All architecture needs a humanitarian approach, says Jacques Herzog

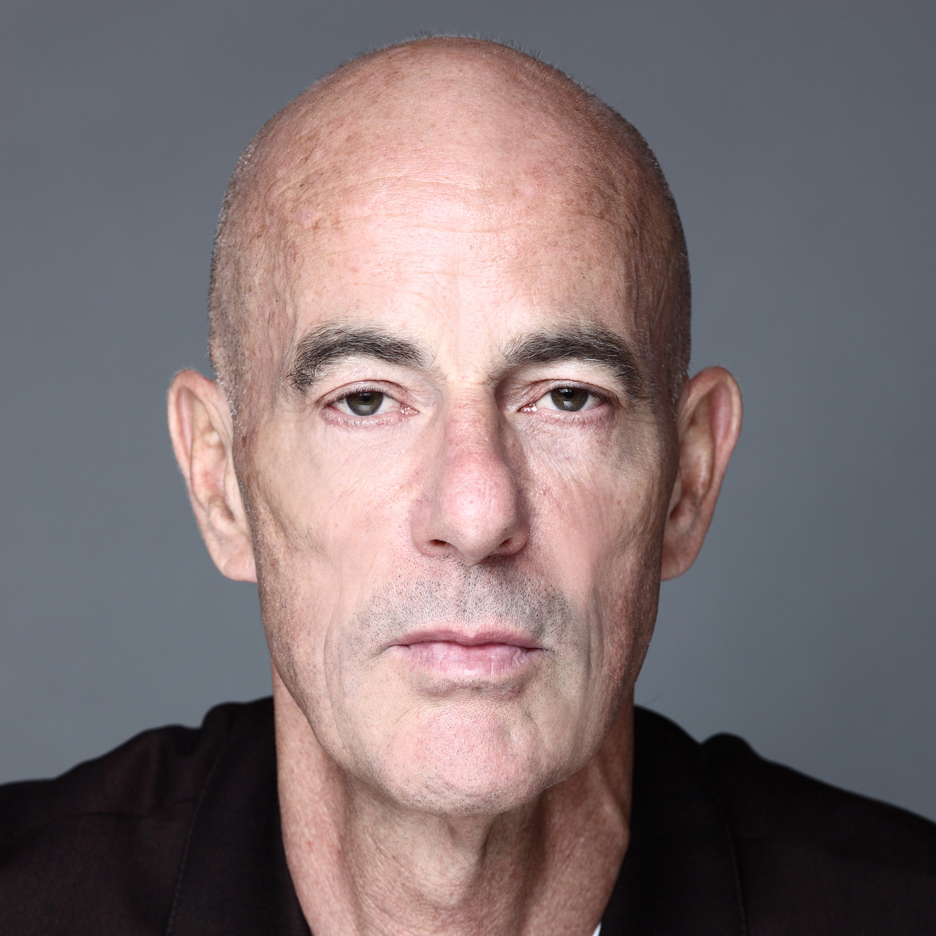

Architecture is a fundamentally humanitarian profession according to Swiss architect Jacques Herzog, who believes a building's success should be judged on whether it is filled with people.

"I hope that every architect has a humanitarian approach to architecture," Herzog told Dezeen. "I think architecture is about that, I really do."

"I would be sad and cynical if that wasn't the case," he added. "If architecture was just about form and pleasure it would be absurd."

The co-founder of Basel firm Herzog & de Meuron was speaking to Dezeen at a press tour of the studio's newly opened Blavatnik School of Government at the University of Oxford earlier this week.

"Oxford is an almost sacred territory for world class education," he said. "Its architectural heritage is equally impressive."

"We saw the Blavatnik School of Government as an opportunity to connect back to the traditional building typologies such as the interior courtyard and the stack of different volumes."

Herzog said that the design for the school was imbued with physical manifestations of the school's ethos of openness and transparency.

"They just wanted a nice building," said the architect. "Mostly [an education building is] for young people – people who are in their own making – so it's good to encourage everything that is about encountering, informal meeting, so there are friendships and connections which last longer than the time they spent in that building."

The building's spiralling concrete form features horseshoe-shaped elements based loosely on the layout of parliamentary buildings, and features glazed classrooms, offices and "Europe's largest double-glazed window".

Spaces are arranged around a curving atrium, intended to encourage students and tutors to join in impromptu discussions between floors.

"It is made to stimulate communication and informal exchange between students, scholars and visitors from all over the world," Herzog said.

While the firm primarily works on public buildings – it is currently undertaking revamping Chelsea FC's London stadium and working on a curvy tower block in New York – Herzog said variation is vital and likened the design process to exercising a muscle.

"I think being an architect and doing different things is like the muscles in your body, you have to train the different muscles – the small ones and the big ones – so that you remain flexible and active," said Herzog. "If you just do the same thing you become an expert and a specialist, and you become blind."

"Private homes is the one thing that we like least, but I think it's important that you try to go back to different types of commissions," he added.

The firm is set to participate in the Venice Architecture Biennale later this year. This year's edition will be directed by Chilean architect Alejandro Aravena, whose radical approach to social housing also made him the winner of this year's Pritzker Prize.

Despite this, Aravena claimed architects should never feel morally obliged to work on socially responsible projects when speaking at the Biennale press conference this week.

But Herzog said humanitarianism is inherent to architecture and warned against placing too much emphasis on Aravena's approach as the Biennale's creative director.

"I think we shouldn't overestimate the director who organises the Biennale, because I think it's more about the Biennale and the people and their projects," said Herzog.

"I don't know how his show will be," he continued. "I think it's good to have such different concepts every time, some are successful or less successful."

Irrespective of its director and its theme, Herzog said the Biennale will continue to be blighted by financial problems and take advantage of young architects so eager to exhibit they are willing to self fund their projects.

"There are always the same problems – not enough money," Herzog told Dezeen, "and the young architects are so proud to participate – that's why they are ready to pay, even if they lose a lot of money. But somehow it works."