Clients are increasingly attracted to designers who "think differently", while architects are restricted by knowledge says Dror Benshetrit – whose New York studio is developing a giant urban island off the coast of Istanbul (+ slideshow + interview).

Benshetrit, founder of Studio Dror, is among a small number of successful designers who are experimenting with large-scale architecture, including Thomas Heatherwick, Karim Rashid and Nendo founder Oki Sato.

"I definitely see more designers doing buildings today, and I think were going to see it more and more," Benshetrit told Dezeen. "The access to knowledge is changing, and access to specialists. It creates different discussions and different results."

"Many, many, many years ago creative people used to do more than just one thing. Education fragmented the arts into a lot of different specialised professions. And I see that changing back."

Benshetrit also suggested that contemporary education doesn't prepare architects for real-world building projects.

"I know a lot of architects that are not qualified to build anything," he said. "All of our architectural clients [have] been so proud to share with other people that I'm not an architect."

"[They think we] look at things differently. And I think it's true. Sometimes knowledge restricts you."

Benshetrit, 38, was born in Tel Aviv and studied at Design Academy Eindhoven in the Netherlands. At 25, he moved to New York and set up his studio in 2002.

For his firm's first architecture project – a 135,000-square-metre masterplan for a private island off the coast of Abu Dhabi – Benshetrit designed 24 beachfront villas covered by a blanket of grass.

"It was really about provoking a new typology in this region, really thinking about what luxury means, which evolved into this idea of creating this large architectural carpet," he explained. "Do you really need to be an architect by training to come up with an idea like that? Not necessarily."

His clients now range from fashion designer Yigal Azrouel through to Italian design brand Alessi, and American luggage company Tumi, but his best-known design remains the 2009 Peacock chair, produced by Capellini, which featured in a Rihanna music video. He has also developed a number of conceptual skyscraper designs for various property magnates.

Over the last two years, his firm has been working on a unique structural joint system, called QuaDror, and major urban-planning projects in Istanbul.

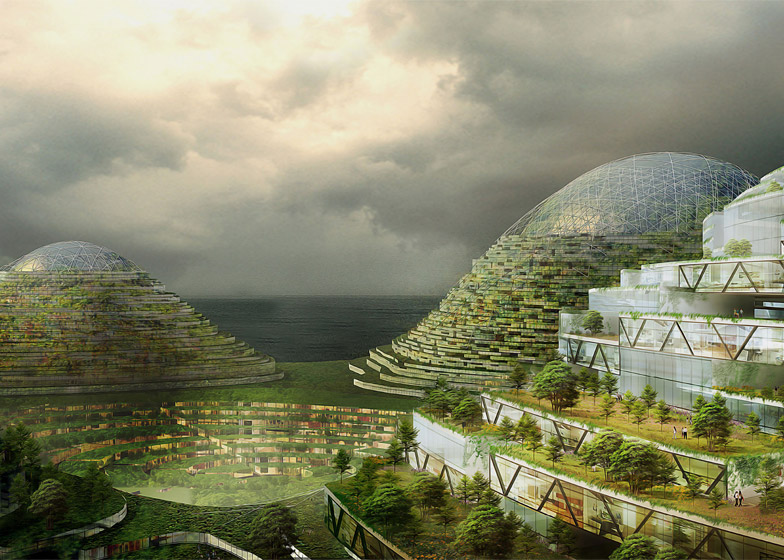

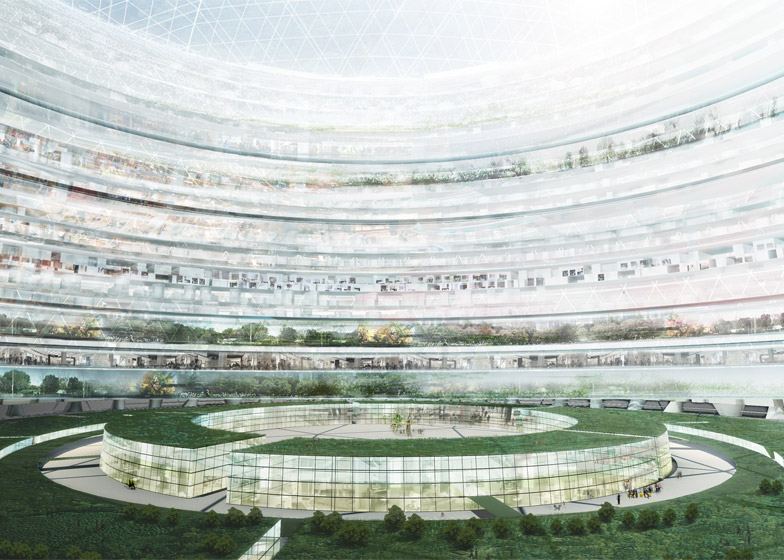

The biggest, called Havvada, proposes using the soil excavated from a canal under construction in the Turkish capital to create a new island off the coast. With a 16,535,000-square-metre masterplan, the island would consist of six "mega dome" hills and an inverted mound in the centre – all with buildings wrapped around them in levels.

