Landmark buildings and experimental construction are transforming the Netherlands' second city into a world-class destination for architectural innovation, outstripping other European centres and turning Amsterdam into "the city of the past".

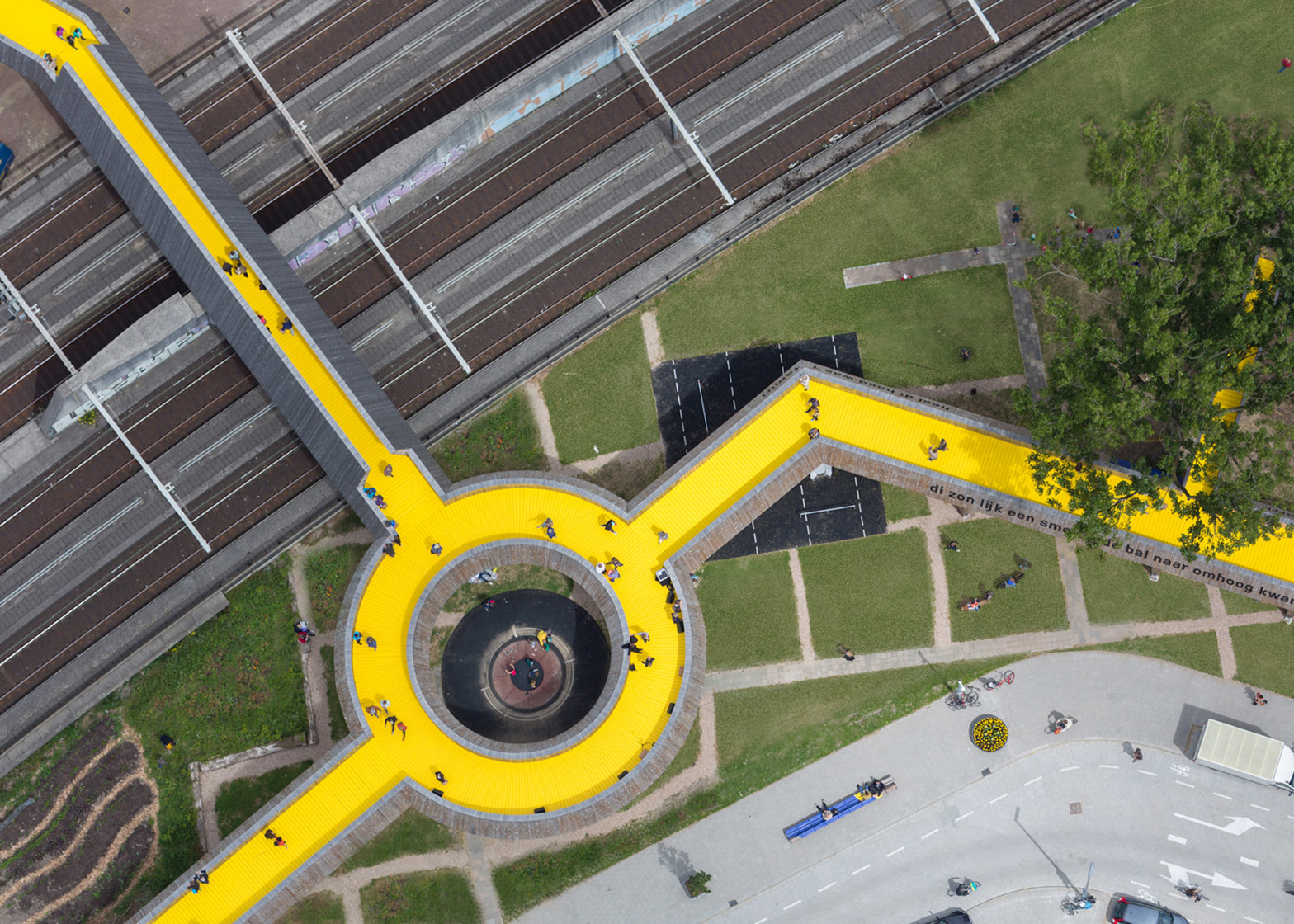

In the last two years Rotterdam's cityscape has seen the arrival of several major buildings, from MVRDV's colossal market hall to OMA's towering De Rotterdam hotel and office block and the new railway station by Benthem Crouwel, MVSA and West 8.

But it has also established itself as a hub for new building technologies, home to studios experimenting with floating architecture, robotic construction, wind power, lighting innovation and 3D printing.

