New York 2015: in the next of our series of interviews with New York designers, David Weeks explains how he kickstarted the city's vibrant design scene – and why he doesn't want to be typecast as a lighting designer (+ slideshow).

"Lighting was just an opportunity that was there at the time," said Weeks, 46, who built his business around lighting design after realising he didn't have the space to pursue his interest in furniture.

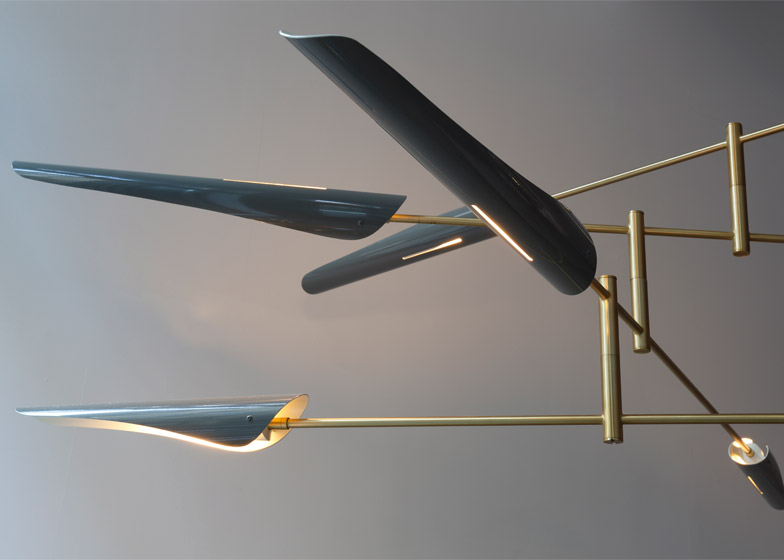

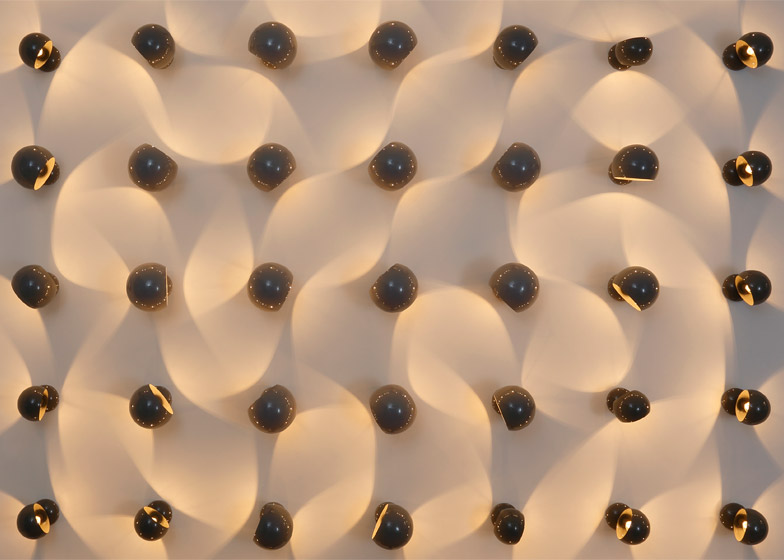

Despite the relatively easy money in lights – some of his pieces, including polished metal chandeliers with mobile arms and glossy domed or cylindrical shades, sell for over $15,000 – Weeks became frustrated.

"I met people who would say: 'I thought you'd be an older French man.' Now the same people will say: 'Oh you're the lighting guy, I've heard about that lighting guy,'" said Weeks, speaking to Dezeen at his New York studio.

"I don't want to be the lighting guy. I appreciate it, but I wanted to be more than that."

Over the past five years, Weeks has started exploring other types of product design, with sofas and chairs as well as a series of wooden articulated toys. The best known of these are the Cubebots, robots that fold into square blocks for storage.

"The [toy] animals were the first cry for help, the first opportunity to really create an aesthetic and apply the same quality and level of detail that is in the lighting, but in a more accessible way," explained Weeks.

The success of the toys generated what Weeks describes as a "mid-life creative crisis".

In 2012, his studio presented a giant version of the Cubebot for its first appearance at the Milan furniture fair as a statement of intent.

He stopped selling his work through the showroom of furniture gallerist Ralph Pucci and last year opened his own space in Manhattan's Tribeca district.

Weeks started his career nearby, working with jewellery designer Ted Muehling at his Canal Street studio. Muehling's habit of giving his staff books on European furniture designers for their birthdays sparked a desire to change disciplines.

"I was interested in furniture but it was a really practical decision," said Weeks. "Furniture was too big for the studio I had at the time, and I'd done a lot of metal work for people."