"Whether it's built or not is almost not relevant, because the conversation is about the possibility of an urban grid being 3D instead of 2D," said Benshetrit.

Read an edited transcript from our interview with Dror Benshetrit:

Anna Winston: Do you think that not being a trained architect gives you an advantage?

Dror Benshetrit: Absolutely. I think that all of our architectural clients today, or actually ever since we've been practicing architecture, they've been so proud to share with other people that I'm not an architect.

They were like, well he just thinks differently, they do things differently and they look at things differently. And I think it's true. I think that sometimes knowledge restricts you.

Anna Winston: It does seem there are more designers doing building these days.

Dror Benshetrit: I definitely see more designers doing buildings today, and I think we're going to see it more and more. The access to knowledge is changing, and access to specialists, and maybe the different kind relationship to ego creates a new type of working relationship, which I think will create all kinds of new scenarios. It creates different discussions and different results.

Anna Winston: Is there ever a question about whether designers are qualified?

Dror Benshetrit: Nobody takes my sketch into construction. That's just not the way that it happens. Ideas – especially in architecture – take many phases and many forms before they get matured and ready for construction. So when you say qualified, it's truly a tough question. I know a lot of architects that are not qualified to build anything.

In every architectural project, we are adapting, we team up with an architect of record and we team up with a structural engineer, so we are always making sure that there are adults in the room.

The innovation very often happens in the structural system. Then we show it to engineers, we show it to architects, other partners, and that's how the dialogue grows. When we say we are an ideas-driven practice, it's really about that. It's about putting forward an approach and letting that seed of an idea grow into a very complex, interesting architectural project at the end.

Anna Winston: Do you think that you were one of the first designers that starting doing architectural projects like this?

Dror Benshetrit: Who else are you thinking about? Thomas Heatherwick is not an architect. He has been probably playing with architecture at similar times. I look at it as a way of thinking.

If you think about essentially our first built architectural project, and think about how this project started, it was really about provoking a new typology in this region, really thinking about what luxury means. Which evolved into this idea of creating this large architectural carpet, this large vegetated roof structure. Do you really need to be an architect by training to come up with an idea like that? Not necessarily.

Anna Winston: You said earlier that we might see more of this because designers can think differently.

Dror Benshetrit: We used to hear a lot of people saying we are a cross-discplinary design practice. I think a lot of that came because we realised that we need to protect a certain vision. When we designed Vase of Phases for Rosenthal in 2003, which was pretty much our first product in the market, we immediately asked Rosenthal, "well how are you going to package it, and who's going to photograph it, how are you going to display it in the store?" – because we felt that all of those different things that relate to other creative professions should be very much in line with our vision.

They basically turned the question back to us and said, "well how would you like to see it packaged, how would you like to see it photographed, how would you like to see it displayed? Could you help us come up with the name?" It's so interesting to be the creative director if you can work on those kinds of projects. It starts to evolve into having no boundaries in creativity.

Architecture was just an evolution after interior design. With my very first interior project, the Yigal [Azrouel] store in the Meatpacking, it was pretty much the same story. The client said "well, you're a product designer, not an interior designer". But by showing him that we have a certain vision that fits into how he would like to translate clothing into a space, we could actually create that kind of translation for other kinds of projects and different scales.

I think that trend is something that probably would be more and more evident in people that think conceptually first, people that have a certain ideology with their design. It's very often about creating opportunities. I know a lot of designers today that if you asked them are you interested in making a building, they would say absolutely yes.

Many, many, many years ago creative people used to do more than just one thing. Education fragmented the arts into a lot of different specialised professions. And I see that changing back. I think it used to be more common in the past.

Anna Winston: Why did you decide to be based in New York?

Dror Benshetrit: I actually moved to New York first in 1998 before going to school, before I even committed to design – when I was still an artist, thinking that maybe I should check what design was all about. I came to New York looking for schools and very quickly realised that I didn't want to study here. I wanted to be in Europe.

But there was something in New York that attracted me. I think it was the melting pot, this extreme cultural hub for art and architecture. Later on, when I realised the gap between what we consider contemporary in Europe and what we consider contemporary in the States, I felt the need to minimise that and to be here for that. This country is fascinating on so many levels, but there is a a major gap.

Anna Winston: There are a lot of very big established names in the city, in architecture in particular. Do you compete with that?

Dror Benshetrit: The word compete is an interesting one. We are competing, but there is also a conversation – spoken and unspoken – between the work that is being done here.

I'd take it a step back before calling it just an aesthetic. The conversations are changing very fast – we are not the only ones in New York that talk about innovation, that are talking about changing the rules of the game.

New York has been redefining the definition of luxury over the past 10 years, multiple times. We have spoken about luxury different in 2007, in 2009, in 2012 and we speak about it differently today. Those are conversations that are happening in New York, but are not happening as much in Milan, they are not happening as much in Malaysia, they are not happening as much in Switzerland.

