Postmodernism is back: introducing Dezeen's Pomo summer

Pomo summer: this summer, we celebrate the revival of the architecture and design movement everybody loves to hate. To kick off the series, Dezeen editor Anna Winston explains why Postmodernism is back.

Love it or hate it, Postmodernism is back in vogue. Welcome to the first in a summer-long series in which Dezeen explores the movement, its legacy and its return.

Over the next few weeks, we'll be interviewing some of Postmodernism's leading architects and designers, profiling key buildings and products, as well as highlighting a new wave of Postmodern design.

This week, we'll publish the Dezeen guide to Postmodernism, written by Glenn Adamson, director of New York's Museum of Arts and Design (MAD).

Later in the season, we'll round up some of the best examples of work from the Postmodern revival, while regular Dezeen columnist Sam Jacob – a co-founder of the now defunct Radical Postmodernist architecture studio FAT – to examine the movement's ongoing relevance.

In his debut column for Dezeen, US critic and educator Aaron Betsky will examine how the experimental approach of the Postmodernists has shaped architectural education, influencing new generations of students.

And Charles Holland – a co-founder of FAT and now director of London studio Ordinary Architecture – will also share his top 10 lost Postmodern classics.

Postmodernism began in the late 1970s as an ideological reaction against the utopian ideals of Modernism. While the latter was concerned with purity of design, less being more and proscriptive ideas about taste and order, Postmodernism was about ornamentation, contradiction and experimentation.

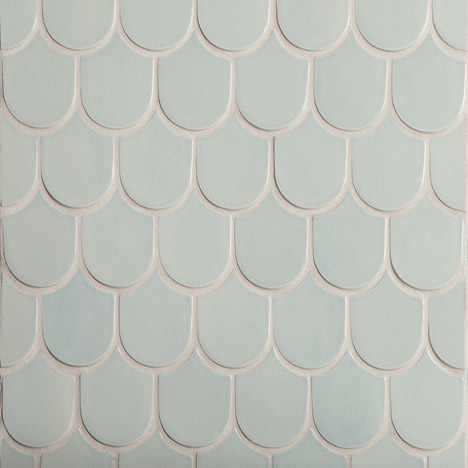

Aesthetically this manifested itself in bright colours, bold forms constructed from simplistic shapes like a child's building set, and decorative flourishes that had nothing to do with function.

It reached fever pitch in design in the 1980s, and continued in architecture right through to the late 1990s.

Despite its pervasive reach, Postmodernism was the design movement hardly anyone wanted to be part of. Glenn Adamson, one of the co-curators of the V&A's major Postmodernism exhibition in London in 2011, found it almost impossible to track down architects who would admit to being Postmodernist.

"It got to the point that we would tease them: 'are you now or have you ever been a Postmodernist?'" he says.

Critic Stephen Bayley described the V&A's Postmodernism exhibition as "a chamber of horrors", but it proved a remarkably prescient retrospective. Since the exhibition finished, young designers from Milan to New York have been slowly but surely reviving the Postmodern aesthetic.

It started with a wave of renewed interest in the work of the Memphis Group – a hugely influential cadre of designers led by Ettore Sottsass that began as a marketing exercise and went on to help define the style of an entire decade in the 1980s.

Dezeen wrote about the revival last year, after Milan design week was flooded with Memphis-inspired pieces.

Small firms like Eindhoven studio OS & OOS have been among the aesthetic torch-bearers for the Postmodern revival, although bigger brands like Hay have also climbed on board.

In London, design store Darkroom has featured increasingly Postmodern-influenced collections by a range of small studios. And in Milan this year, furniture brand Kartell released a collection of nine original pieces by Ettore Sottsass, which it has put into production for the first time, while Konstantin Grcic debuted his cartoonish Sam Son chair, which has a back support shaped like a pool noodle.

Architecture, as always, is a bit slower on the uptake – it takes five years to complete a building and five months (if that) to realise a furniture concept. But MVRDV's headline-making Markthal in Rotterdam – with its chunky tunnel-like arch and oversized bright fruit murals, could easily be viewed through a Postmodernist lens.

The latest version of Postmodernism is a bit more toned down than the original – softer around the edges, less obviously like children's building blocks, but perhaps more infantile in its superficiality and brazen commercialism.

Earlier this year, one of the Postmodernism's early champions, Alessandro Mendini, told Dezeen that there is no more ideology in design. Certainly, the Postmodern revival is more interested in looks than in grand ideas. But whether he was right or wrong, the echoes of Postmodernism are clearly visible.

It helped break down the boundaries between styles and disciplines, encouraging and allowing designers to be experimental in making new shapes and bringing in references from the past as well as exploring the possibilities of technology.

In architecture, designers like Robert AM Stern and Michael Graves looked to the past, championing a return to decoration and incorporating columns and pediments into their facades. In furniture and product design, the focus was often on developing new shapes and challenging ideas about how everyday objects should look and function.

While the furniture is starting to attract high prices at auction, many of the best historic examples of Postmodern architecture are now under threat. Graves' Portland Building was saved from demolition last year, following one of the first preservation campaigns for a Postmodern building. Dezeen columnist Alexandra Lange, although not among the fans of the building, was among those convinced it was worth saving.

But if Postmodernism was ultimately about freedom to experiment, about humour and levity after years of serious-minded Modernism, you could argue that it never really went away. It's just been lingering in the background, waiting until we became so utterly bored of tastefulness that it could find a way to elbow itself back into our collective consciousness, in a more image-led and superficial way than its originators could ever have dreamt up.

After years of tasteful Modernist revivals, of mid-century everything, of blonde-wood furniture and muted upholstery palettes, of po-faced brickwork used to disguise developer-friendly housing, of artfully styled succulents against a backdrop of Scandinavian repro-classics, it's time for something a bit more fun.

Illustration is by Daniel Frost.