maximum number of bodies, for "employees" (as against individuals), for "personnel," corporate zombies, the walking dead, the silent majority. A large market."

Decades have passed and the jury is still out on whether or not the open-plan office that the Mid-Western Banker praised so fulsomely is actually a design conducive to work. The 2013 US Workplace Survey attributed a 6 per cent drop in workplace effectiveness to the open-plan office and research last year stated that 54 per cent of workers would prefer individual offices.

Perhaps much of the confusion lies in the fact that we're not actually using the cubicle correctly. Propst pointed out that actually his original design was based on a hinged system and he thought the best configuration was for two walls positioned at 120 degrees – which mirrored the structure of honeycomb. This gave the worker a measure of privacy and made use of vertical space, but allowed for peripheral discovery. In Propst's view the four-sided cubicle was the worst possible application of his system.

But whether you love your cubicle or hate it, it's fair to say that over 50 years the cubicle has earned the right to be regarded alongside other Herman Miller classics. "We will still be selling cubicle systems when I retire," said Philps. "You might get innovations in technology and working practices but the cubicle is as spritely now as it was when it began 50 years ago, long may it continue."

Andrew Shanahan is a freelance journalist who has worked for The Times, The Guardian and The Daily Mail. He has a new-found respect for his cubicle, but only those at the Propst-approved 120 degrees.