The architecture and design of the counterculture era has been overlooked, according to the curator of an upcoming exhibition dedicated to "Hippie Modernism" (+ slideshow).

The radical output of the 1960s and 1970s has had a profound influence of contemporary life but has been "largely ignored in official histories of art, architecture and design," said Andrew Blauvelt, curator of the exhibition that opens at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis this autumn.

"It's difficult to identify another period of history that has exerted more influence on contemporary culture and politics," he said.

"Much of what was produced in the creation of various countercultures did not conform to the traditional definitions of art, and thus it has largely been ignored in official histories of art, architecture, and design," he said. "This exhibition and book seeks to redress this oversight."

While not representative of a formal movement, the works in Hippie Modernism challenged the establishment and high Modernism, which had become fully assimilated as a corporate style, both in Europe and North America by the 1960s.

The exhibition, entitled Hippie Modernism: The Struggle for Utopia will centre on three themes taken from taken from American psychologist and psychedelic drug advocate Timothy Leary's era-defining mantra: Turn on, tune in, drop out.

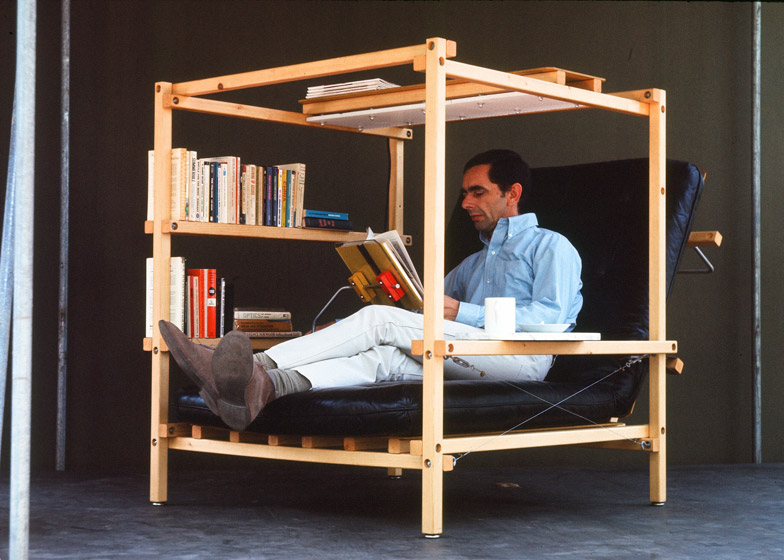

Organised with the participation of the Berkeley Art Museum/Pacific Film Archive, it will cover a diverse range of cultural objects including films, music posters, furniture, installations, conceptual architectural projects and environments.

The Turn On section of the show will focus on altered perception and expanded individual awareness. It will include conceptual works by British avant-garde architectural group Archigram, American architecture collective Ant Farm, and a predecessor to the music video by American artist Bruce Conner – known for pioneering works in assemblage and video art.

