The curator of a new exhibition of drawings by Scottish architect Charles Rennie Mackintosh has selected six works for Dezeen, explaining how he used his drawing skills as "a valuable promotional tool".

The drawings include an 1897 elevation of Glasgow School of Art, Mackintosh's best known work and "Glasgow's Parthenon", according to curator Pamela Robertson. The school was badly damaged by fire in May last year.

Robertson, considered the world's leading expert on Mackintosh, has just completed a major research project into the architect's work at the University of Glasgow.

"Mackintosh as a person remains elusive," she told Dezeen. "The few documents and recollections that survive show him to have been a man of few words – except when speaking about architecture and design. He was fierce in defending his work."

Robertson has now curated Mackintosh Architecture – the first exhibition of the architect's work in London since 1968 – which runs at the RIBA's headquarters at Portland Place in central London until 23 May.

It includes 60 of Mackintosh's original drawings, watercolours and perspectives, spanning his career and revealing the development of his unique architectural style.

The drawings showcase "Mackintosh's exceptional draughtsmanship," Robertson said, and were often produced as publicity material for the architect and his firm. Mackintosh was an employee of Glasgow firm Honeyman and Keppie from 1889, working his way up from draughtsman to partner before leaving in 1913 to launch his own practice.

Included in the exhibition are Mackintosh's designs for the Liverpool Cathedral competition, which he lost to Giles Gilbert Scott. Roberston described this as "a bitter blow" and explained that his wife, designer Margaret Macdonald, believed that the architect's originality had counted against him: "[She] wrote to a friend saying, 'a great great pity about the Cathedral but only what one must expect. In architecture, originality is a crime.'"

Almost all of Mackintosh's built work – including the Glasgow School of Art, which took over 12 years to complete – was created in an intense period between 1896 and 1910. By 1920, his career was "effectively over," said Robertson. He moved to France with Macdonald in 1923 and concentrated on painting but later became ill, forcing the couple of the return to the UK. He died in London, aged 60, in 1928.

Many of the drawings on show at the RIBA are early and late Mackintosh designs that were never built, including early competition entries, "ideal" schemes and projects constrained by client's wishes.

Despite dying in relative obscurity, Mackintosh has become one of the best-known late 19th and early 20th century architects. The Glasgow School of Art, was voted the best British building of the past 175 years in 2009, but was damaged by fire last May. Earlier this week, Scottish firm Page\Park was awarded the job of restoring the building.

Below, Pamela Robertson writes about six key drawings from the Mackintosh Architecture exhibition:

The Glasgow School of Art: north elevation, March 1897

The Glasgow School of Art is acclaimed internationally as Mackintosh's masterpiece of architecture and interior design, for its masterful handling of space and light, and its inventive detailing.

Built in two phases, between 1897–9 and 1907–9, it spans his architectural career and remarkably was the only competition he won. This elevation shows the principal north elevation and the vast windows which light the main studios, the heart of the building.

Mackintosh's design delivered a highly practical and efficient building which continues to serve its purpose well, training internationally acclaimed artists and designers. Tragically damaged by fire in 2014, it is currently shut down, but plans are underway to resurrect this astonishing building, Glasgow's Parthenon.

Image courtesy of Glasgow Life (Glasgow Libraries: Glasgow City Archives) on behalf of Glasgow City Council

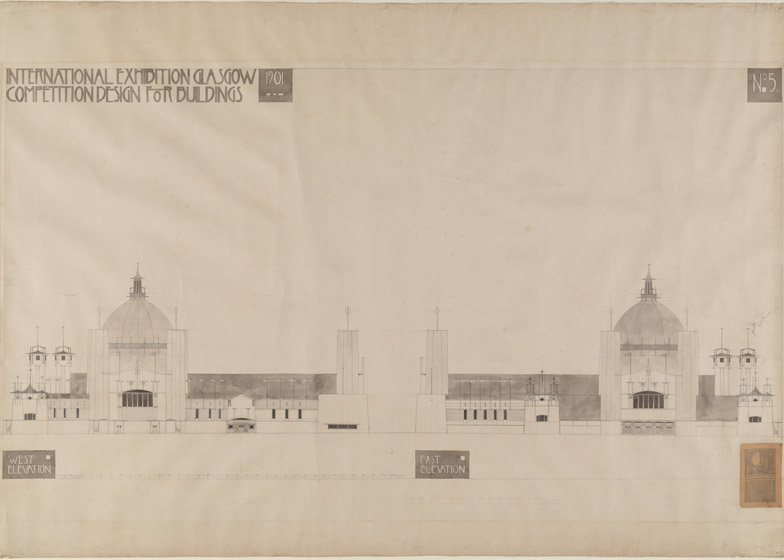

Glasgow International Exhibition competition design: east and west elevations of industrial hall, 1898

International exhibitions were an important means of a city demonstrating its success and establishing its world-class status. Not to be outdone by London, Paris, or Chicago, Glasgow held two. The first in 1888 and the second in 1901. Mackintosh entered the competition to design buildings for the latter. The temporary nature of such buildings and their role as showpieces allowed the designer a large degree of creative freedom.

