Photographer Alicja Dobrucka recently stayed at and photographed Sainte Marie de La Tourette, the 1960s Dominican convent near Lyon, France, designed by Le Corbusier. We spoke to Dobrucka about her trip to the building that "looks and feels very much like a Baroque bunker" (+ slideshow + interview).

"What I wanted to capture was the austerity of the building, but also the playful organisation of space, which I found seductive," said the Polish photographer, who stayed in one of the convent's 100 cells.

"I was completely taken aback by the structure, and how random and eccentric it actually is," she added. "There were many little surprising details, like the curved rooftop of the staircase or the free-form concrete flowerpots."

Le Corbusier worked with architect and avant-garde musician Iannis Xenakis on the design of the hilltop Couvent Sainte Marie de La Tourette, which was constructed between 1956 and 1960 and which is considered a masterpiece of late Modernism.

But shortly after completion, the Dominicans decided to base most of their friars in the community, meaning that today the convent's cells are occupied by pilgrims, students and architecture devotees.

Dobrucka, who has previously worked on projects including a series of photographs of Mumbai's mushrooming skyscrapers, visited the convent with no preconceptions but was surprised by its idiosyncrasies and the way the architect handled light.

"I think there is a big gap between what Le Corbusier says and what his buildings do," she told Dezeen. "The formal inventions are extremely playful and contradict the cliché that form follows function."

Read the transcript from our interview with Dobrucka:

Marcus Fairs: Why did you choose to photograph La Tourette?

Alicja Dobrucka: Funnily enough the initial idea was to have a retreat in the monastery. I wanted to familiarise myself with Le Corbusier's language in preparation for photographing his work in Chandigarh in India that I intend to visit this summer.

Marcus Fairs: What was your impression of the place?

Alicja Dobrucka: It looks and feels very much like a baroque bunker. Le Corbusier even refer to it as an Assyrian fortress – I presume that's mainly because of the small windows. It is a huge structure with at least 100 cells, a church, a crypt, a library and meeting rooms, and a large kitchen to prepare modest meals.

The combinations of plain colours – red, green, yellow, blue and black - are the colours of floors, doors, and even pipes. It feels as if Le Corbusier made a collage of different spatial ideas as to what the structure should be and employed them all. Iannis Xenakis designed the windows that resemble musical scores. The cloister is not on the ground but on the roof, but this meditative walk is jealously reserved for the Dominicans only.

The Dominicans changed their mind once the monastery was built and decided to live among the community so at the moment there are only 10 of them residing in the building. Now the place is used for exhibitions, concerts and seminars, mixing cultural activities with religious ones. You have to be very quiet in the residential ones. The sound in the church is amazing; any whisper carries all through the space. Also the snoring of one of the pilgrims carried over to my cell.

Marcus Fairs: Describe the journey to the monastery. Is it easy to get to?

Alicja Dobrucka: There are few ways to reach the monastery. You can fly to Lyon and take a bus or drive. I booked a cell in the monastery itself.

I arrived late, after the reception hours. There was a letter pinned to the door with my name on it. It stated the location and the number of my cell as well as the code for the front door. After a quick glimpse at the letter I opened the door and was grabbed by a Dominican asking whether I was the late guest. He lead me to the dining room.

There were four large square tables around which were sitting the priests, the retreat guests as well as some students who came to prepare for their Baccalauréat. The meal was simple, something that looked like huge meatballs with rice and salad. Red table wine was also served. Unlike the guests, the fathers and brothers did not drink much of it.

The design and proportion of each cell is the same as the small hotel rooms at La Cité Radieuse in Marseille. The cell I stayed in was surprisingly comfortable. It was long and narrow, with a green floor and white walls made of thick rendering that recalled the interior of a grotto. On the door of my room were pinned the house rules: do not invite anyone in your cell, do not bring food or drinks, and do not have conversations in the corridors.

There was a sink on the left hand side just by the entrance and a set of shelves and wardrobe, behind which there was a single bed. A table was by the window and the room ended with a little balcony. There was a long rectangular aperture the length of the door that you could close with a wooden shutter. When it was open, you could see into the corridor and people walking by could catch a glimpse of the side of the room.

