Architectural photography was "staged and contrived" before digital, say Hufton and Crow

Interview: Nick Hufton and Allan Crow are the photographers of choice for designers including Zaha Hadid and Thomas Heatherwick. With their first exhibition now open in London, the pair spoke to Dezeen about the advantages of digital photography, and why retouching is just as important as shooting (+ slideshow).

The Hufton + Crow pair, aged 43 and 39 respectively, grew up together in Macclesfield, northern England, before moving to London. Both trained in analogue, using the large format camera favoured by many architectural photographers, but switched to digital as soon as the opportunity arose.

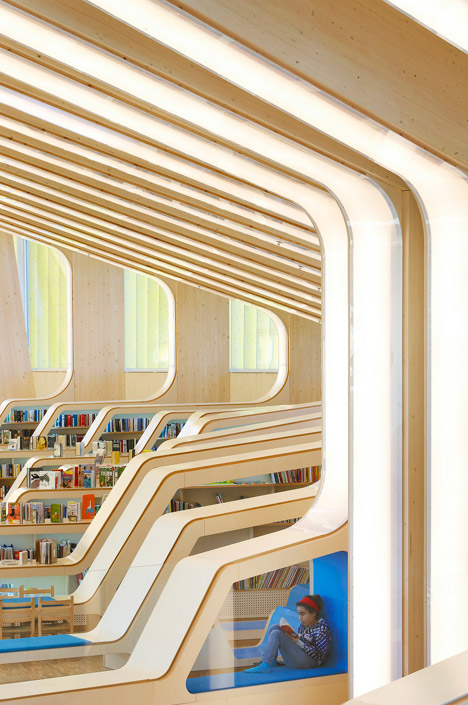

The nature of digital photography made it possible to stitch together several images to show wider views, or to combine a series of moments into one. It marked a turning point that has led to commissions from some of the world's top architects.

"It was so slow with the 5x4, everything was staged and a bit contrived," Crow told Dezeen. "You'd have to have people in positions and you'd have to direct everybody at the scene, whereas the 35mm allows us to capture things in the moment."

They describe their technique as "a package" that involves as much consideration at the shooting stage as during the retouching.

"With the old camera system you took a picture and that, largely, was the image you got," said Crow. "But now you're almost collecting data on site. You're imagining what the shot will be."

"It becomes a storytelling tool," added Hufton. "Because you've got the speed and the flexibility, you can piece your big story together at the end. You can show people a building without them actually going there."

The lighter equipment for digital format afforded more opportunities to work abroad, prompting Hufton and Crow to self-fund several of their own shoots. A series of uncommissioned image sets caught the attention of Zaha Hadid's firm, leading to an ongoing collaboration.

In late 2013, the pair travelled to Baku, Azerbaijan, to document Hadid's Heydar Aliyev Centre. One of their images was later named photograph of the year at the 2014 Arcaid Images Architectural Photography Awards.

"For every job we try and tell the story in about 30 images – everything from the construction details through to the dawn/dusk shots, night shots, and people moving around the space," said Crow.

Unlike photographer Hélène Binet, who recently told Dezeen she found drone-mounted cameras "a bit of a shock", Hufton and Crow have also been experimenting with using unmanned aerial vehicles on shoots. "I think that's about to explode," said Hufton. "I think aerial photography from a much lower level than helicopters is going to be a massive advantage if it can be properly recognised."

The Hufton + Crow exhibition is on show at the William Road Gallery, part of the London office of John McAslan + Partners, until 17 April.

Here's a full transcript of the interview:

Amy Frearson: How did the two of you end up working as a partnership and what are the benefits?

Nick Hufton: I moved to London in 1996 to assist a photographer called Chris Gascoigne. We worked together for three and a half years on some really cool architectural projects. I learnt how to shoot with 5x4, lighting, flash, you know, shooting with the dark cloth, and that kind of thing. Then, it was about 1998, Al came down for the weekend to assist me with a couple of my own jobs.

Allan Crow: After that, I didn't go home. I'd just finished university and was looking for something to do, to be honest. After a few shoots with Nick, I instantly loved it. So then I filled Nick's boots by assisting Chris, and I did that for about three or four years. And then, like all good decisions, we were in the pub one day and we just decided to team up and work together. That was about 2003.

I think the advantage of us working together is the ability to share knowledge, to share what works and what techniques are best. Looking at each other's work inspires us both to push harder.

Nick Hufton: There's also the flexibility to cast another eye on things. Say if shots need to be refined or finely tuned with retouching, it's really good for us both to have a chat about it first. Often those changes allow a set to become five per cent better than it was, and those little percentages do make the difference.

Amy Frearson: Can you describe your photographic approach?

