Photo essay: Canadian photographer NK Guy first went to Burning Man festival in 1998, and has returned to the Nevada desert each year since to shoot the artworks that spring up then vanish just as quickly (+ slideshow).

NK Guy's photos document the creation of the vast 68,000-strong "city" that pops up at the end of each summer in the Black Rock Desert, and disappears just over a week later.

Giant figures, sprawling temples and fantastical vehicles are among the temporary artworks that have provided the London-based photographer with just as much visual material as the monumental clean-up effort after the installations are burned and the festival finishes.

He describes the stories behind some of his favourite images in this essay written for Dezeen, which coincides with this year's Burning Man event and the launch of the book of his photographs published by Taschen.

Once a year, from the barren clay of the Nevada desert rises a temporary city. Many people think of Burning Man as a festival, which isn't entirely unreasonable. But "festival" is a term preloaded with a lot of assumptions. People think of music festivals, of big parties, of naked hippies on drugs.

Burning Man certainly has that component, but what makes it interesting to me is how it transcends mere party to become a social experiment and incubator of truly remarkable art.

It starts with the desert. Black Rock City is a temporary city of 68,000 constructed on a playa, or flat dry lake bed, in northern Nevada. Despite the city's size, it is dwarfed by the barren and almost Martian landscape of Nevada's Great Basin. The perfectly flat plain, ringed by mountains, forms a surreal setting for the event.

The circle and pentagon inscribed on the land reflect the remarkable level of organisation and structure that characterises the event. This is no chaotic field of festival tents, but a structured and zoned temporary city. The radial roads are labelled by the hour of the clock, and the concentric rings are given alphabetically arranged names. This allows for an unambiguous coordinate system for emergency services.

The inner streets are zoned for participatory interactive camps, with private camps zoned further out. The Burning Man figure himself stands at the very centre of the city plan; the gnomon of the sundial and the axis mundi, where the earth and the heavens meet. The central circle is left open to house massive art installations. This experiment in urban planning was devised between 1997 and 1999 by Rod Garrett.

The physical design of the Center Camp Cafe is another of Garrett's legacies (he died in 2011). The cafe is used as a performance space for music and spoken word, as a meeting place and social hub, an art gallery for smaller works, and also a supplier of coffee. The structure has very specific requirements. It must act as a shade shelter for hundreds of participants, must be storable in Burning Man's fleet of offsite containers and redeployed quickly each year, and must be able to withstand gale force winds.

Garrett opted for a design based around a tensile toroid: a ring of steel cables and wooden posts, supporting a canopy of open-weave nylon that covers some 45,000 square feet or 4,200 square meters. Sloping sides help direct the blowing wind up and over a central oculus that was criss-crossed by cables. A tall crown of flags, illuminated by night, serves as a constant navigational landmark to participants. Outside the ring stand row upon row of bike racks – Black Rock is very much a bicycle city.

One of the most successful long term conceptual projects at Burning Man is the annual temple, an architectural tradition that will probably come as a surprise to many.

Ever since 2001 there has been a vast wooden temple located far out in the open desert. David Best's 2000 Temple of the Mind was technically the first, but it was quite small and not located on the 12 o'clock axis. David pioneered the concept and has designed many, but various other artists and teams have been responsible for many others.

These temples aren't centres of carnival celebration or sites for religious dogma and ritual. Instead they're built to focus on the universal human experience of grief and loss. They're community structures, which Burning Man participants adorn with messages, mementos and other personal testaments of loss throughout the week. Then, when the building is finally burned at the end of the event, the contributions are released skyward.

In 2002, the Temple of Joy by David Best and the Temple Crew comprised dimensional lumber on conventional North American platform framing, as used for residential homes. However, the intricate detail arose from factory waste – sheets of thin Baltic plywood left over from the manufacture of children's toy dinosaur models. This material, obsessively applied across every surface, gave a complex layered texture that harkened back to an architectural language that predates the modern obsession with sterile purity of line and form.

The temple felt almost organic, the mud-coloured wood seemingly thrust out of the desert surface itself.

Another of radically different design was 2011's Temple of Transition by the International Arts Megacrew. This massive structure was believed to be the largest freestanding wood building, built without a foundation, ever constructed.

Its central tower was 120 feet, or 36 metres, in height. It was built using dimensional lumber for framing with plywood sides. The platform at the front was used to transform the building into the world's largest musical instrument.

The Temple of Whollyness by Gregg Fleishman, Lightning Clearwater III, and Melissa Barron was 2013's Temple, built around a very different construction principle than its predecessors.

Instead of conventional framing, a geometric pyramid was built using wooden joiners, or nodes, that Gregg developed in the 1980s. The structure was entirely made of wood – no support cables or metal fasteners were used. This had the added bonus that there was little unburned metal to rake up when the building was burned.

Other installations feel like a movie set in terms of scale, detail, and ambition. One example is Pier 2 by Kevan Christiaens, Matt Schultz and the Pier Group of volunteers, which featured La Llorona, a replica sunken galleon, at its far end.