Mackintosh's domed Industrial Hall appears plain, but notice the unorthodox detailing, neither classical nor Gothic, and the variety of non-traditional window shapes. Mackintosh's design was unsuccessful; instead a fanciful 17th-century Spanish-inspired confection by Scottish architect James Miller was selected.

Image courtesy of The Hunterian, University of Glasgow

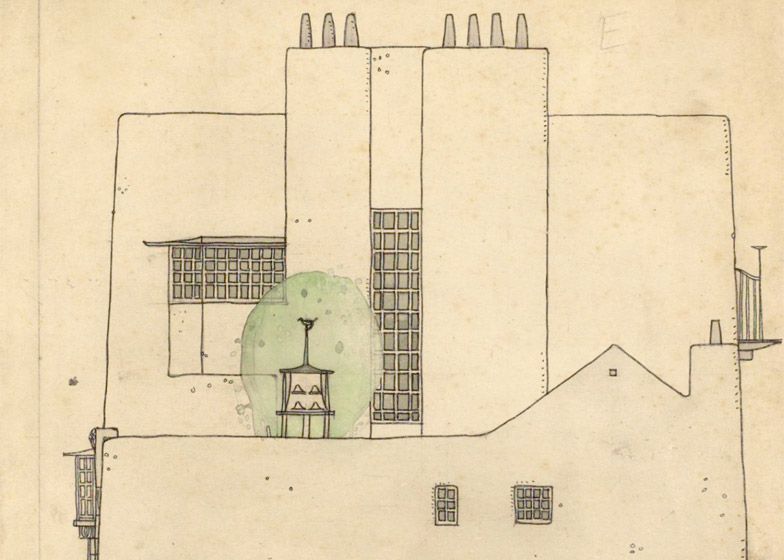

Artist's house and studio in the country: north elevation, 1899–1900

Around 1900 Mackintosh prepared designs for a companion pair of houses, for an artist in the town and the country. This elevation shows the garden wall of the latter. Neither scheme was built.

They are generally viewed as schemes prepared before his wedding in 1900 to the designer Margaret Macdonald, as his vision of an ideal setting for the artist-couple. In fact Mackintosh never had the opportunity to build a house for himself.

The schemes are an important landmark in Mackintosh's career, as he develops the radical paring away of superfluities which had appeared in his Glasgow International Exhibition buildings and School of Art designs.

Image courtesy of The Hunterian, University of Glasgow

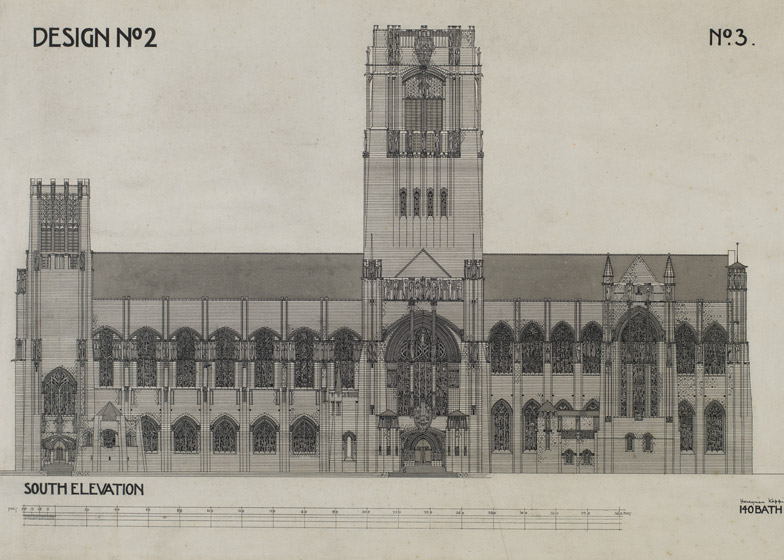

Liverpool Cathedral competition design: south elevation, 1901 or 1902

Liverpool Cathedral was one of the big architectural prizes of the 20th century. Mackintosh's firm [Honeyman and Keppie] entered two designs, one of which was by Mackintosh.

Mackintosh's imposing scheme presents his individual version of Gothic, incorporating towers, soaring buttresses, and traceried windows. But notice the inventive and complex patterns, unique to each window, which owe more to Glasgow's version of Art Nouveau than to the Gothic.

