Pomo summer: Hans Hollein conceived the Vulcania Centre Européen du Volcanisme amusement park – one of the latest examples of Postmodern architecture in our series – as a journey to the centre of the earth, citing Dante's Inferno among his influences for the subterranean design (+ slideshow).

The partially submerged geological park in France's volcanic Auvergne region is rich in the witticisms that characterised Hollein's work, featuring a miniature artificial volcano, water-spewing crater and an underground vibrating cinema.

While Hollein followed up his training at Vienna's Academy of Fine Arts in 1956 under the tutelage of notable Modernists Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Frank Lloyd Wright and Richard Neutra in America, he went on to become one of the pioneers of the Postmodern movement.

His move away from Modernism began in 1963, when – a year prior to setting up his own studio in Vienna – Hollein issued a manifesto-like statement renouncing the movement's infamous motto "form follows function" in favour of a more experimental type of architecture.

"Form does not follow function," he asserted. "Form doesn't originate by itself. It is the great decision of man to make a building into a cube, a pyramid or a sphere."

A decade later, architecture critic Charles Jencks identified Hollein as a trailblazer of the new Postmodern movement, among a line-up of architects including Robert Venturi, Charles Moore and Aldo Rossi.

As Hollein's career progressed, Postmodernism began to fall out of fashion. But he continued to explore its aesthetic with his own agenda.

Work began on Vulcania towards the tail end of the movement in 1994, and completed in 2002 long after Postmodernism's heyday had passed. Nevertheless, the project is a development of the striking visual vocabulary that Hollein and his contemporaries had adopted.

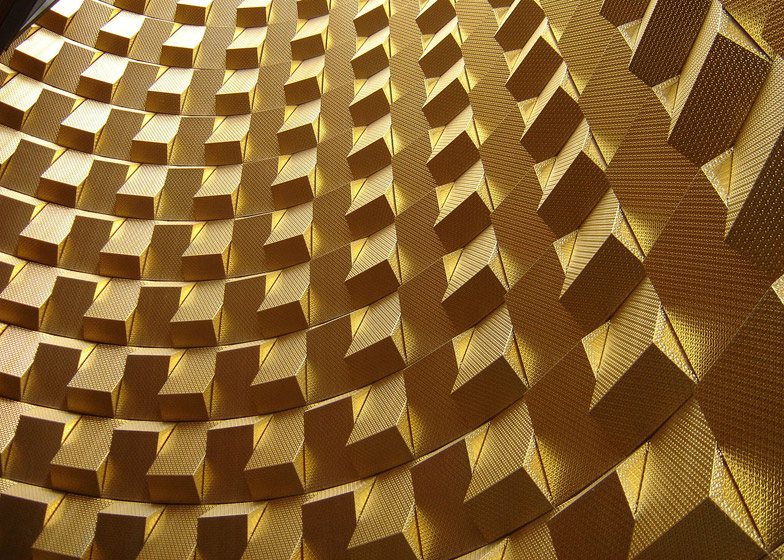

At the heart of the complex is the bold form of a volcano, simplified to a geometric cone. Clad in slabs of solidified lava, its curving form is split to reveal a fiery gold interior and underground levels hosting eruption simulators, a rollercoaster and galleries.

The fissure that splits the cone in two is a recurring theme in Hollein's work. He often disrupted the facades of his buildings with purposeful flaws – most notable in a gold-lined crack that appears in the face of Jewellery Store Schullin I in Vienna.

"His idea of the crack impressed me and led me to the ideas of fragmentation, explosion, etc," said architect Zaha Hadid. "A true innovator of the discipline in a time when architecture had to radically reinvent itself."

Around 60 per cent of the 12,500-square-metre complex is situated below ground in a crevice created by an old lava flow, with only the artificial volcano and a geyser-shaped fountain visible above the surface.