All this despite having been one of the worst-bombed cities during the second world war, when most of the city centre was reduced to rubble.

"The city has had a remarkable turnaround in the last 20 years, and architecture is playing a big part in it," said Reinier de Graaf, who grew up in Rotterdam and is a partner at OMA, which has been based in the city since Rem Koolhaas established the firm in 1975.

"It is becoming a centre for architecture," he told Dezeen.

MVRDV co-founder Jacob van Rijs – also based in Rotterdam – echoes the sentiment. "There is a buzz," he told Dezeen. "The new architecture has been coming a long time, but now that things are realised for the outside world to see, Rotterdam is in the spotlight."

"It was always really behind Amsterdam," he added. "But people are now seeing there's another city and that it's actually pretty interesting. We're really proud of that here, people sense this optimism."

Rotterdam's newfound status as a city of the future was affirmed by its inclusion in Lonely Planet's list of the top 10 cities to visit in 2016, where it was was described as "a veritable open-air gallery of Modern, Postmodern and contemporary construction".

"There is a tradition of innovative architecture in Rotterdam and this is something the city marketing has also picked up on," said Duzan Doepel, another Rotterdam-based architect.

"Amsterdam is the city of the past, Rotterdam is the city of the future, and that's something that we can build on," he told Dezeen.

Doepel emigrated to the Netherlands from South Africa to work for MVRDV, and the liberal approach to architecture in the city kept him from returning home.

