Photo essay: British photographer Alastair Philip Wiper is documenting the construction of a new metro line in the Danish capital – one of the largest infrastructure projects in the city's history.

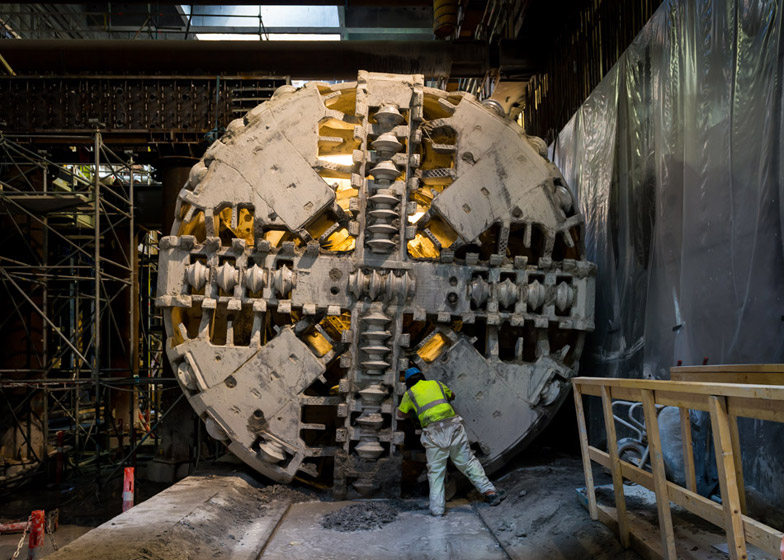

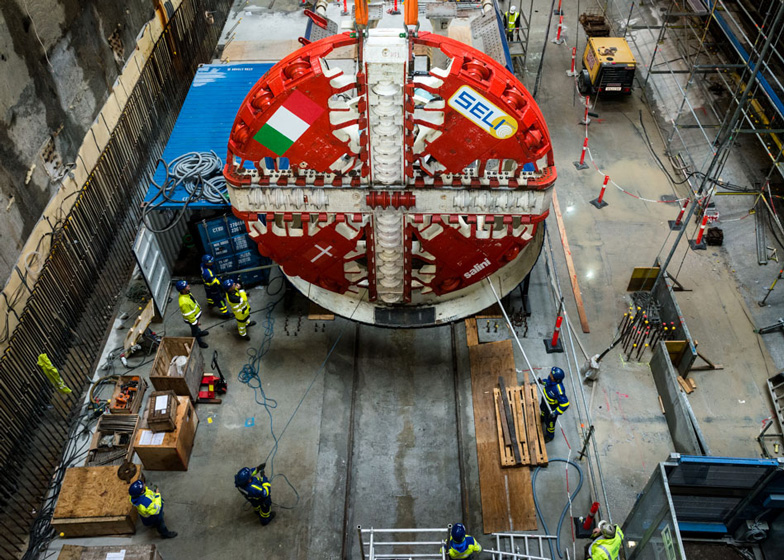

The City Circle Line involves the creation of 17 new stations in Copenhagen, as part of a new ring route expected to replace many of the city's bus services. Wiper visited the tunnels to create a visual record of the construction process, which involves an 800-ton drill.

His photographic series, entitled Building the Copenhagen Metro, focuses on this drill and the hole it leaves in its wake. "The drilling machine builds the whole tunnel as it goes: the drill goes into a wall and leaves a finished tunnel behind it," he explained.

In Copenhagen they are building a huge extension to the Metro. And they are building it right under my house.

I live in a very wonky house. Built as part of a terrace in the eastern part of Copenhagen in the 1870s, within ten years a couple of the houses in the street started to sink at the front and cause the terrace to bow violently outwards in the middle, my house being the epicentre of the violence. The house settled, reinforcements were made, interior doorways righted, and all was well with the world. Tourists walk down my street and take photos of my wonky house. Friends visit and complain of seasickness and disorientation when walking upstairs. I love my wonky house.