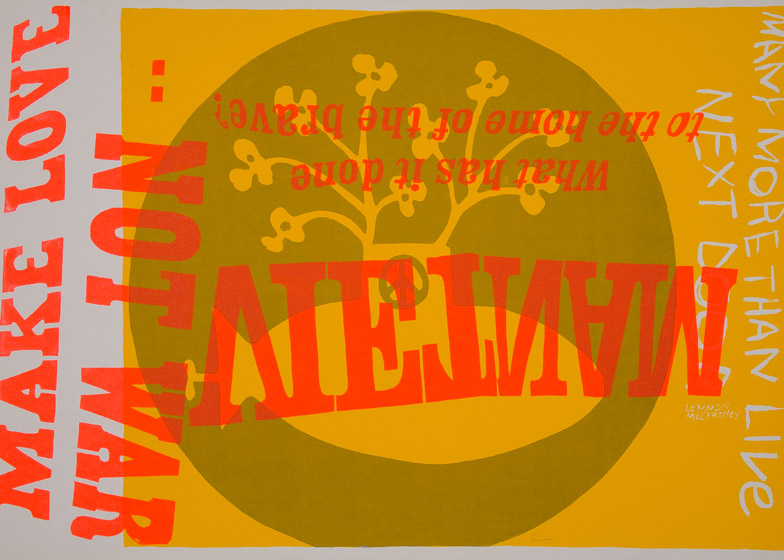

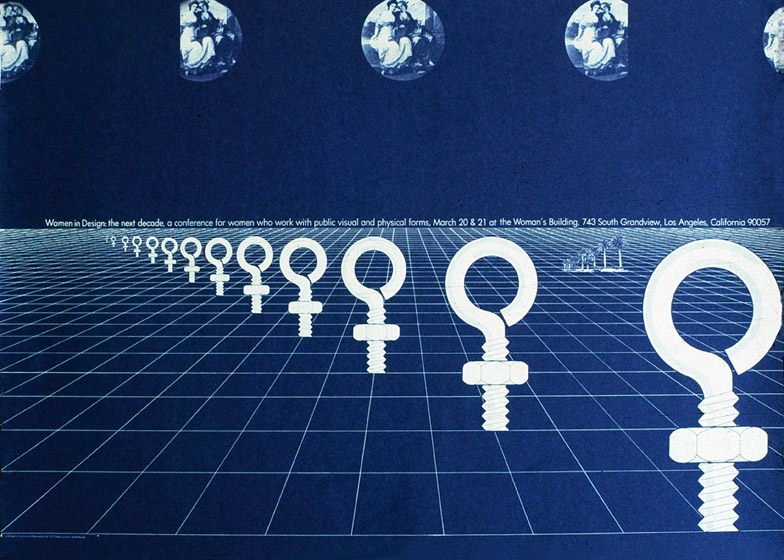

Tune In will look at media as a device for raising collective consciousness and social awareness around issues of the time, many of which resonate today, like the powerful graphics of the US-based black nationalist party Black Panther Movement.

Drop Out includes alternative structures that allowed or proposed ways for individuals and groups to challenge norms or remove themselves from conventional society, with works like the Drop City collective's recreation dome – a hippie version of a Buckminster Fuller dome – and Newton and Helen Mayer Harrison's Portable Orchard, a commentary on the loss of agricultural lands to the spread of suburban sprawl.

The issues raised by the projects in Hippie Modernism – racial justice, women's and LGBT rights, environmentalism, and localism among many other – continue to shape culture and politics today.

Blauvelt sees the period's ongoing impact in current practices of public-interest design and social-impact design, where the authorship of the building or object is less important than the need that it serves.

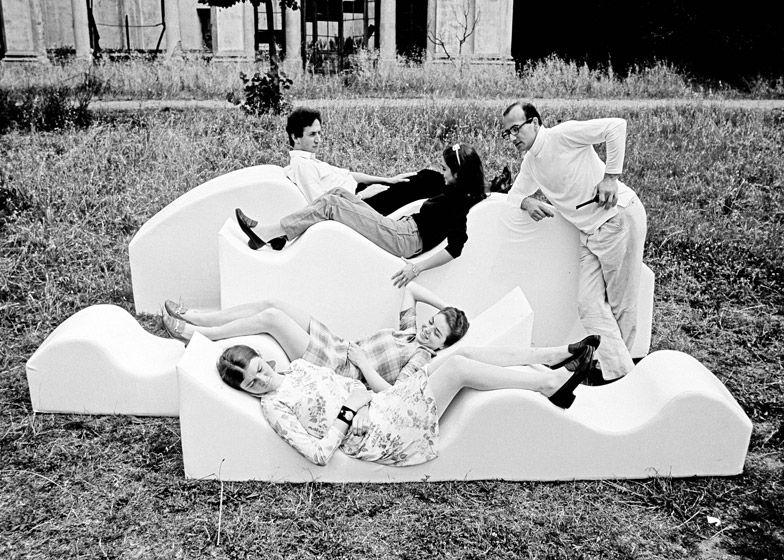

Many of the exhibited artists, designers, and architects created immersive environments that challenged notions of domesticity, inside/outside, and traditional limitations on the body, like the Italian avant-garde design group Superstudio's Superonda: conceptual furniture which together creates an architectural landscape that suggests new ways of living and socialising.

Blauvelt sees the period's utopian project ending with the OPEC oil crisis of the mid 1970s, which helped initiate the more conservative consumer culture of the late 1970s and 1980s.

Organised in collaboration with the Berkeley Art Museum and the Pacific Film Archive, Hippie Modernism will run from 24 October 2015 to 28 February 2016 at the Walker Art Center.