Graduate shows 2015: traditional machiya houses in the Japanese city of Kyoto are under threat from modern development, so Royal College of Art graduate Adam Roberts proposes stacking them up to make them more cost and space efficient (+ slideshow).

Roberts visited Kyoto on an exchange programme during the final year of his architecture studies at the RCA and learned about the plight of the machiya houses – traditional townhouses with a shop space opening onto the street at the front and living spaces behind and on the floors above.

The buildings proliferate in Kyoto's historic centre but, after centuries of being erected by skilled carpenters using traditional techniques, they are considered economically unsustainable by developers and are regularly removed and replaced with car parks and apartment blocks.

In addition, families who have occupied these buildings for generations are demolishing them and constructing more modern homes rather than conducting expensive repairs – with the few exceptions including one renovated in 2012 by Q-Architecture Laboratory.

"Machiya urbanism, which contributes so strongly to people's experience of Kyoto, is gradually in decline as the technology of machiya has not advanced over the past 100 years to accommodate societal shifts," Roberts told Dezeen.

"The long-established traditions of machiya urbanism are at risk of being absorbed by modernity and globalisation if the machiya typology cannot adapt to the challenges of future years," Roberts said.

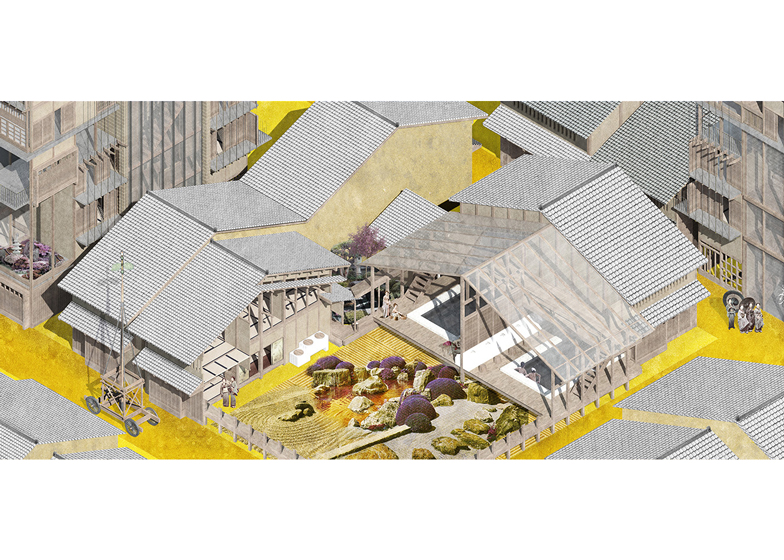

For his project, entitled Kyomachiya Futures, Roberts proposes updating the typology in response to increasing land pressures by stacking residences into vertical towers, making more efficient use of the available space.

The towers would reach to the city's maximum permitted height of 35 metres and would accommodate an equivalent number of people to the low-quality mansion blocks that are currently redefining the Kyoto skyline.

"The machiya tower takes the linear principles of the traditional machiya and verticalises them using a system of split levels and stacked apartments," Roberts explained.

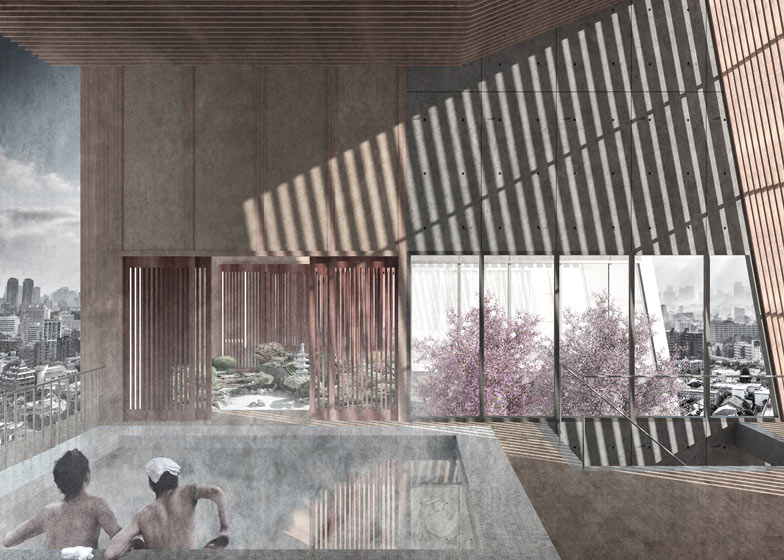

Lower storeys would contain living quarters designed traditionally around the dimensions of tatami floor mats. These spaces would feature sliding walls, enabling their occupants to adapt them to their individual needs.

Commercial spaces such as restaurants, onsen baths or ryokan inns would be located near the top to help the buildings generate income over successive generations.

Instead of the time-consuming and complex carpentry processes traditionally used to build machiya, Roberts believes that modern CNC-cutting technologies could enable speedier construction while retaining the traditional feel of these structures.

"I propose that with the development of automated timber pre-cut technologies, in which Japan is an industry leader, machiya can achieve comparable heights and densities while retaining traditional Japanese values," he said.

Aesthetic elements that identify a building as a machiya – such as repeating bay windows, typically covered with lattices that vary in density to identify the type of shop – would be applied to the towers to provide a connection with the area's architectural heritage.

"Through the transposition of their architectural fundamentals to a modern, densified form, the project envisages the cultural reprogramming of the residence to reflect evolving values of Japanese home life," Roberts added.

Another conceptual skyscraper with human statues supporting its floors was also presented at this year's RCA graduate show, alongside a proposal for a dystopian tax haven.

Roberts developed the project as part of the ADS3 unit at the RCA, tutored by architects Torange Khonsari, Andreas Lang and Francesco Sebregondi. Students were asked to explore ways in which architects can intervene in the field of politics.

Other projects from this unit included a a high-rise theme park where the rides are replaced with hazardous scenarios.