Dezeen remembers 2015 Pritzker laureate Frei Otto, who passed away this week at the age of 89, with some of the best projects from his pioneering career as a champion of tensile and membrane architecture and an early adopter of 3D modelling.

German architect Otto died on Monday just days after discovering he had been chosen for the Pritzker Prize, architecture's equivalent to the Nobel. His swooping, tent-like roof structures are often cited by leading architects as a significant influence on their own work.

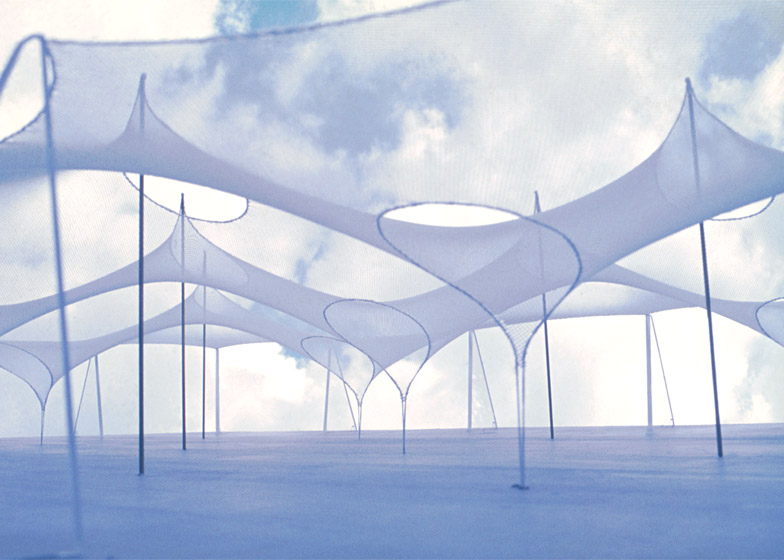

Created by suspending membranes on light steel networks, with column and cable supports, the curving shapes that typified his work were influenced by the forms of tents, soap bubbles and umbrellas.

Otto's approach grew out of an early interest in temporary structures – partly in response to the extreme conditions he experienced in a prisoner of war camp during the second world war and partly due to a limited availability of resources in post-war Germany.

"He was a great, very modest man, and he was soaked through with old-school utopian thinking, the kind of thinking I believe we could all do with a little more of in these cynical days," architecture critic Tom Dyckhoff told Dezeen.

"Whenever I look at the work of the latest architects, be they Hadid, or Heatherwick and Ingels' designs for the Google building, they all just look like Frei Otto's work, such was the prescience of his language of structure and architecture. Would that there were designers today with the same capability to think beyond their own, limited environs, to imagine the incredible and the seemingly impossible."

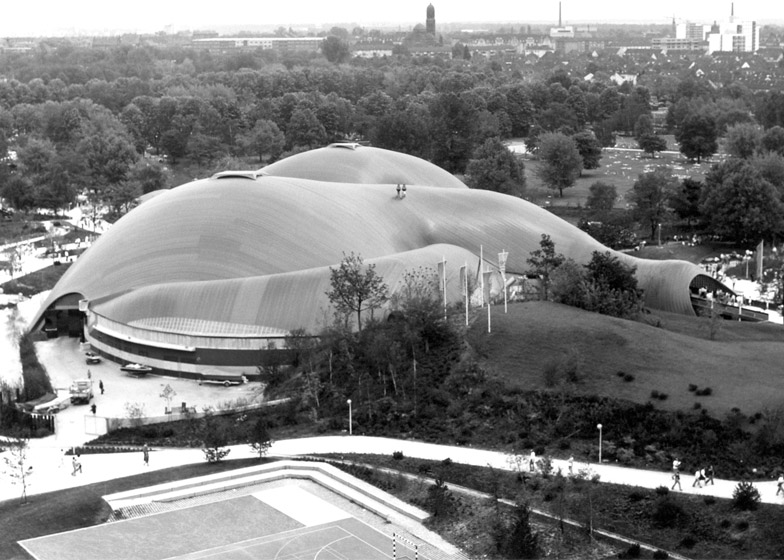

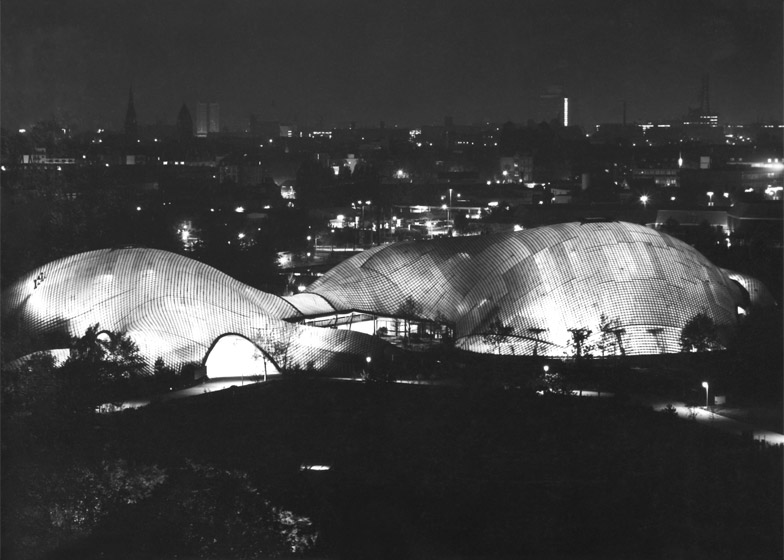

Otto's groundbreaking work with temporary structures first attracted international attention after he was commissioned to create Germany's pavilion for the 1967 World Expo in Montreal, Canada.

