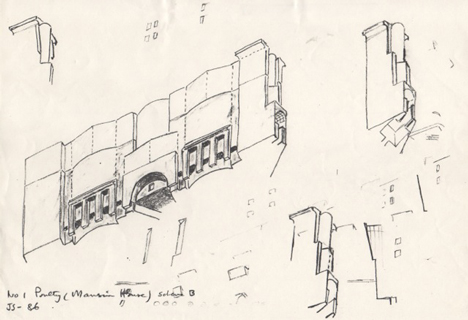

Postmodern architecture: No 1 Poultry, London, by James Stirling

Pomo summer: the last project in our Postmodernism season is by one of Britain's greatest architects. With its distinctive stripy facade, rounded clock tower and colourful courtyard, No 1 Poultry was James Stirling's last completed building, but is currently the focus of a preservations battle involving some of the world's best-known architects (+ slideshow).

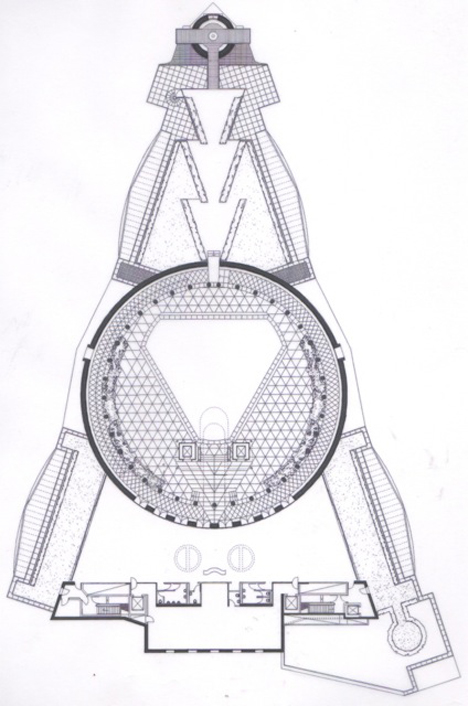

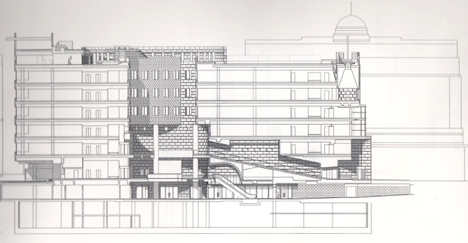

Built on a wedge-shaped site in the heart of the City of London, No 1 Poultry contains shops at ground and basement levels, with five floors of offices, and a roof garden and restaurant above. The building's ship-like prow and clock tower with projecting balconies dominate the junction at Bank Underground Station. Its exterior is clad in stripes of pink and yellow limestone, and its two long facades are characterised by the layering of angular and curved forms.

Designed by Stirling in 1985 but not completed until 1997 – five years after his death – No 1 Poultry was one of the British architect's last projects. He was knighted in recognition of his contribution to architecture just days before his death and in 1996, the RIBA even renamed their prestigious Building of the Year Award the Stirling Prize after him.

Born in Glasgow in 1926, Stirling studied architecture at the University of Liverpool, and later became as assistant at the firm of Lyons, Israel and Ellis. Over the 1950s and 1960s, a new generation of influential British architects would pass through the London-based firm before going on to become well known in their own right, including Neave Brown, Richard MacCormac and Rick Mather, as well as James Gowan, Stirling's future business partner. The duo founded Stirling and Gowan in 1956, and quickly gained national recognition.

Gowan was often overshadowed by Stirling's sometimes outrageous behaviour and public persona. The duo split after the completion of their Engineering Building at the University of Leicester in 1963 – commonly considered the UK's first Postmodern building – and Stirling continued with new partner Michael Wilford.

Despite being some of the most critically acclaimed Modern structures in the UK within architecture circles, Stirling's buildings were plagued with problems and were often less appreciated by the British establishment and wider public.

Stirling and Gowan's history faculty and library at Cambridge University leaked and featured wildly varying internal temperatures.

"As well as being an original and internationally admired talent, who is sometimes said to be the Francis Bacon of British architecture, he also designed some of the most notoriously malfunctioning buildings of modern times," wrote Guardian architecture critic Rowan Moore in 2011.

"Stirling was seen as the very type of the award-winning architect whose buildings don't work. He was, to boot, arrogant, lecherous and sometimes boorish. At a party in the apartment of the New York architect Paul Rudolph, he chose to express himself by urinating against its huge window, from the terrace outside, facing into the crowd of guests."

Some time in the early 1970s, Stirling's architectural style seemed to shift. "Seemingly overnight Stirling became Postmodernism's unsuspecting and unwitting poster child," wrote critic Martin Filler. According to Andrew Saint: "his architecture stopped being clipped and wiry and grew monumental and fat."

Architect and theorist Charles Jencks, in his seminal book The Language of Postmodern Architecture, drafted Stirling into the Postmodern cause, earmarking him as part of the revolt against the "high tech" Modern architecture of his contemporaries.

Stirling rejected the Postmodern label. But he did acknowledge that the style he was developing was in direct opposition to the "grey" architectural mainstream.

"If we do another building in this country, it should be colourless, perhaps grey or brown – preferably the latter – or better still maybe just invisible," he joked in a speech at the Clore Gallery in 1987.

In this period, humour and surprise became Stirling's architectural language. Many of the design elements of No 1 Poultry seem to be intended to suggest a child's toy: the cylindrical courtyard, with its triangular lightwell and coloured walls; the submarine-like clock tower; and the striped facades.