Marcus Fairs: What was it like to photograph?

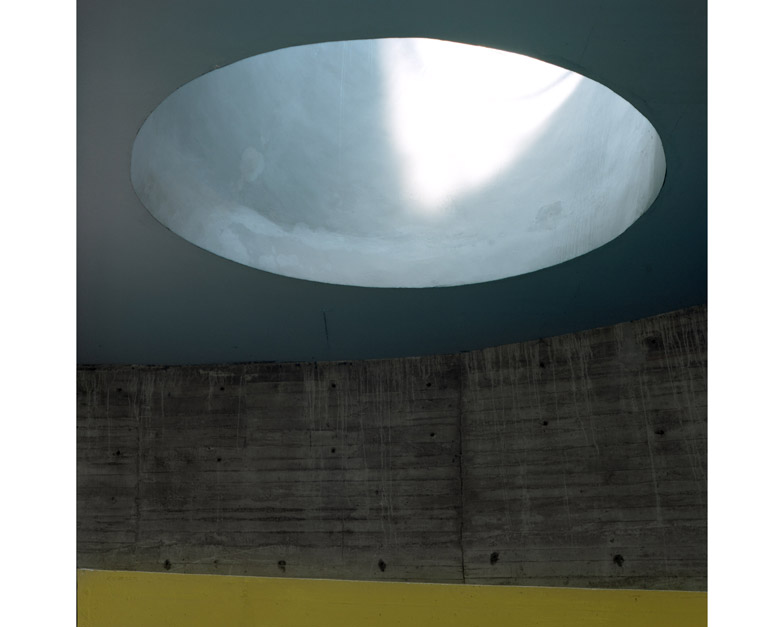

Alicja Dobrucka: I was completely taken aback by the structure, and how random and eccentric it actually is. Certain elements of the building I kept coming back to – like what Le Corbusier called the light guns, that allow the light to access the church. The intensity and direction of light would change the perception of the volumes in the church. Somehow photographing the building allowed me to understand it.

Brother Marc Chauveau, who has curated an exhibitions of the monochrome painter Alan Charlton and who is preparing another with Anish Kapoor, commented upon how the building had been represented through photography: if the early photographers strived to present a general view, later photographers focus on the details of the architecture and how it is transformed by light and shadow.

Marcus Fairs: Was it what you expected?

Alicja Dobrucka: I came there with no expectations. I just wanted to feel the structure and hence decided to stay in it. The building kept on changing depending on the light. I thought that the outside of the building came to life in the evening and the inside of the building came to life during the day.

I really loved the big and blank concrete walls and they were essential for me to be in the series. I think that what I wanted to capture was the austerity of the building, but also the playful organisation of space, which I found seductive. There were many little surprising details, like the curved rooftop of the staircase or the free-form concrete flowerpots.

Marcus Fairs: Was this a commission or a self-initiated project?

Alicja Dobrucka: It was a self-initiated project. I may actually go back one day to photograph the other parts of the building that are not accessible to visitors, like the rooftop cloisters. It is still very much a work in progress and it may well become a part of a much bigger series, which could be combined with other pictures I will have taken of other Le Corbusier's buildings.

Marcus Fairs: Have you photographed any of his other buildings?

Alicja Dobrucka: This was the first time I have visited any of his structures. On this trip I also visited the small house he built for his parents in Corseaux next to Lake Léman, where he also included a room with separate access for himself and his wife, with bunk beds.

Why have single beds, just like in a monastery? Is this linked to a puritan work ethic? This single-bed obsession is continued in his cabanon at Cap Martin as well as in the camping huts that he designed there.

Marcus Fairs: What are his buildings like to photograph compared to those of other architects?

Alicja Dobrucka: I think there is a big gap between what Le Corbusier says and what his buildings do. The formal inventions are extremely playful and contradict the cliché that form follows function.

Marcus Fairs: What is your approach to architectural photography?

Alicja Dobrucka: To avoid doing architectural photography!