This subterranean design had its roots in his underground designs for a pair of German museums – the Mönchengladbach Museum (1982) and his unrealised plans for a Guggenheim Museum in Salzburg (1989) – as well as science-fiction novel Journey to the Center of the Earth by Jules Verne and etchings of Dante's Inferno.

"I had the idea to use the theme descent to the centre of the world so I put more than half the programme into an old lava stream," he told architecture critic Justin McGuirk in an interview two years after the park's opening.

Hollein first began practising his Postmodern approach with a cluster of small but influential projects. His first, the 14.8-square-metre Retti candle shop in Vienna, featured an aluminium frontage and phallic doorway and landed him an architecture prize worth more than the budget for the entire store. This was quickly followed by his first American project – the Richard Feigen Gallery in New York, which completed in 1969. Similar commissions quickly followed.

The Museum Abteiberg, one of his best-known major public commissions, marked a shift change in the scale of his work. Hollein was given architecture's most prestigious award, the Pritzker Prize, two years later.

"Hans Hollein seems to be that rare thing – an architect to whom Postmodernism in every sense comes utterly naturally," said architecture critics Kester Rattenbury, Robert Bevan and Dezeen columnist Kieran Long in their 2004 publication Architects Today.

"His full, exploratory Postmodern range – 'Everything is architecture,' he says – is best understood on his home ground."

The controversial Haas House in Vienna with its futuristic mirrored facade, and the Museum für Moderne Kunst in Frankfurt, known as the "slice of cake" thanks to its triangular shape, were among his later important buildings.

Historically referential and often comical elements cropped up throughout Hollein's oeuvre – in a coffee service shaped like miniature aircraft for Italian manufacturer Alessi and again in Vulcania where its 28-metre-tall artificial volcano appears farcical in the shadow of its gargantuan, natural neighbours.

These humorous touches were not overlooked by the Pritzker jury when Hollein became the first and only Austrian architect to win the award in 1985.

They described him as "a master of his profession – one who with wit and eclectic gusto draws upon the traditions of the New World as readily as upon those of the Old."

Adam Nathaniel Furman, who runs The Triumph of Postmodernism blog, commented on the synthesis of historical and futuristic references that is often present in Hollein's work: "His compositions never glibly reproduced features directly plucked from previous periods with a cynically knowing wink, but were rather exotic new dishes cooked from ingredients that the observer can taste, smell and somehow recognise individually," Furman told Dezeen.

"His buildings fuse a delight in the sensuality of buildings, pleasure in the allusive power of historic form, with the hypnotic thrill of a small dose of psychedelic futurism – all qualities that come to the fore in his Vulcania project with its otherworldly, inverted, gold crystalline cone, that speaks at the same time of geology, of space ships and rockets, of the pyramids, and of a place for psychedelic experiences. A typically Hollein mix of associations."

Vulcania's progress was fraught with controversy, not for its futuristic form as was the case with the design of Haas House, but for the patronage of the former French President Valéry Giscard d'Estaing.

Throughout its construction, the park was scathingly referred to as the Giscardoscope and in the lead up to its opening media reports heralded it as the latest in a succession of thinly veiled vanity projects by French presidents – following Charles de Gaulle's airport, Georges Pompidou's art centre and François Mitterrand's Louvre.

Conservationists too were concerned about the project and its potentially detrimental impact on the region. Green Party member Daniele Auroi claimed the park would become a "Disneyland in nature" rather than fulfilling any scientific mission.

"It'll be Giscard's monument to himself," she said.

But despite attempts to derail the project, the park opened to the public in 2002, almost a decade after work started.

A bookend to the Postmodern movement, there was an outpour of sentiment towards the project and its iconic volcano centrepiece when Hollein died at the age of 80 in 2014.

Considered a prime example of his museum design, plans for the project were included in Hollein's retrospective at the MAK gallery in Vienna. Opening just months after after his death, the show spotlighted the influence of the architect's work and his importance within Postmodernism.