Erected in just six weeks, his 8,000-square-metre pavilion was made from a flexible polyester material draped over a net of steel cables, supported by eight irregularly spaced columns and tension cables that created a structure with multiple peaks.

Movie of Frei Otto's cable-net structure development for the German Exhibition Pavilion at the Montreal World Expo, 1967

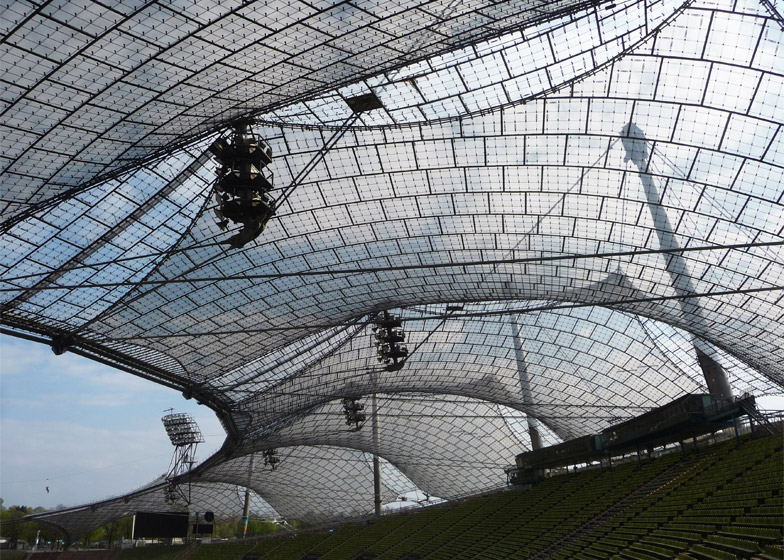

This was followed by his best-known project – the stadium for the 1972 Munich Olympic Games, designed with fellow architect Günter Behnisch.

The transparent tensile roof structure that covered the stands of the stadium featured multiple peaks and was partly influenced by the shape of the Alps mountain range. Supported by columns spaced around the site and tension cables anchored to the ground, the structure was echoed in the glass acrylic roof canopy that connected the surrounding buildings. Otto also created a fabric roof for the Olympic swimming pool.

"Most architects think in drawings, or did think in drawings; today they think on the computer monitor," said Otto in a 2005 interview for architecture magazine Icon with Dezeen columnist Justin McGuirk.

"I always tried to think three dimensionally. The interior eye of the brain should be not flat but three dimensional so that everything is an object in space. We are not living in a two-dimensional world," he explained.

Otto was born in 1925 in Siegmar and spent his youth in Berlin where he was admitted to the technical university to study architecture.

In 1943 his studies were brought to an abrupt halt when was drafted, becoming a pilot in the Nazi Luftwaffe. The following year he was transferred and became a foot solider, but was captured in 1945 and interred in a prisoner of war camp in Chartres, France, where he was the camp architect. This experience led to an early interest in temporary, lightweight structures built using minimal materials.

"Whereas in my youth I made models of classic fighter aircraft, Frei Otto spent his late teens as a pilot actually flying them in action," said British architect Norman Foster in a speech to mark Otto's 80th birthday. "In looking back at his career, there is a similar sense that he has remained one step ahead of most of us."

"It is perhaps his enduring love of flight that has guided his approach to architecture. His has always been an architectural vocabulary inspired by lightness," added Foster.

"This is apparent from his earliest works. The bandstand he designed in 1955 in Kassel, for example, or the wonderful shelter pavilion at Cologne's garden exhibition two years later, demonstrated an extraordinary sense of architectural daring. They showed that architecture need not be burdened by the weight of its own traditions but could instead be free to express itself through a succession of simple but innovative sculptural forms."

After the war, Otto won a scholarship to travel to America, where he studied at the University of Virginia and was exposed to the work of Frank Lloyd Wright, Eero Saarinen, Mies van der Rohe, Richard Neutra and Charles and Ray Eames.

He graduated as an architect in 1952, but returned to the Technical University of Berlin to study for a doctorate in civil engineering and in 1954 he wrote Dan Hangende Dach, or The Suspended Roof, Form and Structure – a dissertation that would go on to be published in three languages.