"I made as many desk lamps as I could and brought those to ICFF. I had one shelf next to the bathroom. Whatever it was that was in those pieces, it struck a chord with a lot of people."

His relationship with Pucci helped him command higher prices and build his company, producing his designs in-house. But he still applies the techniques he had learnt under Muehling in his lighting.

"To me it is jewellery for the home," he said. "All the processes that we would employ at Ted's – sanding shapes and blazing and plating – this would inform the entire process."

"That is a big aspect of the whole aesthetic that exists in New York now. So many of us are doing the same sort of finishes, whether it's brass antique or gold plated."

Weeks is now widely considered the father of New York's "exploding" lighting scene, with many of its biggest stars, including former colleague Lindsey Adelman, sharing a similar business model.

"For so long there was no competition, so there was always opportunities," said Weeks.

"It is funny to see the scene develop and know that what you stumbled on 25 years ago was the blueprint for so many people now."

Read the edited transcript from our interview with David Weeks:

Alan Brake: Lighting was one of the big trends at Design Week and has been an emerging trend for the last few years here in New York. Would you say you were the progenitor of that?

David Weeks: Yeah, I was. It is funny to see the scene develop and know that what you stumbled on 25 years ago was the blueprint for so many people now.

I worked for Ted Muehling before then. For every birthday party at his space, Ted very generously gave you a beautiful design book – it was these access points like Prouve or the French designers. And that was the starting point, because I'd studied painting and sculpture in school so I didn't have any design background.

I was interested in furniture but it was a really practical decision. I didn't feel comfortable doing jewellery because I didn't want to step on Ted's toes. Furniture was too big for the studio I had at the time, and I'd done a lot of metal work for people. Lighting was a much more accessible and manageable thing.

I took time off from Ted and with the amount of materials I had and the tools I had, I made as many desk lamps as I could. I came up with about 12 or 15 different styles and brought those to ICFF. I had just one shelf next to the bathroom. Whatever it was that was in those pieces, it struck a chord with a lot of people. Just the nuance and the elegance.

Alan Brake: Is there still a relationship between your work and jewellery?

David Weeks: To me it is jewellery for the home in a sense. All the processes that we would employ at Ted's – sanding shapes and blazing and plating – this would inform the entire process. In a way that is a big aspect of the whole aesthetic that exists in New York now. So many of us are doing the same sort of finishes, whether it's brass antique or gold plated.

Alan Brake: How did you turn that first show at ICFF into a business?

David Weeks: It wasn't a big plan from the beginning, there was no business model or anything specific that I was following at the time. An architect – Robyn Owen – saw those desk lamps at ICFF, and she asked me to create a large-scale fixture for an elevator shaft on Wall Street. That was a three-storey-high space that needed to be filled with a fixture.

She was a great champion. That job was amazing. One of the tricks to that was that you had to build the entire thing before you drilled the balance point, that way you don't have to put the light bulbs in the heads to actually have it balance properly.

Alan Brake: And how do you do that? How do you calibrate that without assembling it?

David Weeks: You don't – you make the entire thing, and then you pull the wires back and you drill the hole. To go to that extreme... you kind of get rid of a lot of the competition right there.

One things about my work is that I want it to be as honest as possible and not hide the pieces with decorative elements. So it is what it is, the detail is right but there's not a lot of flourish.

That mobile, we made that initially and it was a big deal getting it over there and I set it up and re-adjusted it, and then I made several but I would always deliver them and install them on site.

Then when we joined the Ralph Pucci showroom, we started just shipping them out wrapped up in bubble wrap. And I thought for sure I'd be hearing some complaints from people who couldn't assemble it and make it look right, but if you keep it all wrapped up and hang it to the ceiling and then remove all the bubble wrap, it unravels and just sits properly in the room.

Initially all of it was one-to-one, it was me to a customer. I would make something for their house and I would bring it to their house and I would install it. And that model evolved into the Ralph Pucci model. His knowledge of moving large-scale, incredibly expensive furniture kind of opened up the opportunities for us to sell across the country.

Alan Brake: And what sort of scale are we talking about in those years? What sort of volume of sales?

David Weeks: It was like $2 million – that kind of goes between what we made and what Ralph made, so it's sort of a relative number. But it created the engine that is still running today.

For so long there was no competition, so there was always opportunities. Then Lindsey came to work for me in 1998. She worked with me for about a year. I didn't have the means to keep full-time employees, so we decided to start Butter, and then that ran its course and Lindsey moved on to do her thing.

The business just evolved. When I was running a business, I was always apologetic about asking for too much money, it never felt comfortable for me to charge what I needed to charge, but Pucci changed that entirely.