Anna Winston: Is that because the market is very developer-driven and there is less public work?

Dror Benshetrit: No. I think the market here looks more towards tomorrow than towards yesterday, maybe? The fashion world is very prominent in New York and fashion is constantly thinking forward. We are surrounded by that.

[But] it's very hard to avoid the financial dialogue in design. The rent we pay, the construction costs, the prices of raw materials – these are all getting higher and higher. It creates a certain vocabulary, and a certain kind of globalisation, global thinking, which is also very interesting.

What is missing here is a bit of product design. Since I started my practice I have not worked with an American furniture manufacturer.

Yes, we have worked with American companies like [luggage manufacturers] Tumi. But I'm speaking specifically about the furniture, and for that we've worked only with European brands. The type of things that we care about – the aesthetic, the quality, the conversations around those kind of pieces – are more with the European brands.

It never even occurred to me "oh, if you're using so many European companies, why are you in New York?" Because I think this world is bigger than that. If we would have only done furniture – yeah. Why would I travel back and forth? But if you're talking about a more holistic approach to design, it makes sense for us to here.

Starting your own practice, being stubborn not to go and work for anyone else because you don't want to change your natural behaviour – to become a protege of someone else – is something that I cared about. I didn't go to business school and I didn't study law. I didn't study all those things that are required when dealing with products and interiors and architecture. But in New York you can learn those things.

Anna Winston: Your latest projects use a new geometry you've been developing. Can you explain how that came about?

Dror Benshetrit: The invention itself, the basic geometry happened in day, but it took me five years to understand it! [QuaDror] is a new type of hinge, basically. It's not a hinge that works on a 2D axis, on a single axis. It has a diagonal axis, so the rotation point is circular – which makes a very weird angle in the pieces. So we needed to create parametric software that took us a year to programme for all kinds of different applications. It could have acoustic benefits, it could have tremendous load-bearing capacity.

We decided to debut it and share it with the world. We have learned a lot from that. Like how do we licence it? Licensing deals in the furniture world are completely different than in the infrastructure world or the architecture world, so we've exhausted ourselves. So we decided to take a few steps back, we said OK let's really understand what we've done.

Anna Winston: How much of your work is product design and how much of your work is architecture?

Dror Benshetrit: It really depends. Two years ago we won two very large architectural commissions. Those projects are in Istanbul, and I realised I had to let something go and put some stuff on hold in order to do this right. So the ratio changed overnight and we had to put a lot of product projects on hold.

Now the ratio is starting to shift back and change and we will be doing more products, but in a very different way. Two years have passed by. Things have changed in Italy a lot and therefore the conversations have changed. The approach to innovation has changed.

New players are coming in. Some people are deciding to do their own production and their own products because they don't like the structure or they don't like having no freedom or control.

When we debuted the Peacock Chair, simultaneously we debuted a collection for Target and chose to present them side-by-side. It was like, well you can buy this entire collection a hundred times and still not be able to afford that chair! The Target collection did extremely well and sold extremely well. While, the Peacock Chair received a lot of attention and was added to the permanent collection of the Metropolitan [Museum of Art]. So what's more important? I think the answer is both.

The week that the chair got accepted into the Metropolitan, Rihanna used the Peacock in her music video, so you can also ask yourself – "well 40 million people saw this chair on Youtube in one week, while 300,000 visitors a year visit the Metropolitan. What is more important?" The way we look at culture and the way we look at cultural contribution changes everyday. Everything is relevant and everything is appropriate in one way or another.

Our first international commission resulted in a billion-dollar sale. I never went to architecture school but I realised the power of ideas. How does that trickle down to some of the product designs that I have done in the past? Are they as important culturally?

And then this project – the conceptual city in the water outside of Istanbul – changed my perception again. Can we have a simple idea that can be the catalyst for a new urban model? The answer is yes. Whether it's built or not is almost not relevant, because the conversation is about the possibility of an urban grid being 3D instead of 2D.

When you think about those things, you can begin to put them into perspective with some of the other stuff. What we've done is not just design, it's changing the way people use luggage – the fact you can change your backpack and make it look like a tote bag that looks like nothing like your backpack when you step into a meeting or when you would feel stupid carrying a backpack to an event right after the gym. I think that that is an improvement for your wellbeing. That conversation for me is as important as thinking about urban planning.

Anna Winston: But the projects in Istanbul are huge, urban-scale things, while the projects in Italy or here are much smaller – they're different things.

Dror Benshetrit: But they are as meaningful sometimes. When I went to school in the Netherlands, someone left a really, really, really nice knife in our apartment. Before that I had never owned a really good knife. All of a sudden I realised that I enjoyed cutting vegetables so much more, that I consumed a lot more and became a lot healthier. All because I had a better knife! That for me is part of the conversation of wellbeing.