Sci-fi movie Back to the Future II created a "self-fulfilling prophecy" that helped shape today's interactions and objects, according to contemporary designers.

"When you imagine the future it brings it closer," says Matt Cooper-Wright, a project leader and interaction designer at innovation and design consultancy IDEO. "It becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy once it's out there in the collective consciousness. It gets into the brain of a young kid who then grows up to be a scientist or a designer."

"The ambient nature of those things means that even if you're not actually pursuing it, it's there – it's partly possible, partly that bit closer."

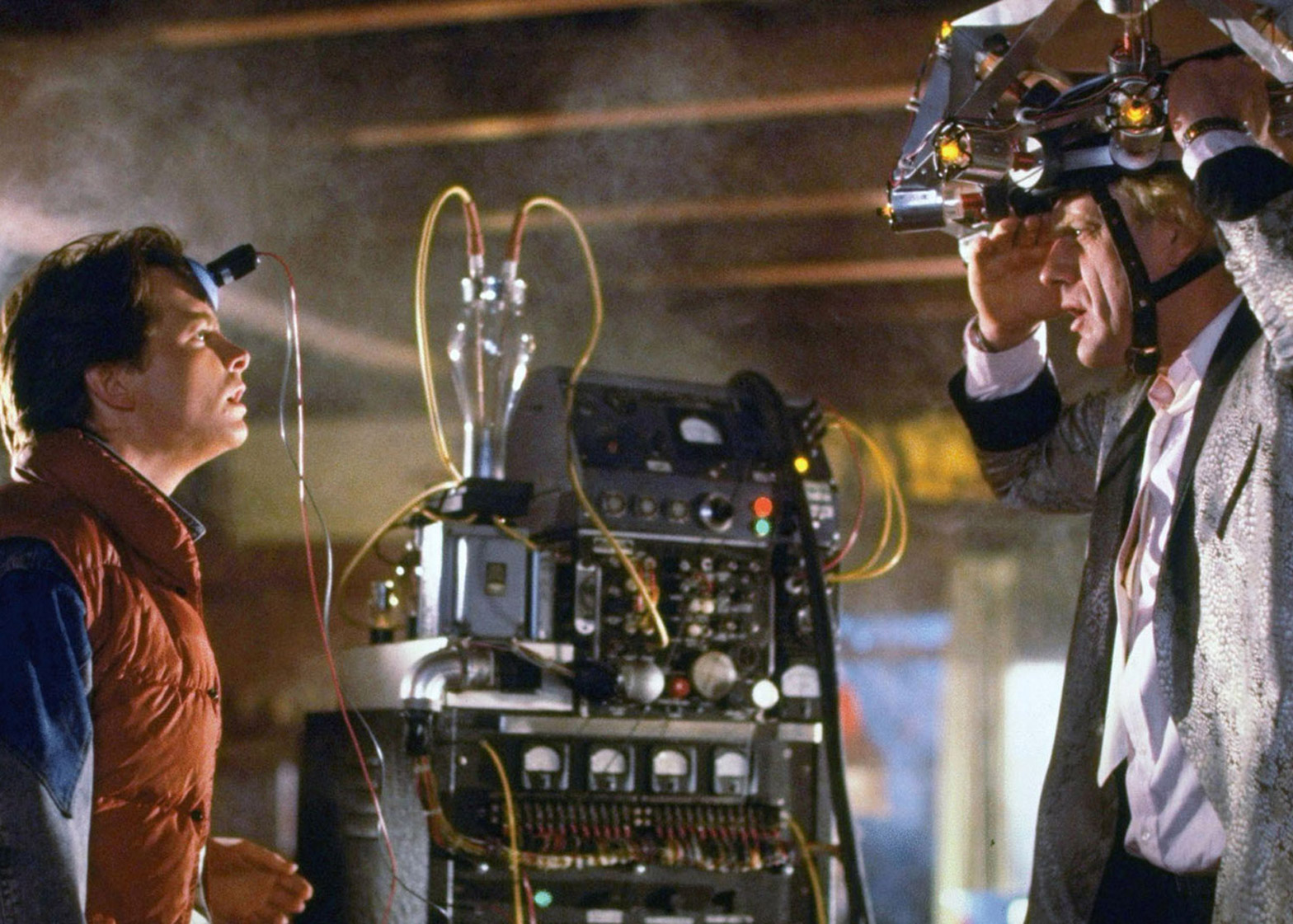

Fans of the 1989 movie will already know that today, 21 October 2015, is the day that Marty McFly, played by Michael J Fox, and mad-scientist inventor Doc Brown, played by Christopher Lloyd, travel to from 1985 – where the pair find themselves in a futuristic world where cars fly, skateboards hover and robots perform daily tasks.

In fact, it's hard to escape – almost every media outlet is publishing an almost identical listicle covering the parallels between predictions made by the film and today's real-world technologies and designs.

This is partly thanks to the ongoing popularity of the movie, which has proven to be the most enduring classic from the short-lived teen comedy sci-fi genre (see also Weird Science, in which two "nerds" create the "ideal" woman via an exploding computer).

But it's also because Back to the Future's vision of 2015 – from finger-print activated payment devices to video-calling, augmented-reality glasses, wearable tech and intelligent home appliances – has proven surprisingly prescient.