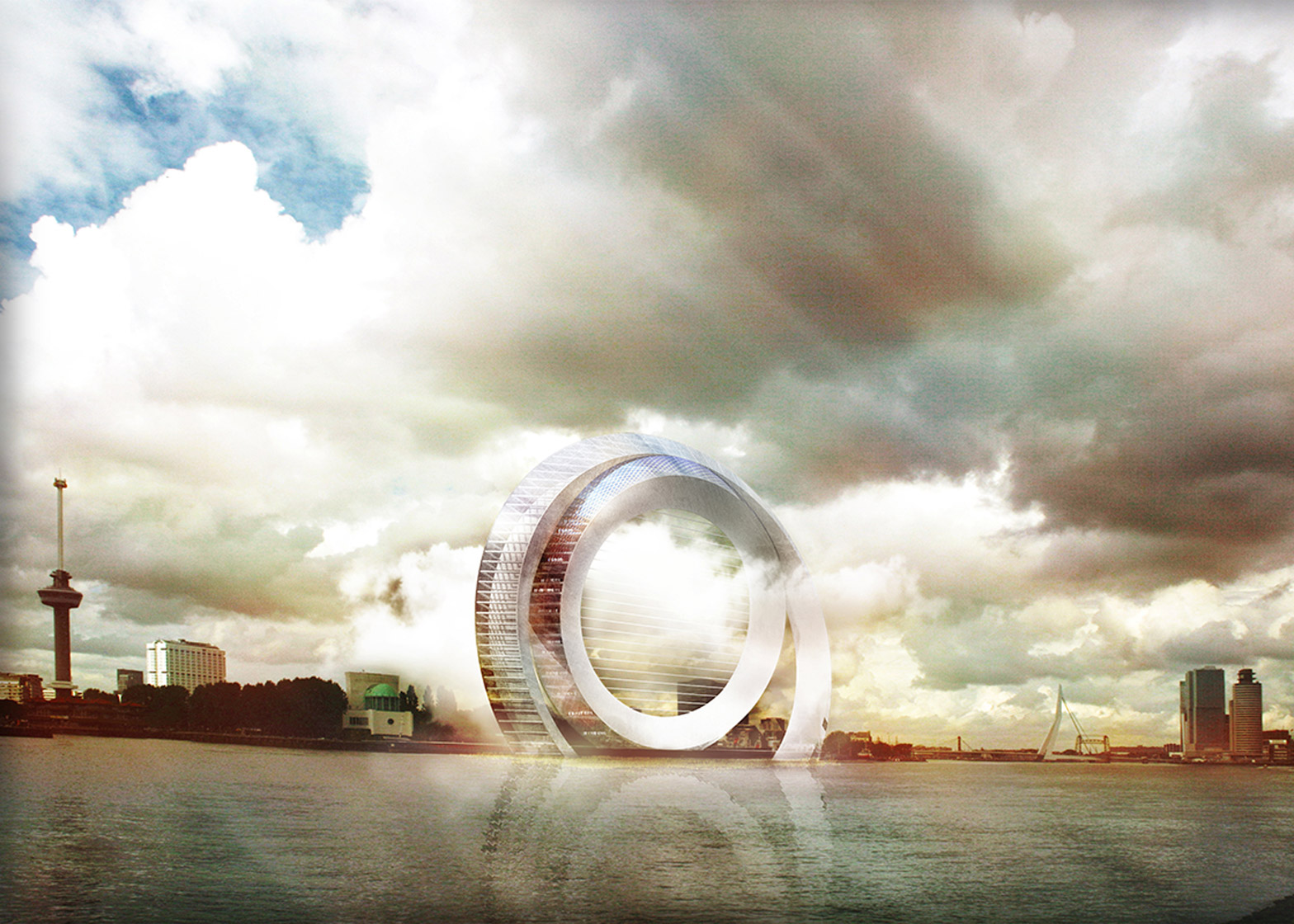

He and fellow architect Eline Strijkers set up their own studio named Doepel Strijkers in 2007, and last year unveiled a conceptual design for a huge circular wind turbine that doubles as an apartment block and hotel for Rotterdam's waterfront.

Despite being way ahead of current technologies, the proposal has the backing of the city government. Doepel believes this support has been pivotal in establishing Rotterdam as a centre of design for the future.

"There is so much innovation happening here, it's unprecedented, and it's hard to challenge it," he added. "The question is how to channel that and ensure that projects keep happening here."

During the second world war bombings of 1940 and 1943, the city lost over 26,000 homes and more than 6,000 other buildings. So unlike Amsterdam or The Hague, there is very little old architecture to preserve and respect in Rotterdam.

It is this lack of historical context, according to De Graaf, that has transformed the city into a testing ground for new building styles, with radical early examples including Piet Blom's Cube Houses, built in 1977, and Marcel Breuer's De Bijenkorf department store of 1957.

"Here you can experiment, because there's not that much you can ruin," explained De Graaf. "When you work in a historical city like Venice, Amsterdam or St Petersburg, people there are precious about their city and rightfully so, there are centuries of history."

"But in Rotterdam, there is a different architectural vogue every 10 years," he added. "It is an ecology of successive architectural convictions, and the sum total of these convictions – however firm they were – is of course a certain degree of improvisation."

"So in that sense there is an amount of intellectual freedom and a kind of footloose, un-dogmatic, free-floating situation to work in, and it means the mentality of the people in Rotterdam is not conservative at all."

De Graaf recently completed the city's new Timmerhuis – a mixed-use building with a pixellated steel and glass structure, which houses a museum, council offices, apartments, shops and restaurants.

"The building is a mirror for the city's present improvised state," he said. "There wasn't a prevailing context for how things should be done, we had an enormous freedom to do whatever, although it is our hometown so it had to be good!"

Meanwhile, Van Rijs credits Rotterdam's current success to a government initiative to sell off old dilapidated houses at low prices, on the agreement that new owners invest a set amount towards renovation works.

"You could get a house for a small amount of money, turn it into something special, and then find yourself in a neighbourhood with a lot of people who have done the same thing," he explained. "This encouraged people who would normally leave the city to stay, and there is much more interest in living in the city."

Following the success of the Markthal, Van Rijs' firm is working on another project in Rotterdam – a bowl-shaped art depot for the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen with a mirrored exterior and a rooftop sculpture garden.

"There has never officially been a moment where Rotterdam was branded as an 'architecture city', but you could say that it is right now," he added. "Whereas 10 years ago Amsterdam was the architecture city, now it's here."

Rejuvenating the housing market isn't the only government initiative that has contributed to economic growth.