Mackintosh's failure to win – the commission went to the young Giles Gilbert Scott – was a bitter blow. His wife, Margaret Macdonald, wrote to a friend, ‘a great great pity about the Cathedral but only what one must expect. In architecture, originality is a crime.'

Image courtesy of The Hunterian, University of Glasgow

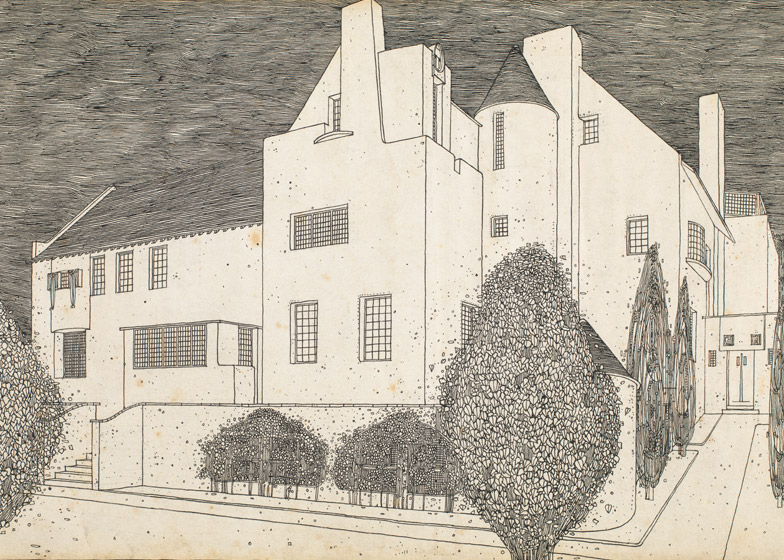

The Hill House, Helensburgh: perspective from the south west, 1903

The Hill House is Mackintosh's domestic masterpiece. Built for the publisher Walter Blackie and his young family, it is sited in Helensburgh and commands panoramic views south over the river Clyde. It sits like a 20th-century Scottish tower house, with its roughcast walls, slate roof, asymmetrical disposition of windows, picturesque roofline, and lack of historic ornament.

Mackintosh's perspective showcases the house, setting its white mass against a striated dark sky and embellishing the foreground with flourishes of trees. The drawing also showcases Mackintosh's exceptional draughtsmanship. Perspective drawings such as this were a valuable promotional tool, created for publication and exhibition.

Image from private collection

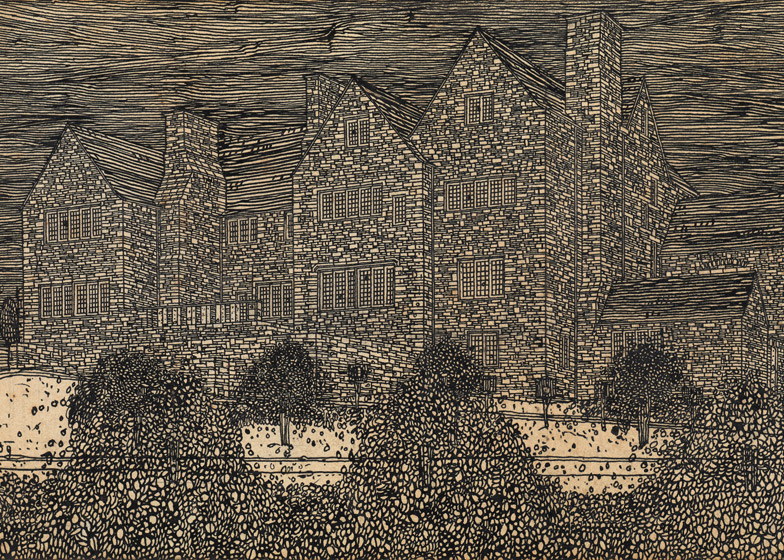

Auchinibert, Killearn: perspective from the south west, by 1908

This intensely worked perspective drawing – notice how every leaf in the foreground bushes has been individually detailed – is Mackintosh's last perspective and records his last house. It marks the beginning of the downturn in his career, which was to be effectively over by 1920.

Auchinibert was built for Francis J. Shand, manager of Nobel's explosives, Glasgow. It is an unexpected house in that it does not conform to Mackintosh's known aesthetics as seen at The Hill House. Rather it is modelled on the proportions and detailing of English houses of the 16th and 17th centuries, a pragmatic response by Mackintosh to his client's wishes.

Image courtesy of The Hunterian, University of Glasgow

Mackintosh Architecture is on show at the RIBA, free admission, until 23 May.