Rising sea levels and a shortage of development sites are leading to a surge of interest in floating buildings, with proposals ranging from mass housing on London's canals to entire amphibious cities in China (+ slideshow).

People will increasingly live and work on water, as planning policies shift away from building flood defences towards accepting that seas and rivers cannot be contained forever, say the architects behind these proposals.

"Given the impact of climate change, we can begin to think a lot more about the opportunity for living with water as opposed to fighting it and doing land reclamation," said architect Kunlé Adeyemi.

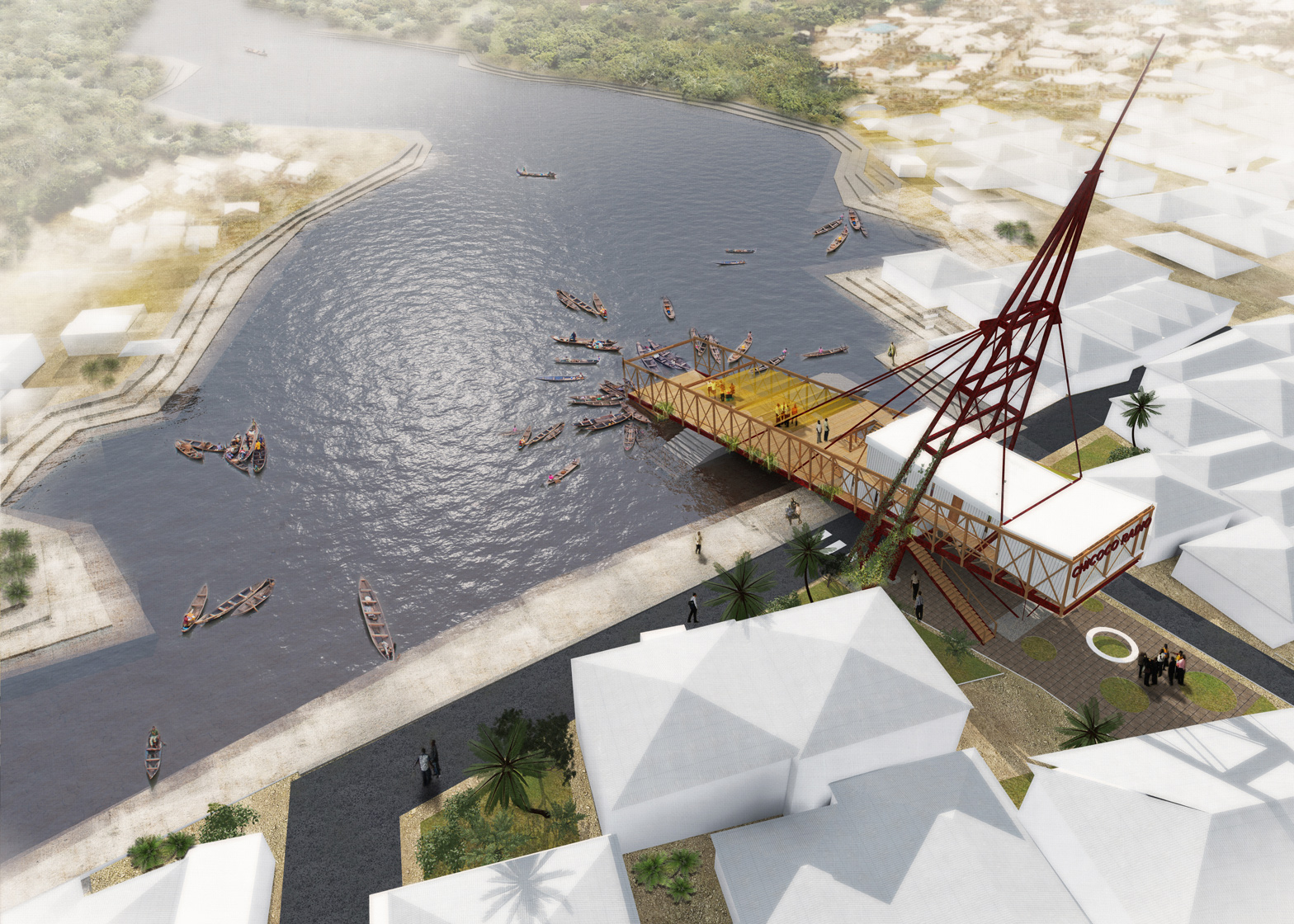

Adeyemi, who is founder of Dutch studio NLÉ, has already designed several aquatic buildings in coastal Africa, including a floating school for a Lagos lagoon and a radio station in the Niger Delta. The pair of buildings are prototypes for part of a larger research project called African Water Cities, which aims to create new infrastructure in waterside areas.