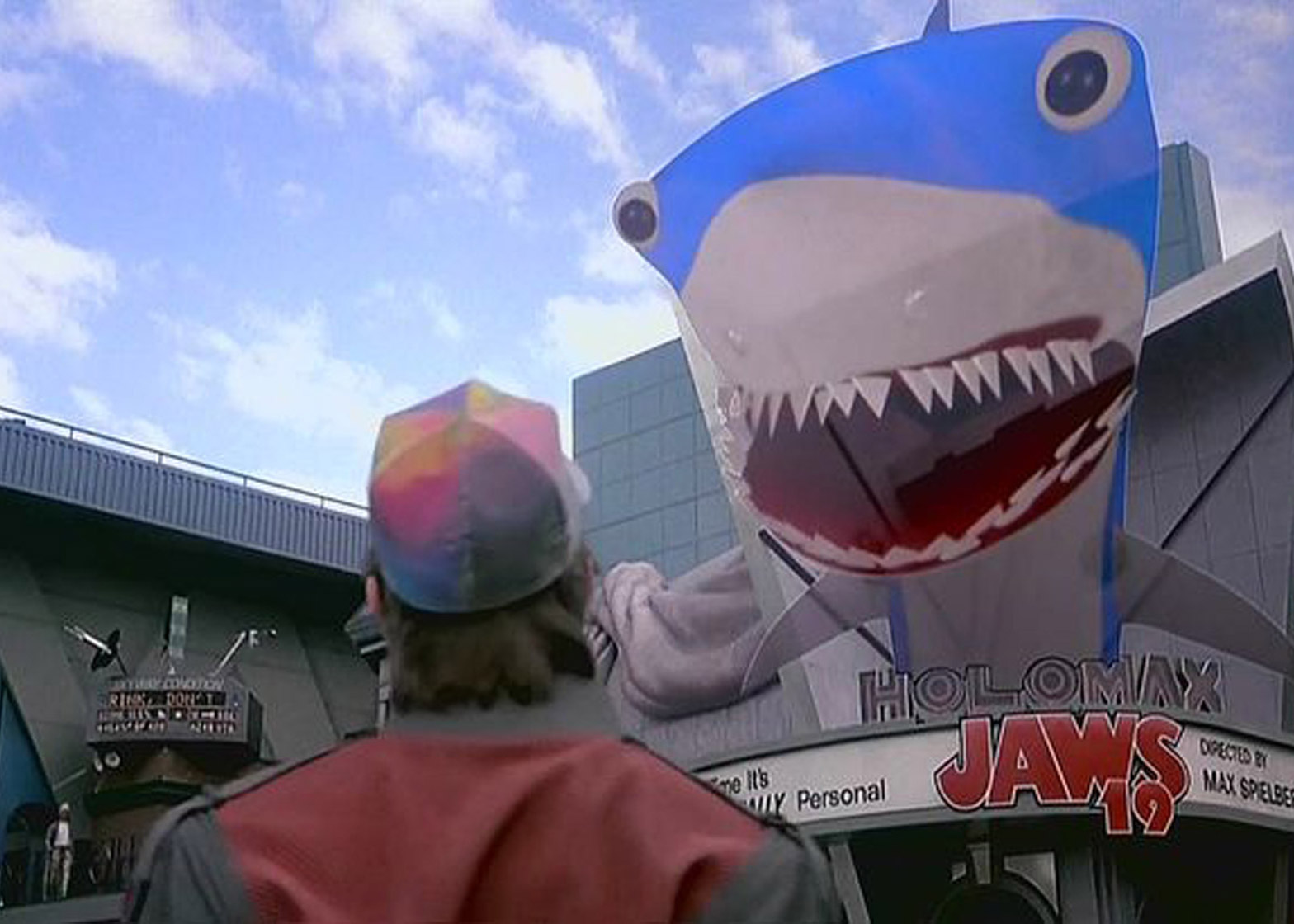

Examples of the designs and technologies that feature in the film and have become, or are almost, reality include holobillboards, hovercams (aka drone-mounted cameras), and wearable technology – from Marty Jr's talking jacket, to the police officers' ticker-tape hat signs.

"There are many concepts within Back to the Future that we're seeing realised today – things like hovercrafts, robots, a bit of augmented reality," said Yves Behar, founder of San Francisco studio Fuseproject and the designer behind various products including connected thermostats, Jambox's wireless speakers, and the UP activity tracker.

Behar's recently updated August Smart Lock system – replacing physical keys with a smartphone app – mirrors another technology predicted in the film, which features computer-operated and fingerprint-responsive locks. Google-owned domestic technology firm Nest recently teamed up with security firm Yale to launch a similar product.

"I'd argue that these types of films do not guide design, but rather, they represent ideas that are pre-existing in our culture," said Behar. "The technology develops as people become cognizant of new ways of inventing. The designer's job is to ensure that the utopian aspects of these ideas come to life... and that the dystopian Hollywood predictions stay on the screen where they belong!"

The film's Mr Fusion Home Energy Reactor, a domestic energy producer that runs on rubbish and is adapted to power the protagonists' time machine, may not be in our homes, but we are in the early stages of converting rubbish into fuel. Fossil fuels are certainly no longer the focus for the future – we're much closer to using electricity or even water to power our vehicles and there are also concepts floating around for harnessing the power of methane.

Video calling has become common-place with Skype and FaceTime, while the film's portable thumb units – used to take payments by scanning thumbprints – echo Apple's finger-print-operated security systems. And then there's the video glasses, which have clear parallels in augmented- and virtual-reality devices like Google Glass and Oculus Rift.

Many of these only appear fleetingly in the film, and some of them are clearly meant to be jokes, but they create a holistic future environment that is easy to recognise.

Other designs and technologies in the film aren't quite ready yet, but don't feel absurdly unrealistic. Earlier this year, Ikea and IDEO unveiled a concept for a "smart" kitchen table that offers a contemporary take on the film's Master-cook device – a wall-mounted machine designed as an intelligent kitchen aid. While bionic implants have a long way to go before they become widely adopted, we do have the world's first officially recognised human cyborg in Neil Harbisson, and implants could eventually replace wearable tech.

"There are some details from the experience of everyday life as depicted in the film that we leapfrogged," said Carla Diana, a US-based designer whose work focuses on future concepts. "For example, fax machines and laser discs are featured in the film's future, but these are woefully outdated to us now. Nonetheless, I do think the film has influenced design and design futures."