The ship could be boarded, and was full of distressed set pieces – skeletons, cannons, ship logs. The landboard dinghy is filled with participants, rowing nowhere.

Some works are built on a more personal or human scale. Gearhead, by Steve Hall and Becky Stillwell was a wooden sculpture, containing a complex arrangement of gears, levers, and spinning heads, and operated by a hand crank. When lit by black light at night it glowed intensely.

Black Rock is a city where most motorised vehicles are banned, and those permitted have to be rolling art vehicles restricted to five miles per hour mph.

The CS (Clock Ship) Tere by Andy Tibbetts was a handcrafted pirate ship vehicle, driven by an ingenious front wheel with no axle. The propane flame effects produced "sheets" of fire, as a naval pun.

Other rolling vehicles included the ever-popular scrapyard masterpiece, El Pulpo Mecanico by Duane Flatmo and Jerry Kunkel. The animated octopus was built from scrap steel, and its chariot covered with bits of old aluminium. It could wave its mechanical tentacles, to the obvious joy of participants.

There were also the Cupcake Cars by Lisa Pongrace, Greg Solberg, and the Acme Muffineering team, photographed in 2006. The rolling cupcakes and muffins are powered by electric motors, use solar-charged batteries, and can hit up to 18 miles per hour. Each car is unique, and made as a personal project by its owner, in collaboration with fellow muffineers.

The tough conditions of the Black Rock Desert form an incredible learning environment for artists and designers, and this has been used to great advantage by a team from the University of Westminster's School of Architecture and the Built Environment, London. For the past three years Arthur Mamou-Mani and Toby Burgess have been leading architectural design courses which culminate in the creation of installations for Black Rock. Students are encouraged to fundraise and apply for art grants from the Burning Man organisation, in order to construct the actual works on-site.

Much architectural education focuses on theory and studio work, but here the students are forced to learn how to transform their lovingly detailed CGI and model renderings into an actual physical artefact that can cope with the harsh unforgiving environment of a windswept desert.

The Man, by Larry Harvey, Jerry James, Dan Miller, and the ManKrew, is the centrepiece of the whole event. Constructed from wood, with a head like a Japanese lantern, the basic skeletal design remained unchanged from the mid 90s through to 2013.

Immense pyrotechnics mark the end of the Man. In 2011 the Man was depicted as marching between two peaks, symbolising transition and change.

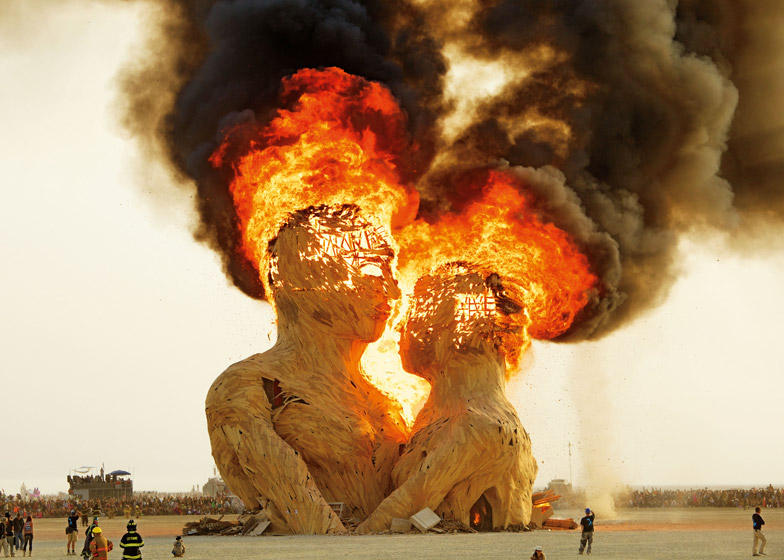

Other memorable large-scale installations include Embrace, by Kevan Christiaens, Kelsey Owens, Bill Tubman, Joe Olivier, Matt Schultz and the Pier Group, from 2014.

The massive heads and torsos, dubbed Alpha and Omega rather than anything gender-specific, were 70 feet or 21 metres at their tallest. Unusually, they were burned in a daytime ceremony rather than at night.

The year before, a flying saucer was set alight. The base, designed by Lewis Zaumeyer and Andrew Johnstone, was intended to reflect the year's art theme: Cargo Cult, after the spontaneous syncretic religions that sprang up on some South Pacific islands following contact with the West over several centuries; most prominently after World War II.

The islanders, it is said, would build wood planes and sand runways in the hope of summoning the return of cargo. Burning Man founder Larry Harvey felt that the tale was suitable for our own technological civilisation - a totemic manifestation of our rapaciously inexhaustible desire to obtain a supply of technological cargo from external, perhaps alien, visitors.

Then there's always cleanup. Burning Man has a policy of "leave no trace", and requires all participants to clean up after themselves. Following the event, teams of workers scour the desert floor, looking for any leftover rubbish.