The path of the new extension to the Copenhagen metro goes directly under my wonky house. I mean literally, directly underneath. I knew this when I bought it a year and a half ago, when I asked every relevant person I could get my hands on about the potential effects. "They know what they are doing these days, it's really rather clever stuff." Right now, my house, along with all of the others on the street, is covered in little prisms of magic installed by the guys from the metro that monitor any movement of the buildings. I am not sure whether to be scared or reassured by the prisms of magic.

Due to open in 2018, the 'Cityring' will form a circle around the city centre, consisting of 17 stations.

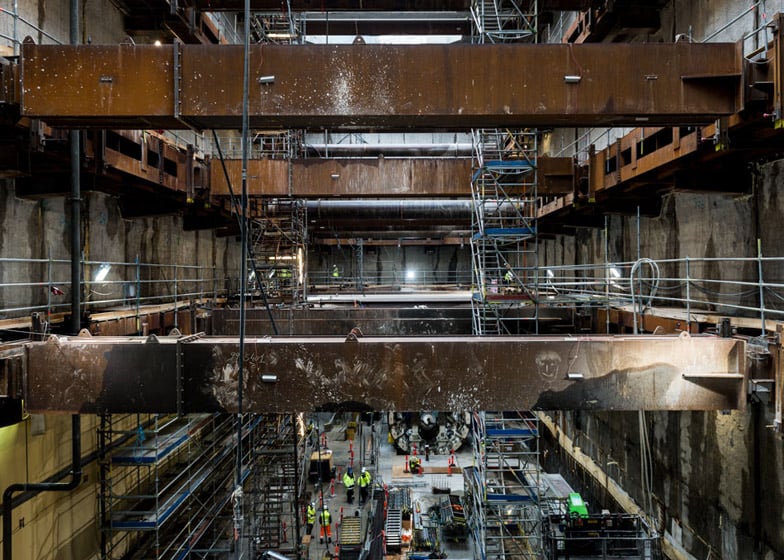

Three million tons of earth will be removed during the excavation and used to build a new area of the city at Nordhavn, and 500 trucks per day will carry the earth away from the sites – traffic lights in the city have been changed to help the flow of extra traffic. It is estimated that the pollution generated by these trucks during the whole construction period will be equivalent to three days normal traffic in the city. Costing an estimated 21.3 billion kroner, the metro is the largest construction project in the city since the 1600s and the line is estimated to carry 240,000 daily passengers, bringing the metro's total daily ridership to 460,000; 130 million people are estimated to ride in 2018. When the new line opens, 85 per cent of the population of Copenhagen will be within 600 metres of a station, including me.

My next door neighbour, Søren, is convinced we are doomed. “It's sinking already. Can't you feel it?” They haven't started drilling here yet.

I've been down there to see how they are getting on. "That drill looks a bit dirtier than last time I saw it" I say, completely pointlessly, while looking at the huge 800 ton machine in front of me. My guide, Jens Munch, tries to feign a smile and says "I think it looked a bit dirtier than last time you saw it about five seconds after they turned it on."