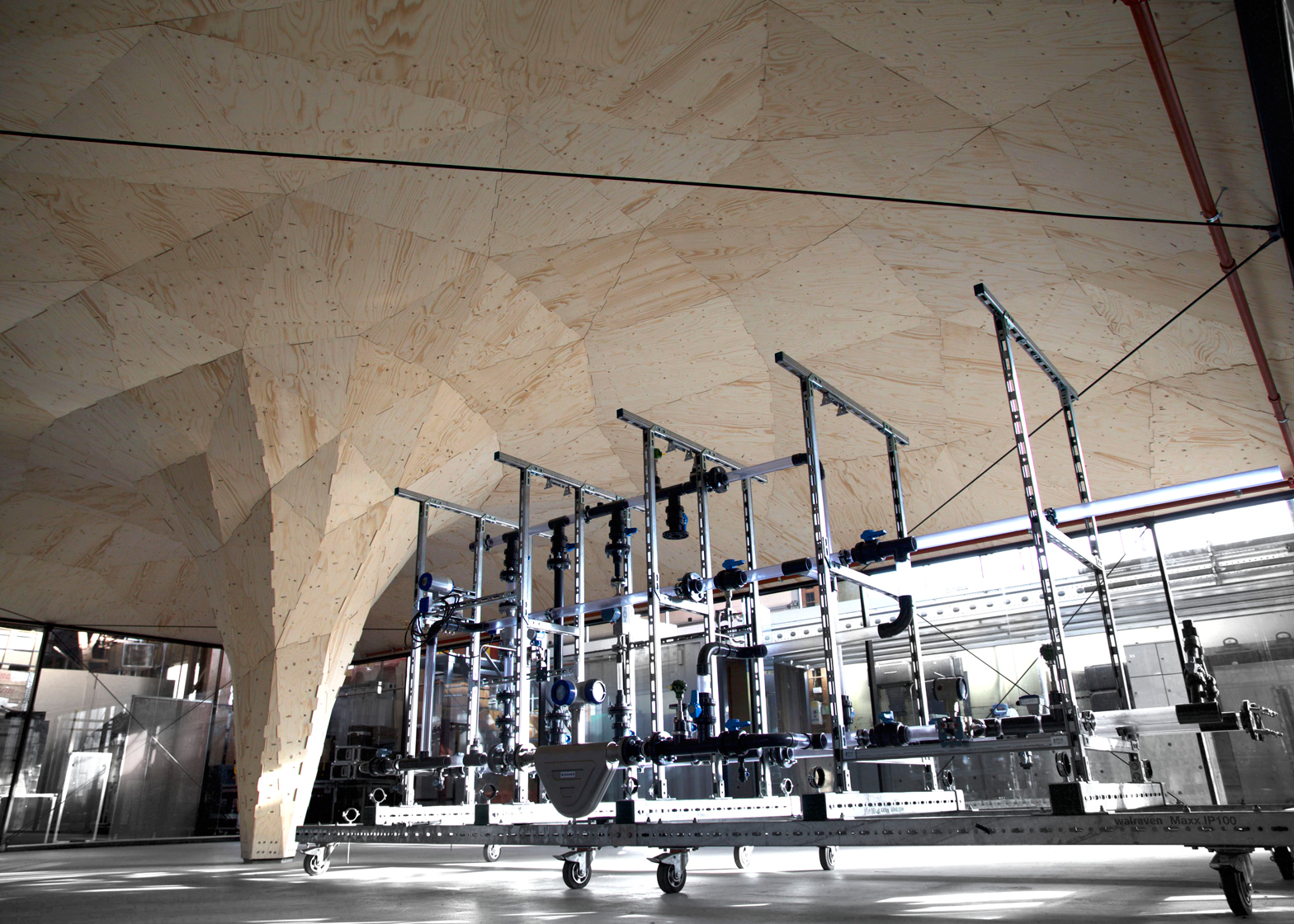

In 2002 the city acquired the former shipyard of the Rotterdam Drydock Company and transformed it into RDM Rotterdam – an innovation campus accommodating both startups and students from the Rotterdam University of Applied Sciences.

