Graduate shows 2015: Royal College of Art graduate Ming Kong has created a conductive material and used it to make a haptic interface for manipulating digital models and files.

For his Interfacet project, Kong developed an elastic conductive material that can be moulded into different shapes to create a tactile interface for digital modelling.

"The project attempts to revisit a fundamental design question — the relationship between form and function," said the designer, who studied on the RCA's Innovation Design Engineering course. "It explores the possibility that a new form language could be a useful technology itself."

Kong was frustrated with designing interfaces for electronics products using only flat buttons, so decided to create three-dimensional tools for navigating digital environments.

To do this, he developed a conductive silicon-based material that can sense touch and directional movement across its surface, without sensors or wires embedded within.

"I was aiming for a material that is pleasant to touch and also conductive, which enables the sensing ability," Kong told Dezeen.

Detected touch signals are transferred along a wire (not shown in these images) from a connection point in the material to a computer or a chip. They are processed by Kong's algorithm and translated into instructions for specially designed software.

To demonstrate possible applications for the material, Kong first created a set of tools that are linked to different functions within a piece of audio editing software.

"During the starting phases I just basically generated a lot of shapes through workshops and then picked the best shapes in terms of ergonomics and in terms of electrical sensitivity," he said.

Pinching, flicking and stroking the series of rubbery shapes changes elements of the digital sound file such as pitch and volume.

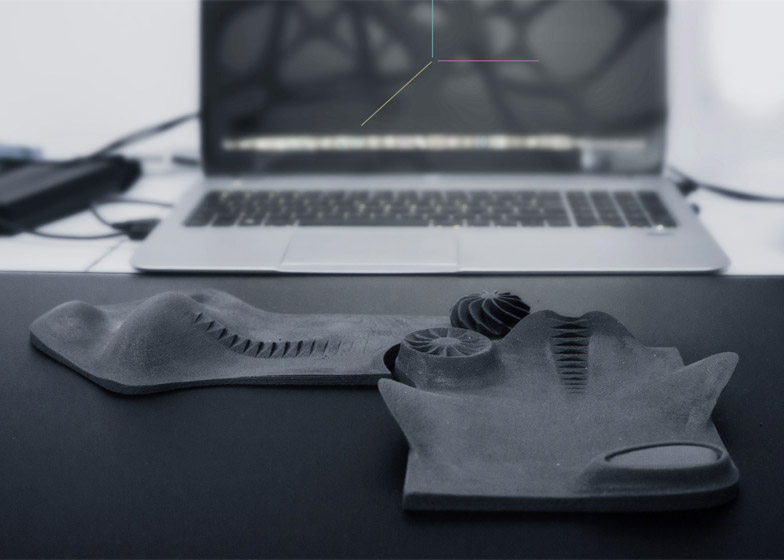

He then moved on to create a pair of sculptural trackpads, which can be used to manipulate digital models in a computer aided design (CAD) environment in response to simple hand gestures.

"You can sense where you're touching, how fast you're touching and the pressure of the touch," said Kong.

The different shapes on the pads are each used to control different motions on-screen: the right hand controls the navigation while the left is responsible for shaping.

On the right, touching rounded protrusions on each side causes the model to pan to one side or the other, while a textured channel at the top is used for moving up and down. A spiral section can be stroked for rotating.

All of the shapes on the left pad enable actions like selecting, dragging and pulling areas of the model.

Kong, who recently filed a patent for the technology, believes that it could be developed for applications such as in car interiors.

"The most interest I've had is from car interior designers and car companies," he said. "They've been interested to explore the tactile aspect of it. When you're driving you want to be able to navigate in the dash panel without being visually distracted."

"The other benefit for them would be making 3D surfaces and 3D forms interactive, and also manufacturing with a uniform material," Kong added.

Kong studied on the RCA's Innovation Design Engineering course with fellow graduate Morten Grønning Nielsen, who created a "power glove" that carves objects with its fingertips.

Both projects are on display at the institution's annual Show RCA graduate exhibition, which continues until 5 July 2015, along with a spiral staircase that wraps around the trunk of any tree.

In a similar attempt to make digital interfaces more haptic, RCA graduate Eunhee Jo revealed a prototype for a tactile fabric interface that was used to create a speaker in 2012.