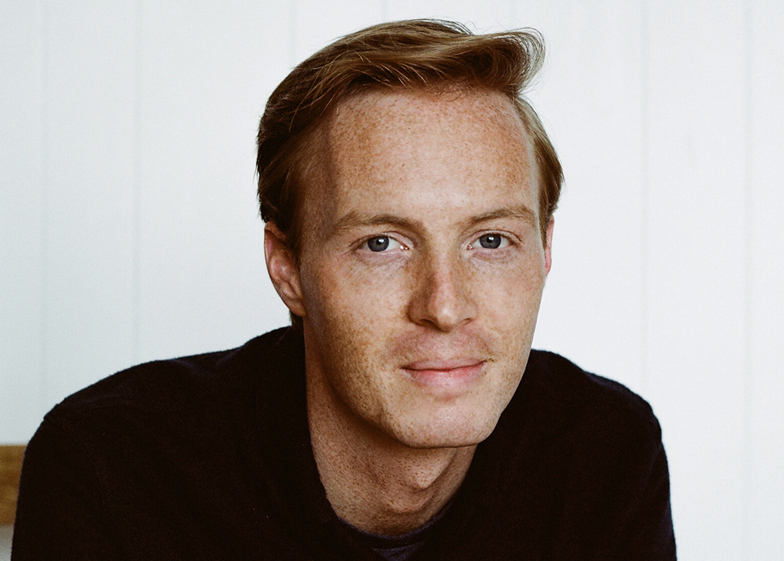

Interview: how did a tiny "slow lifestyle" magazine from Portland become one of the most influential forces in design? Dezeen's Dan Howarth spoke to Kinfolk co-founder Nathan Williams to find out.

Kinfolk has grown from a little-known independent publication to a household name in less than five years.

The Kinfolk look has become so influential that every over-styled, washed-out Instagram photo of a succulent or a cup of coffee is now deemed to be part of its visual bandwagon.

"If you go through the Kinfolk Instagram there's not a single photo of a latte," Williams told Dezeen, "but somehow it's started and kind of grown as its own thing that is actually completely out of our control."

In an interview with Dezeen last year, Fab co-founder Jason Goldberg described Kinfolk's earthy, analogue-style photography of rustic interiors and objects as "a little bit like Brooklyn, a little bit Shoreditch, hipster yet accessible".

"Everyone wants to have the Kinfolk look," Goldberg said. "People will seek out an object, and put it on their table, spend like an hour just getting ready for an Instagram photo, put a filter on it and they've got it, that's the Kinfolk look. It's fascinating that people do that."

Williams – the magazine's 29-year-old Canadian co-founder, editor-in-chief and creative director – originally set up the publication with friends in Portland, Oregon, while working as an analyst at financial corporation Goldman Sachs.

"When we first started working on the magazine the core focus was more on food, shared meals, the idea of gathering around a table and sharing ideas with likeminded individuals, that was very much the focus," he told Dezeen. "Our tagline was 'a guide for small gatherings' and it got a lot of traction right when we started it."

The first issue of Kinfolk was published in July 2011, around nine months after Instagram first launched. It was first published by Weldon Owen in San Francisco, then independently after the seventh issue.

"We worked with them for the first seven issues and learnt the ropes of magazine publishing: meeting with distributors, figuring out how to do the proofing and the printing process so that we could eventually break off and publish the magazine independently on our own," he said.

Kinfolk quickly expanded to cover all aspects of lifestyle and focussed on the idea of "slow living", with a young, aspirational creative audience in mind. Around 70 per cent of its readership works in the creative industries, according to Williams.

The quarterly magazine currently has a circulation of 80,000. Each issue features a minimal matte cover with a pastel-coloured background, and contains around 176 pages printed on 80# Accent Opaque stock.

Building on its success, Williams set up his own lifestyle publishing house Ouur Media, which produces bespoke campaigns, films and publications for clients including Zara, Toast, West Elm, Diesel and LG Electronics.

The company has also produced two books: The Kinfolk Table and The Kinfolk Home, and will launch a new interiors title this autumn.

While maintaining offices in the USA and Japan, Williams shifted the operation's headquarters to Copenhagen last year, where he also set up the Norm Architects-designed Ouur Gallery within the same building.

"As a city and as a culture here, it really overlaps with a lot of the values we have at the company and the publications we work on," he said.

Read an edited version of the transcript from our interview with Nathan Williams below:

Dan Howarth: How did Kinfolk get started and what were the initial ideas?

Nathan Williams: It originally was a project with myself and a few friends. When we first started working on the magazine the core focus was more on food, shared meals, the idea of gathering around a table and sharing ideas with likeminded individuals. That was very much the focus and our tagline was "a guide for small gatherings" and it got a lot of traction right when we started it.

But after a few issues we started doing surveys, talking to the readers and thinking about it more ourselves and we decided that the reason it was resonating with people wasn't so much because of the gathering, but just the general idea of quality of living – figuring out what matters most to you and then structuring your lifestyle around that to make sure you're making time for the things you care about.