Like many of the best Postmodern buildings, No 1 Poultry also makes some provocative historical quotations and references to its historic neighbours.

"The building makes people smile, it's the slightly naughty child but very much part of the family of historic listed building around Bank Junction – it has the same DNA as Hawksmoor's Saint Mary Woolnoth, Lutyens Midland Bank and Soane's Bank of England," Laurence Bain, project architect and former partner at James Stirling Michael Wilford and Partners, told Dezeen.

The building's height, symmetrical plan and divided facade matches the surrounding buildings. Stirling planned it around a longitudinal axis with two similar facades. These are divided horizontally in three and vertically into five, with the layers alternating between angled and curved forms. Both facades have a central wedge-shaped entrance that gives access to the central rotunda, with two arcades on either side.

No 1 Poultry's clock tower, with its horn-like projecting balconies, also mimics nearby structures, as well as referencing Greek and Roman rostral columns, which were erected to celebrate naval victories.

"Amongst its sombre neighbours, No 1 Poultry is ambiguous in both demanding acceptance but wanting to retain its uniqueness, with its puzzling yet unified facade, its bright colouring and Egyptian entry corridor," said Geoffrey H Baker in his book The Architecture of James Stirling and his Partners.

Despite Stirling's impressive reputation, the building was not widely appreciated when it was completed – it seemed the heyday of Postmodernism had passed. Critic Edwin Heathcote wrote that at the point of completion: "Postmodernism, the architectural style [No 1 Poultry] so perfectly represents and which reached its apogee in the 1980s, had slipped unceremoniously out of fashion."

Characteristically, Prince Charles described No 1 Poultry derisively as a "1930s wireless", while architecture critic Hugh Pearman compared the building to a hen. "Lots of people still cluck over Jim's fat hen at No 1 Poultry," he wrote. "I suspect this is because, deep down, they don't really like the idea of a modern building with the eccentric character of an earlier age. It is not pretty. It is not graceful. It does not integrate itself. It is definitely strange. But it exudes an astonishing sense of power and purpose. I admire it, but don't yet like it."

Stirling's partner Michael Wilford took a philosophical approach to the response. "Like it or hate it is a very common response to our buildings," he said. "There are very few people who are ambivalent about them. They confront in such a way as to force people to think."

No 1 Poultry struggled to find fans even before it was completed in 1997, with the site subject to one of the longest battles in UK planning history. The land was occupied by a group of much-loved Victorian buildings commissioned by silversmith company Mappin & Webb and the prospect of their demolition was met with fierce opposition. No 1 Poultry was commissioned by developer Peter Palumbo in 1985, but for over 20 years before that, Palumbo had been fighting to replace the listed buildings with an 18-storey glass tower designed by Mies van der Rohe.

Over time though, the building has become part of the fabric of London, and is recognised as one of the most important examples of commercial Postmodern architecture. But, like the Portland Building in the USA, its current owners – investment fund Perella Weinberg – are keen to update the structure for the demand of contemporary office and retail use.

They have commissioned London firm Buckley Gray Yeoman to overhaul the structure, with alterations including changes to the facades, entrances and windows.

Buckley Gray Yeoman partner Matt Yeoman told UK architecture site Bdonline, that the changes were of a "minor nature".

"There's a real concern that the tenants and occupiers won't stay and that the client will struggle to reoccupy the building if that happens," said Yeoman. "We like and respect the building and the architecture and we are just trying to adapt it to the changing needs of society."

Architectural preservation group the Twentieth Century Society is campaigning for the building to be protected with Grade II*-listed status – just like the buildings that stood on the site before. It has found support from a large number of James Stirling Michael Wilford and Partners employees, including Michael Wilford. Norman Foster and Richard Rogers have both written to the UK's heritage body Historic England objecting to the proposals, while the original developer, Peter Palumbo, has described the plans as "shallow, empty and of no account".

"The proposed alterations dilute the architectural design intent and risk chipping away at the wit and sophistication of this building which makes it stand out," said Catherine Croft, director of the Twentieth Century Society.

"This building is a playful, contextual masterpiece and a remarkable speculative office development from the 1990s. It is an outstanding example of Postmodern architecture, a style which is only just beginning to be studied and understood in historic terms. The assessment of this building for listing should trigger a re-evaluation of Postmodern architecture."

One of the biggest concerns is that the alterations could destabilise the public nature of the building. While No 1 Poultry's function was to provide five floors of office space, its public spaces provide a connection missing elsewhere in the City. They include open shopping colonnades on the Poultry and Queen Victoria Street facades, an open light-filled courtyard, a rooftop garden, and even access to the underground station below.

"[No 1 Poultry's] success comes from its accessibility, legibility and immense character – many thousands of people walk through the heart of the building every day glimpsing up to the sky or following the rain drops down to the concourse level some take the lifts which pop out like a cork from a champagne bottle in the middle of the oasis that is the public roof garden and enjoy the views right across the City," said Bain.

At the beginning of this month, Stirling's widow called on the City of London planners to reject the scheme in UK architecture magazine the Architect's Journal.

Zaha Hadid has also waded in, writing a letter of objection to the City of London's planners, refuting suggestions that the building is not as its architect intended it to be.

"Any suggestion that the building is not as James intended are spurious and can easily be proven untrue by Laurence Bain," she wrote. "We must surely all do our utmost to ensure that we do not destroy yet another beautiful example of Postmodernist architecture."

If the building is listed, it will be one of the youngest ever to be formally protected in the UK. In the meantime, the fight over its future has come to represent the battle to preserve Postmodern architecture before it is too late. No 1 Poultry has become a monument in the fast-changing cityscape, and London's Postmodern flagship.