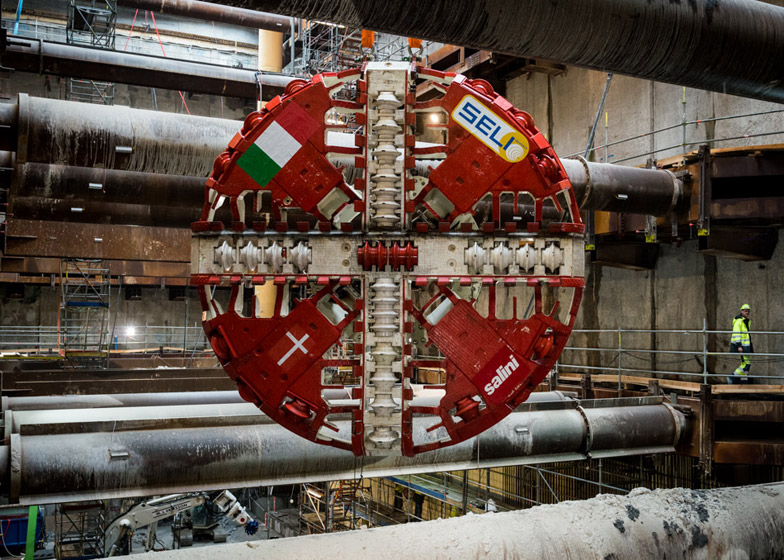

Jens represents the conglomerate of Italian companies that are constructing the metro. I last visited the shaft in the north of Copenhagen in May 2013 before any drilling had begun, on the day that one of the two brightly painted, brand-spanking new drill heads was lowered into the abyss. Since then these 50-ton heads have crawled slowly forward and completed about 1.5km of the 15km route, and we walked that 1.5km taking in a couple of the stations to be.

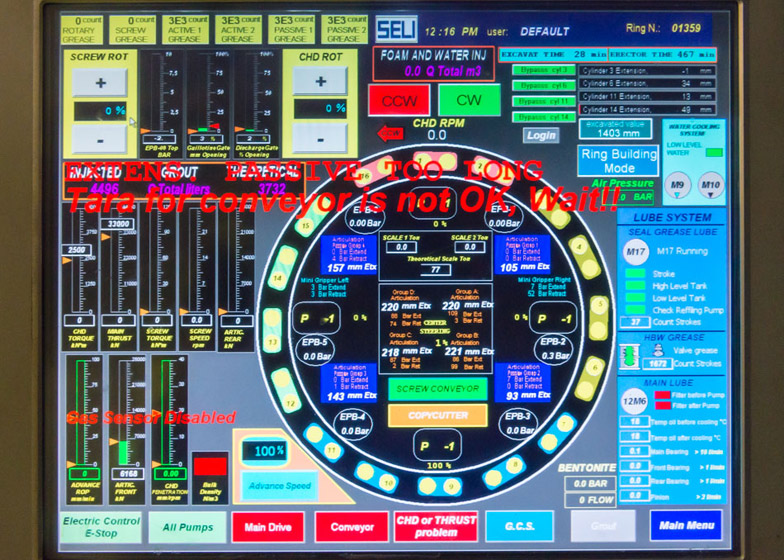

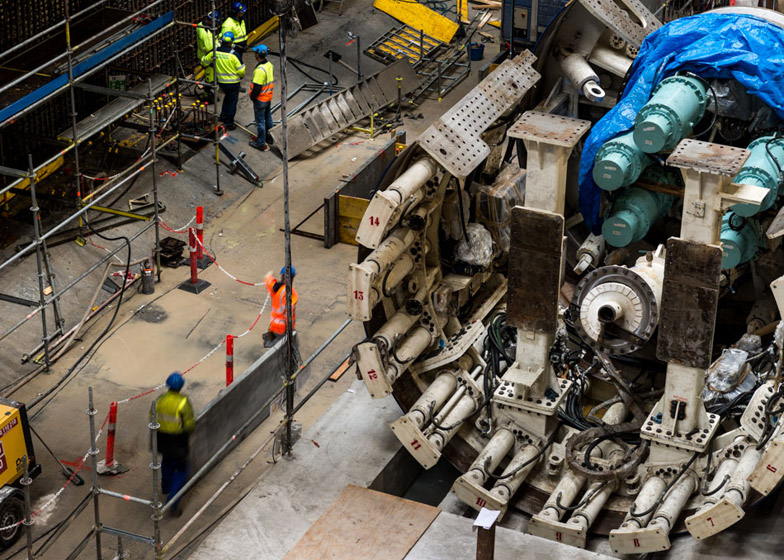

The drilling machine builds the whole tunnel as it goes: the drill goes into a wall and leaves a finished tunnel behind it. It drills through the limestone about 30 metres under Copenhagen, re-enforces the walls and lays concrete sections in rings that have been pre-made in Germany.

Each ring is made up of six identical sections and one key section, and depending on the placement of that key section in each ring the tunnel can be made to turn left, right, up, down, upside down, inside-out and shake it all about. Actually the tunnel dips between stations in order to save energy – the train rolls down from the station, then the momentum carries it back up to the next one. Rather clever.

I remain confident.