Designers have mixed opinions on how the film's production team managed to get it so right, and why they got some of it wrong. One of the hardest things to predict was the internet, hence the presence of the fax machines, CDs and a pay phone.

"My favourite thing in that movie is the way the headline on the front of the newspaper changes as evidence of all being right with the world," said Kieran Long, keeper of the design, architecture and digital department at London's V&A museum. "It's just about true that newspapers still exist in 2015, but in a few more years you'll have to explain what a newspaper was to children who watch it."

The "future fashion" worn by the "bad guys" in the film is laughable – although the fact that some of the clothes in the film can self-adjust and self-dry no longer seems outlandish.

According to fashion curator Sofia Hedman, its not unusual for sci-fi films to have a role in shaping what we wear.

"It is fascinating how popular culture and its visions of the future sometimes seem to actually form the future," she said. "This intriguing relationship goes back a long time. In Jules Verne's From the Earth to the Moon (1865), clothing and technology enable the characters to go beyond the human condition and reach the moon. Characters in comics and films of the 1930s often had glass helmets and oxygen tank space suits that were remarkably similar to the real ones designed for space flight decades later."

Like many earlier sci-fi narratives, Back to the Future II has an obsession with flight. But flying cars, despite some stirling efforts, are not much closer to becoming a familiar sight in our skies.

"I don't think anybody really thinks about the reality of how complicated flying anything is, let alone in a confined space like a city. So it's not surprising it hasn't happened," said Cooper-Wright. "It's more surprising that people are still hanging onto it, like this is something we should have – this retro view of the future."

There have also been a few frantic attempts at trying to realise a working hoverboard in time for Back to the Future day. Lexus launched a functioning version earlier this year, while Hendo has unveiled its second model to coincide with the date.

But as with flying cars, the results thus far aren't particularly convincing – relying on magnetic forces that would require the repaving of entire urban environments to work – and low-tech skateboards are enjoying a bit of a revival instead.

Earlier this year, sports brand Nike also teased plans to produce a real version of the self-lacing shoes first created as a prop for the film, although a release date has yet to be revealed.

"The effort to develop these is based on a fantasy of the future no doubt influenced by the film," said Diana. "I don't see great value in the hovering capability beyond marvelling at the magic of technology and its ability to give us a sense of mastery over gravity, one of nature's core constraints."

"The idea of autolacing sneakers has appeared in fashion a few times since the film. This idea actually drives me a little bananas since I think lacing shoes is an inherently old-fashioned activity," she added. "Certainly the future would have given us shoes with air valves or electromagnetic sutures, right? Or how about taking some of that hovering tech and giving us hoversoles so we don't even need shoes at all?"

What the hoverboard provides in the film is a neatly recognisable connection between the past and the present – an obvious update to the skateboard – that allows the film makers to echo a scene from 1985 in 2015 but make it obviously "the future".

According to Cooper-Wright, this is key to how the film's production team managed to make so many of the other more ambient designs appear so accurate. Rather than pepper the set with hundreds of computer screens, like so many other sci-fi films, they looked at how familiar objects from 1985 might evolve.

"There's a lot of technology that's not really making a big show of itself in the story-telling – small devices and objects in the environment," said Cooper-Wright. "When you watch the film, the technology changes but the behaviour doesn't."

This approach to story-telling – making the future recognisable enough to seem tangible to the general audience – may hold the key to integrating new and ever-developing technologies into everyday products and interactions.

"More and more of the technology that affects the way our world works is being more and more invisible," says Cooper-Wright. "Physical objects in sci-fi films make the story-telling easier, and there are stories to be told about the way you use services like Uber, so how do we design those things in?"

"How do we think a bit more like film makers to communicate all that complexity through something that is not complex in itself? It's a big challenge. The skills of the film maker and the editor are becoming skill sets that designers needs to have as well."