Allan Crow: We started off using 5x4, but when the digital revolution came around we jumped on it. There was maybe a tendency from some of the older photographers to stick to 5x4, and to see 35mm digital as a less professional setup. But we decided that the files were good enough, and as soon as the Canon 1DS Mark 2 came out we just switched over. From that point on we started doing really well – it was a real turning point.

Amy Frearson: What changed?

Nick Hufton: For the first time we could get abroad quite easily and cheaply. Rather than checking loads of bags and boxes on to the planes, it was literally just a rucksack and a tripod.

Allan Crow: And also, it was so slow with the 5x4. Everything was staged and a bit contrived. You'd have to have people in positions and you'd have to direct everybody at the scene, whereas the 35mm allows us to capture things in the moment. So instead of photographing things looking a bit staged and obvious, it became more about capturing everything that was happening, with the architecture as a backdrop.

The focus became more about the people. Obviously you can't always have people but we try and capture –whether it's someone on a skateboard or someone walking by with their dog – anything to just show the human interaction with a building, which is what I think makes our images more interesting to look at.

Nick Hufton: The other attribute is the ability to retouch a lot more with digital. Whereas with 5x4 we'd have a dog-eaten transparency that we'd scanned, which would have a lot of the nice elements taken out of it, but with digital you've got a lot more leeway with the retouching at the raw stage to jiggle about and stitch things together. You can blend light and dark shots together, blend people into position, and you can blend the moment as well.

I think that's a key drive to our style – not just worrying about the shooting stage, but looking at it from the re-touch stage as well, so the whole thing comes together in a package at the end.

Amy Frearson: So retouching is now just as important as shooting?

Allan Crow: Yes. With the old camera system you took a picture and that, largely, was the image you got. But now you're almost collecting data on site. You're imagining what the shot will be and you set the camera up and you're taking multiple exposures, and shifting the lens round, and stitching images together with an imagined finished image in your mind so that when you get back to the studio you know that you can create the image with the data you've collected on site.

Nick Hufton: It becomes a storytelling tool. If you did it on 5x4, you'd be harder pressed to get that story together but because you've got the speed and the flexibility with the 35mm you can piece your big story together at the end. So, if it's a wicked project with amazing light and lots of stuff happening, you could end up with maybe 40 shots in a day that will give you everything. You can show people a building without them actually going there.

Amy Frearson: Do you often stitch images together to make spaces appear busier?

Allan Crow: Quite often there's nobody around and by being patient you can capture people as they walk through the space naturally but it's sometimes easier just to add more people in to give the impression that it's busier. So you are manipulating the image slightly, although it's still reality – it is what's there. But you're often just enhancing it a bit so that people are in exactly the right positions, which is key.

For example, the image that won the Arcaid Images Architectural Photographer of the Year 2014 Award shows a person standing at the top of stairs. There were people moving round all the time, and we shot people in so many different positions, but once we got back and looked through them it was almost like looking at negatives. You choose the right person who is in just the right position because that's the most powerful way of describing the architecture. It's the moment.

Amy Frearson: Can you tell me a bit more about that shoot, the one for Zaha Hadid's Heydar Aliyev Centre?

Nick Hufton: It's one of the rare projects we went to shoot together. Generally we go on our own and just crack on and shoot it from a one-person perspective, but because it was such a huge project we needed to cover a lot of ground. We were there for two days and we hardly saw each other. One I was inside, maybe I was shooting like an auditorium shot and…

Allan Crow: …and I was on the roof somewhere.

Nick Hufton: We were very lucky there with the light on that trip. We got some good stuff.

Amy Frearson: Can you tell the difference between each other's shots, or have you evolved an identical style?

Nick Hufton: It is almost a mirror. If anything I'd say perhaps Al would maybe do a looser reportage style sometimes than me, but perhaps on different projects. Different projects complement different fineries.

Allan Crow: The other thing that's really key to what we do is that for every job we try and tell the story in about 30 images – everything from the construction details through to the dawn/dusk shots, night shots and people moving around the space. All these things put together are the things we've worked out together over the last 10 to 12 years.

Amy Frearson: You said before that you were quick to move to digital. What about other new technologies, like drones?

Nick Hufton: We have a drone actually, a baby drone, but we've invested in a new drone that we test flew the other day. I think that's about to explode. As long as you're getting a licence and going through the proper channels, I think aerial photography from a much lower level than helicopters is going to be a massive advantage if it can be properly recognised. Obviously shooting from a helicopter is amazing as well, but it's less accessible. We recently shot a building from inside with a drone, and we've got a couple more coming up. We're also about to shoot the inside of a velodrome, with lots of cyclists volleying round and round. For us, drones are definitely the way forward. We're just getting our heads around it all.