With over a quarter of its land mass lying below sea level, the Netherlands, where Adeyemi is based, leads the world in water management and has developed sophisticated planning policies that encourage water-based living.

Colonies of floating houses have sprung up along Amsterdam's river IJ, in a development that is forecasted to provide 18,000 new homes to help stem the city's housing shortage. MVRDV also recently unveiled plans for a tennis club in the new neighbourhood, which is being partly constructed over reclaimed land.

Further inland, boxy houseboats are moored along the edges of the city's multitude of canals, some with their bases partly submerged in the water to provide extra living space.

"We know that the policies are a little more advanced than in other parts of the world because they've been doing it for several years," Adeyemi told Dezeen. "Policies [elsewhere] require some improvement."

Dutch water management specialists have been drafted in to advise on policies in Indonesia, America, Britain, Mozambique and Ethiopia. The architect said the rest of the world now needs to follow suit.

Tracy Metz, a Harvard fellow that has spent years researching architecture and infrastructure strategies that integrate water, believes the change is already underway.

"You see that the design in our cities for water is really one of the drivers of urban design and architecture now," said Metz, speaking at the What Design Can Do conference in São Paulo this week.

"It's about making the city flexible," she added. "How do we use these spaces that sometimes are wet, sometimes are dry?"

In 2012, Alex de Rijke from London firm dRMM called British architects to look to the Netherlands for a solution to the UK's housing crisis: "There is no shortage of water in the UK and no shortage of rain," he said, "but there is a shortage of housing and a shortage of development sites."

Since then, other British firms have proposed replicating the floating homes of Amsterdam's canals on English waterways.

London architect Carl Turner believes thousands of homes and workplaces could be stationed across the UK's disused waterways. Earlier this year he released plans for a floating house on an open-source website.

Turner said that floating buildings make sense, not just because of climate change. "In areas with a huge housing shortage like London, there are obviously still huge opportunities on canals and river edges," he said. "There are huge areas of docks in the east end where you could fit hundreds if not thousands of homes."

Another London firm, Baca Architects, completed the UK's first amphibious house in 2014 and recently designed a series of prefabricated houseboats for the capital's waterways, working with a Dutch manufacturer.

"Designers need to create adaptable forms of architecture that respond to the uncertainty of future change," explained Baca co-founder Richard Coutts, who also believes "aquatecture" can provide some of the 440,000 new homes needed to alleviate London's housing problem.

"Flooding is likely to increase in frequency, severity and intensity," he said, also adding that UK architects could learn from the Dutch. "Intuitively we have been taught to hold water out rather than let it in," he said. "The Dutch have embraced living with water as they have had no choice."

The firm recently won an ideas competition to populate the capital's waterways with buoyant homes, suggesting that 7,500 affordable prefabricated dwellings could be installed in the 50 miles of rivers and canals in Greater London.

But Coutts said Europe's "ad hoc and absent" planning policy is a constant stumbling block and needs to be brought up to date as the risk of global flooding increases.

"The design community awaits the necessary support from planning policy to be able to deliver wholesale and safe aquatecture," he told Dezeen.

However Matthew Butcher, a lecturer at London architecture school the Bartlett, told Dezeen that architects should be wary of simply replicating the Dutch houseboat model.

By permanently mooring the structures to land, he believes they fail to ask fundamental questions about how the environment is changing.

"One of my issues with floating houses is that they just tend to look like houses that happen to have been put on the water," said Butcher, who is currently working on a floating weather station that he will launch into the Thames estuary as part of a research project to monitor the fluctuations of the tide.

"With these floating houses in Holland, you don't really have to change the way you live," he added. "They tend to be presented in a very positivist light. It's like 'isn't it great we have the technology to do this, we don't have to worry about the environment anymore'."

Adeyemi agreed, saying waterways are often considered as a "backyard where waste is dumped" rather than an asset, but predicted that climate change would force people to start reconsidering their relationship with water.

"If focus is turned back towards this asset, this natural resource, we could start treating it better and improving the condition of the waterways," he said.