In 1954 he also began what would become one of his most important professional collaborations. Peter Stroymyere, of L. Stroymeyer & Co – nicknamed "the tent maker" – would help Otto realise the bandstand for the 1955 Federal Garden Exhibition in Kassel.

It was followed by the entrance arch for the same exhibition when it moved to Cologne in 1957, and the Snow and Rocks pavilion at the Swiss national exhibition in Lausanne in 1964. Made from cotton fabric, these double-curved temporary pavilions were created in direct opposition to the neo-classical, monumental styles of Fascist architecture.

"After the war, I [wanted] to find a new way in the future to make a real revolution in architecture, remaking Germany as a peaceful country," Otto told the BBC's Culture Show last year.

He began building complex 3D models to explore and test structural techniques based on creating tension in materials.

Movie of Frei Otto's experiments with soap bubbles at the Institute for Lightweight Structures at the University of Stuttgart

In 1958, he founded the Institute for Development of Lightweight Construction, a small private organisation that he ran alongside his own Berlin studio. In 1964 he became the director of the new Institute for Lightweight Structures at the University of Stuttgart, where he pioneered research into finding increasingly lightweight construction methods often based on mathematical patterns found in nature.

It was through the university that he won the commission to build the 1967 Expo Pavilion that would win him international attention for the first time.

It was also through a commission for the Institute for Lightweight Structures that Otto came to work on the Munich Olympic Stadium, widely considered a triumph in engineering and architecture. The achievement was overshadowed by the massacre of 11 members of Israel's Olympic team.

In 1969, Otto founded a new private studio in Stuttgart, but continued to work as a professor as the university until 1991, when he became an emeritus professor.

"He was a step ahead in pioneering computer-based procedures to determine the shape and behaviour of complex tensile shapes; and he was equally far sighted in seeking structural lessons from biological structures and grid shells," said Foster. "The lightweight tensile structures that he has consistently and so evocatively advocated have achieved greater and greater relevance. He is an inspiration."

Many of his best-known projects grew out of collaborations – particularly his relationship with British engineer Ted Happold, who first began working with Otto while he was at engineering firm Arup and went on to launch his own engineering firm, now known as Buro Happold.

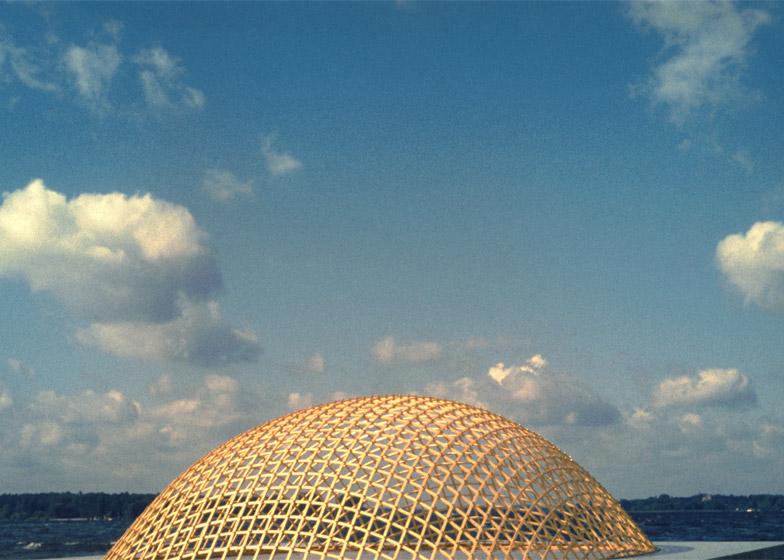

Happold worked with Otto on the structure of the Mannheim Multihalle – a multipurpose exhibition space formed from a shell of timber grids – in 1975. Otto's personal favourite project was the aviary at Munich Zoo, a suspended mesh structure of fine steel cables designed with Happold, which he completed in 1980.

In 1980 Otto won the Aga Khan Award for Architecture with fellow German architect Rolf Gutbrod for the design of a conference centre in Mecca. He won the award again in 1998, this time with Happold, for the Diplomatic Club in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

In 2000, he co-designed the Japanese pavilion for the Hanover Expo with Shigeru Ban, the Japanese architect who received last year's Pritzker Prize. This building used a grid shell system made from recycled paper tubes supported by a timber frame.

In 1982, he won the Grand Prize and gold medal from the Association of German Architects and in 2005 he was awarded the Royal Gold Medal by the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA).

The influence of his work can be seen in projects like Norman Foster's glass ceiling for the Great Court at the British Museum in London, Nicholas Grimshaw's transparent geodesic domes at the Eden Project in Cornwall and Richard Rogers' Millennium Dome.

But despite what this legacy of statement architecture might suggest, Otto gave the impression that he was more interested in ideals than shapes.

"Why should we build very large spaces when they are not necessary? We can build houses which are two or three kilometres high and we can design halls spanning several kilometres and covering a whole city but we have to ask what does it really make? What does society really need?" he asked in his interview with Icon.

"The secret, I think, of the future is not doing too much. All architects have the tendency to do too much."