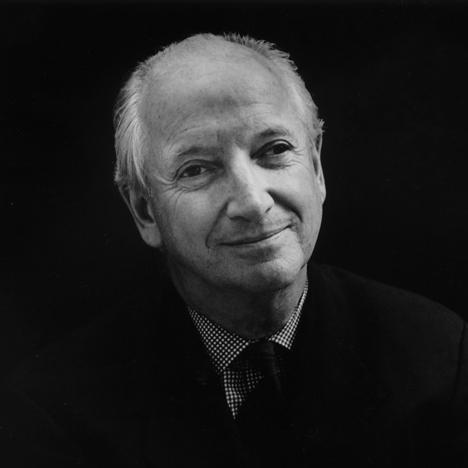

Lyndon Neri and Alberto Alessi have paid tribute to Michael Graves, following a memorial service for the influential American architect who died last month (+ interview).

Graves, who died in March at the age of 80, was best known for his Postmodernist-style architecture and design projects, including the Portland Public Services Building in Portland, Oregon, and a range of implements for Italian kitchenware brand Alessi.

A memorial service was held at Princeton University on 12 April and was attended by his family and colleagues from his firm Michael Graves Architecture and Design as well as former students.

Lyndon Neri, co-founder of Shanghai-based architecture and design firm Neri&Hu, worked for Graves for 10 years and described him as a "father figure" who subverted the stereotype of the prima donna architect.

"He was very important in architecture because he was not just practicing architecture with a big A," Neri told Dezeen.

"He always believed – quite contrary to what most architects think – that we're designing for the masses. Initially we thought it was just a marketing gimmick, or perhaps it was just a strategy on his end to get more design products, but he really believed it."

Neri said Graves' work for cheaper brands like Target was a sign of his belief in democratic design.

"He pushed it to another level by working with Target and having to deal with lower-priced objects and making them work," said Neri. "A lot of people probably think he sold out, but in many ways he made design accessible to the everyday."

"He's always considered a Postmodernist architect, but I think he hated that label – he wanted to be considered a good architect or designer," added Neri.

"I think a part of him didn’t really believe in the modern tenet that he was part of and I think it was a struggle for him. He once told me: 'Lyndon, if my project for my client is very different from the design of my house then I'm really not true to myself, I'm not being authentic.' So there was something about Michael that was very genuine."

Alberto Alessi, founder of the Italian homeware brand, said that Graves was a "design hero" who had the rare talent of combining high-quality design with an understanding of public taste.

"I have worked with hundreds of architects and designers in my career, but I've met really few able to get in tune with popular taste," Alessi told Dezeen. "It's a kind of mystery. Putting together these two extremes, being high-quality design but also being understood, is a talent. With Michael it was a natural talent."

Among the designs Graves created for Alessi was the 9093 kettle, which remains in the firm's top 10 bestsellers 30 years after it first went into production. Alessi said the kettle's bird-shaped whistle was the brand's most stolen product around the world.

To mark the anniversary of the design and pay tribute to Graves, this summer the brand will launch a version that replaces the bird with a pre-historic reptile designed by the architect before his death.

"He brought something new, something that was never done before," said Alessi. "He explained that it was acceptable, even on a cultural point of view, the fact of being ludic, of being Postmodern, of bringing a completely new hybrid language instead of the very purist language of, for example, Sapper."

Alessi and Neri were speaking to Dezeen in Milan during last week's furniture fair, which saw the launch of two new lighting designs by Graves for American company Ilex.

Read the edited transcript from our interview with Lyndon Neri:

Marcus Fairs: Lyndon, you worked with Michael Graves, first of all how did you come to work in his office?

Lyndon Neri: It was interesting because Rossana [Hu, Neri's partner] was going to school at Princeton and I had just graduated from Harvard. We were in Princeton and it was obviously the only choice, or the one that was important to me. During that time his was the one practice that was doing interesting work.

Marcus Fairs: And what era was that?

Lyndon Neri: That was 2002.

Marcus Fairs: As a young architect what was it about Michael that stood out? Why had he been important in architecture?

Lyndon Neri: I think he was very important in architecture because he was not just practicing architecture with a big A. He was really serious about interiors and was always telling us that the architecture is so powerful, but if you enter that door and the interior is not taken care of, then the spatial experience is not there. He'd push it even further by developing the notion of product design and even graphic design, so the whole idea of interdisciplinary practice was very much real. That definitely had a big influence for me and Rossana.

Marcus Fairs: Because you’ve done a lot of product design as well…

Lyndon Neri: Correct. That was ingrained in the practice. When you're working at Michael Graves it's not just purely architecture, you have to deal with interiors and obviously the furniture that is in the space.

Marcus Fairs: It's interesting because when he died, the piece of work of his that became the icon of his life was the kettle for Alessi rather than any of the buildings.

Lyndon Neri: I appreciate what Michael had, his conviction of celebrating the very simple things. And he always believed – quite contrary to what most architects think – that we're designing for the masses. Initially we thought it was just a marketing gimmick, or perhaps it was just a strategy on his end to get more design products, but he really believed it. He was not just working for Alessi, he pushed it to another level by working with Target and having to deal with lower-priced objects and making them work. A lot of people probably think he sold out, but in many ways he made design accessible to the everyday.

Marcus Fairs: When I was a design student he was part of the Postmodern movement. But he actually shifted through different styles. What do you think his legacy is in terms of a stylistic movement?

Lyndon Neri: He's always considered a Postmodernist architect, but I think he hated that label. He wanted to be considered a good architect or designer. He was part of the New York Five, but I think a part of him didn't really believe in the modern tenet that he was part of and I think it was a struggle for him. He once told me: "Lyndon, if my project for my client is very different from the design of my house then I'm really not true to myself, I’m not being authentic." So there was something about Michael that was very genuine. I worked with him for 10 years and having travelled with him I saw that consistency with his belief and with what he was doing. Often architects are really avant-garde with a project they do with clients, and they are really experimental with clients, but when they go to their home it's just a Classical or a Neoclassical building, with spaces that are classically proportioned.

Marcus Fairs: What projects did you work on when you were working with him?

Lyndon Neri: Rossana was there for four years – I was there longer, 10 years. I started with smaller projects. Actually when I started I worked for the international finance corporation, IFC they call it, and I worked on a number of projects and I would obviously be exposed to a lot of the product design that was all over the office. But eventually I got to do a lot of the bigger towers that he was doing in New York, and obviously a lot of the Asian projects.

Marcus Fairs: What was he like as a person?

Lyndon Neri: I always told people that he's almost like a second father to me. Once you got to know him you would see the generous side of Michael. He was very kind to clients. People often think an architect of that caliber will be quite a prima donna, but he would go in and when a client didn't like the scheme he would say "there's a million ways to skin this cat," and he's the same way with the people working under him. Almost paternal. So when we would travel, there was always time to go shopping, there was always time to go to museums, and it wasn't always just about work – he did care.

I remember him coming to Shanghai last year. When I heard of him passing away it was extremely emotional. He'd been in a wheelchair for ten years and he hadn't been back to China, but he finally came back to see a lot of the projects that he'd done. We set up this dinner, and we spent three hours talking and at the end he's like: "You know Lyndon, I’m really proud of what you've done. I'm not just saying this but you've really pushed the boundary of what my conviction was, and it's part of yours now, this sort of interdisciplinary that design is not just an exclusive, it's not just for an exclusive club."

That meant a lot to me. That's almost a blessing, coming from someone who expected a lot. Obviously our work is very different, but the essence of what we're doing is very similar.