I actually feel like that created the whole market, because the whole strength of this market is the scale and the numbers and the margins. If you're competing with a Nelson Bubble at Design Within Reach then there's no point, but if you're competing with Roll & Hill for a $15,000 fixture, it's well worth the effort to make it and deliver it.

Alan Brake: What is it about lighting that translates into those sorts of numbers?

David Weeks: A couch from B&B Italia can cost as much as $15,000, and it takes a lot of work and a lot of materials and then you have to bring it over to the US. A very thin wiry elegant fixture can cost as much and still find its audience and find the buyers, because it is that piece of jewellery and that kind of wow moment as you walk into someone's home. It can be spectacular and it can be almost nothing.

Furniture has a bit of a blue-collar aspect to it – you have to sit on it whilst you eat – it can't be sort of ephemeral and crazy. But lighting gives you the opportunity to play with things, and play with space in a way that you can't with other furniture.

Alan Brake: Why did you decide to start your own showroom and sell your pieces directly?

David Weeks: I think it started with a mid-life creative crisis. Pucci was great, but I had to sit back one day and think is this it? Is this what I'm going to do for the next 20 years?

I'd started doing toys and other products – furniture, rugs – and the fact that I couldn't connect all those dots was one of the main reasons we did it. At least creatively that was the main impetus.

Financially it was really simple. I was splitting the money with Pucci. I could work half as hard and make the same amount of money, or I could work just as hard and make twice as much money, because once you go retail the margins are just so much better.

Alan Brake: And why Tribeca? You helped create a sort of mini district down here.

David Weeks: For me it was natural, it felt the most at home. When I first moved to New York in 1990, I lived on Canal Street and I went up and down buying materials and making art and everything else. I loved the scene down there, working for Ted all those years, all those funny people that would come through, all the 1980s society artists that were part of his life. And I've always been a fan of the music that was down here.

So on a cultural level I felt a real connection with this neighbourhood. And then on a practical and economic level, Soho was of course ridiculous – the rent there was $50,000 a month, and that wasn't possible. This is a great space, and the landlord knew my work and she was very supportive.

Tribeca now, having developed, I don't know how that happened. Once one person makes a decision, other people are ready jump on it. It seemed to gel this year specifically. I think it's just the fact that we called attention to it, created the buzz that New York is so good at.

We do get a lot of foreign buyers who come in and want to see finishes and try to imagine what would look good in their homes. I think this neighbourhood is good for that, it's a place that fosters and supports that idea of international people who want to have access to what's happening in New York.

Alan Brake: It seems like your work is heading in two directions, with the lighting and then the products, the toys...

David Weeks: I studied sculpture and painting in school, and when I first started working the act of making was always the predominant element. Lighting was just an opportunity that was there at the time. I started becoming known for an aesthetic, and I met people along the way who when they first met me they would say: "I thought you'd be an older French man." Now the same people will say: "Oh, you're the lighting guy, I've heard about that lighting guy." I don't want to be the lighting guy. I appreciate it, but I wanted to be more than that.

I did some products for Kikkerland initially, smaller pieces that went under the radar, no one saw. And then the animals were the first cry for help, the first opportunity to really create an aesthetic and apply the same quality and level of detail that is in the lighting, but in a more accessible way. At the time my son was born, I was playing with action figures, and a lot of designers I think make what they need for themselves – that's the strongest type of design.

I was known to kids in school as the guy who made the Cubebot, and I was known to the older society group in New York as the guy who makes the lighting. Those things have been sort of separate for the past five or six years.

The large foam Cubebot was the moment – we brought that to Milan as our first introduction. It looked great, and it got such a great response. There was this sort of pleasure and accessibility and that's one thing I always wanted in my work. With the lighting, whether you can afford it or not, most people appreciate it for the elegance and the level of refinement, and I think the animals are the same sort of thing – it's just that accessible quality. You can see someone thinking and wrapped into the materials they're working with.

Alan Brake: Can you tell me about your plans to show a new collection later this year?

David Weeks: I haven't done a collection for a couple of years, so it's exciting to have the opportunity to have this space that we can clear out completely and do a full-blown installation of every piece and get the light the exact way we want it, and really capture the entire moment.

Carlos Salgado just came on as the design director to organise all the projects. I've been very fortunate to meet some people in Milan and companies along the way but, just because it was my own responsibility to keep track of them and keep track of the jobs, things fell by the wayside because everything else had to get done. So I'm very excited about the next year, two years, five years as we get into the rhythm of making lights, but then also making toys and furniture and carpets and whatever else comes our way.

It's funny – when we got this store some people thought it was totally nuts. And it has worked great. But I love the fact that it's working not just as a business plan. It is still based on instincts and following a grass-roots company that exists for the customers, for the collection.