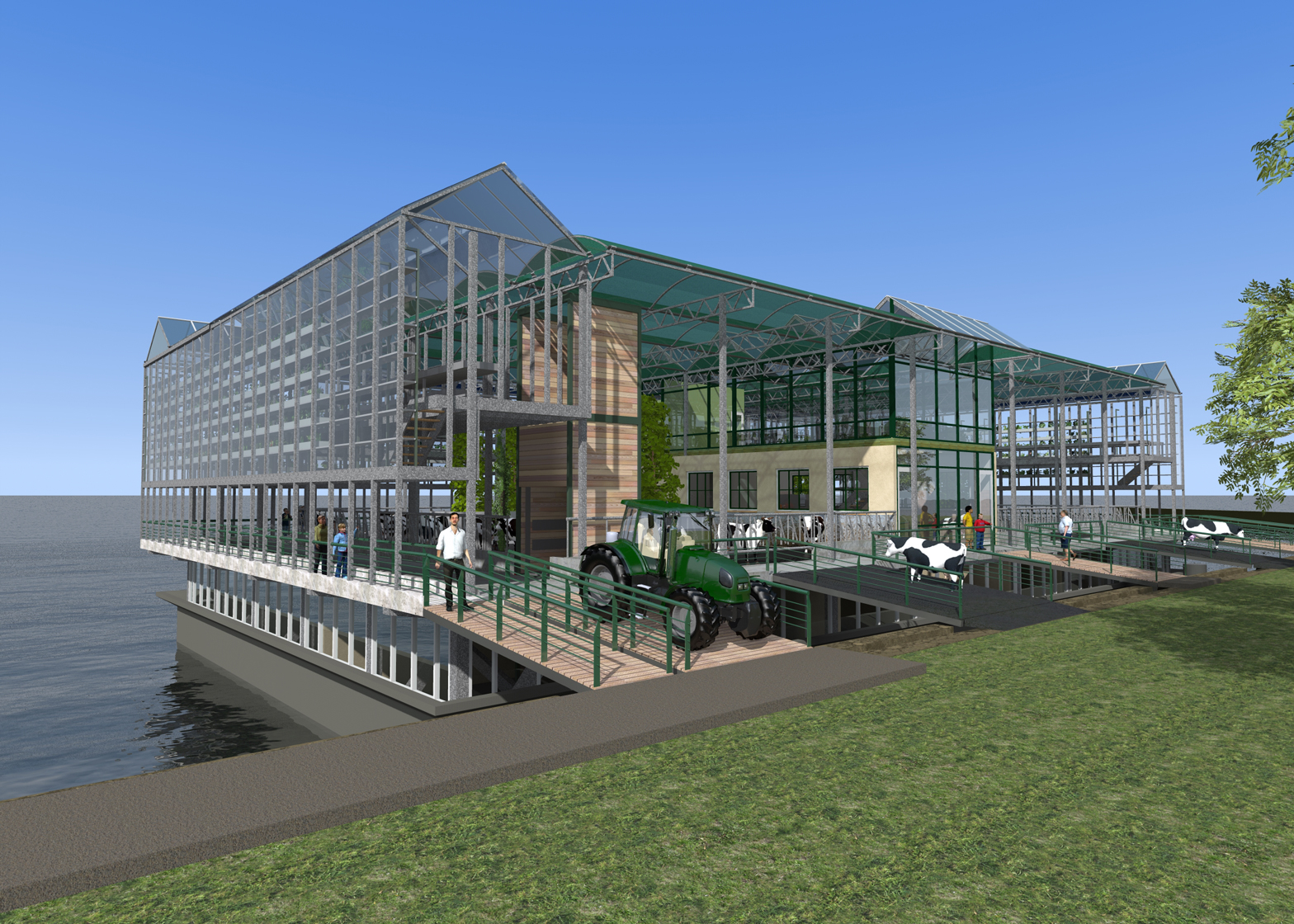

RDM's aim is to become a centre of expertise for a broad spectrum of new technologies. For instance, design office Studio RAP recently built a 130-square-metre building there using a robot, while designer Jorge Bakker is trialling a prototype for a floating forest outside.

The city has also targeted a number of pioneers to bring to Rotterdam, joining design figures already established in the city like Richard Hutten, Joep van Lieshout and Jurgen Bey.

Among them was designer Daan Roosegaarde, who has worked on numerous visionary ideas including glow-in-the-dark roads and a smog-purifying tower.

"We were looking to move and Rotterdam contacted us very specifically," the Studio Roosegaarde founder told Dezeen.

Roosegaarde has installed the first prototype of his Smog Free Tower outside his new Rotterdam office. He believes that projects like this will be key in cementing the city's reputation as a centre for technology.

"For me it's not just about building more buildings, but about adding another layer of information and experience to a city," he added. "For example, why can we not connect all the existing streetlights to simple sensors, so that the streetlights go on where you walk, and off when you're not there? These are the new types of icons we're talking about."

According to Roosegaarde, there will be more and more built projects popping up over the city in the next 10 to 15 years, a mix of both government-funded schemes and bottom-up developments.

"Rotterdam is, in my opinion, the city with the most courage and curiosity to explore the new world," he said.

"They have a strong emphasis on creative industry and new thinking," he added. "They show some guts and are willing to invest in new ideas, not just out of enthusiasm, but because it is super necessary to keep the city healthy and futureproofed."

See more of the architecture projects helping to transform Rotterdam »