So the issues after that we restructured the editorial scope, and shifted away from food and dinner tables, and really just started exploring that idea of quality of life. For us, we've focused on that idea of slow living.

Slow living not so much in the way of kicking back and hammocks with cocktails, but more taking the time to really think about what you want to be doing and what feels most beneficial, which is a fairly subjective way of thinking.

Dan Howarth: What was your business model at the beginning?

Nathan Williams: When we started the magazine, we launched it ourselves but partnered with a fairly established publisher in San Francisco, Weldon Owen, and they're owned by Bonnier AB corporation, a fairly large magazine publisher based out of Sweden.

So we worked with them for the first seven issues and learnt the ropes of magazine publishing: meeting with distributors, figuring out how to do the proofing and the printing process so that we could eventually break off and publish the magazine independently on our own. Which we did after the seventh issue and we've been doing ever since then.

Dan Howarth: You very quickly developed quite a niche aesthetic. Was that something that you pushed from the beginning?

Nathan Williams: It was definitely part of the initial planning. We wanted it to feel like a calm, slow, peaceful place for a reader to come, by flipping through the magazine it would evoke the same emotions that you have in the late evening hanging out with friends.

The way that we wanted to do that was to really keep it quite minimal, not just the layouts but also the colour scheme that we were using. A lot of the original typefaces were very straight forward. The idea was that it would just be uncomplicated and an easy reading experience.

I think a lot of that has carried through the issues over the last few years but the magazine has evolved and matured quite a bit. It does look quite different from the original issues. I think that's just part of us as a team growing up with our readers and wanting to try new things.

Dan Howarth: Are there any specific references that you use for the styling, such as Scandinavian design or Minimalism?

Nathan Williams: Not necessarily Minimalism but definitely a lot from Scandinavia and Japan. We have our editorial team there, and travel back and forth from Osaka a lot. Since we've been doing that for the last couple of years the Japanese influence has seeped into the magazine more.

Dan Howarth: How do you go about presenting interiors?

Nathan Williams: A lot of the interiors magazines that we subscribe to and that we have coming to our office are generally quite focused on the design and the styling, and often leave out the people and the life and the experiences that happen in the home.

As we were working on the books and as we work on each issue of the magazine, we really do push for a lifestyle angle, meaning who lives there, what do they do, why have they set up their home in this way, and why does that work and function for the way that they live.

I think that does make it much more interesting. We'll never shoot or feature a home without including a portrait of the home owner.

Dan Howarth: Have you noticed the magazine's influence on platforms like Instagram – the very curated images of table settings etc that look like they could have been taken from the pages out of the magazine?

Nathan Williams: That's definitely something that I have noticed. I wouldn't credit Kinfolk exclusively for that, I think that's somehow become quite a trend on Instagram and social media in general.

Frankly, I don't totally understand it. The [image of a] Kinfolk cover on a coffee table with a latte, we've got so much traction from that. It's been a great way for us to market the magazine and to gain a lot of exposure for it but it's never anything that we have solicited.

If you go through the Kinfolk Instagram there's not a single photo of a latte, but somehow it's started and kind of grown as its own thing that is actually completely out of our control. There's even hashtags that are believed to be from Kinfolk, like a "live authentic" hashtag and others that we've never used, created or associated ourselves with, but it's just a beast on its own. It can actually be kind of scary.

Dan Howarth: Are you happy that it has taken on a life of its own?

Nathan Williams: Yes and no. It's useful for the growth of the magazine and the visibility, but there's also a negative side where a lot of those photos that float around the internet can feel quite contrived.

A lot of them are meticulously styled for the purpose of sharing that moment, when really the core values of the magazine are about enjoying that moment and being with the people that you are with.

It's not about any type of facade or publicising the lifestyle that you have. It's all about much deeper values, much deeper experiences, really genuinely spending time with the people that you care about and in that way, it's not great. It actually can be a negative thing for us.

Dan Howarth: Do you think that may have caused people to have ideas about the magazine that aren't particularly what you intended originally?

Nathan Williams: Yes absolutely, there's things that we do as a team to try and counter that. In a recent issue, the Family issue, we did a feature about memories. The whole thing is about the act of taking photos and how we used to retain memories by telling stories. We would actually treasure those photographs and put them in an album and return to them years later, and it would bring back those memories.

That's changing a lot. [Now] it's really much more about sharing that moment instantaneously, not actually returning to it, not cherishing that memory later on.

So we are publishing stories about it, but then also things like the events that we do. We did a dinner series for a couple of years, over 300 dinners, but then eventually starting asking guests to not bring their phones, to leave them in their bags and we explicitly discouraged all guests before the meal from taking photos because it got to the point where a lot of people were buying tickets and coming just for the purpose of sharing that they were at a Kinfolk dinner which was completely against our objectives.

The point in doing it was to help readers actually to connect with people in their local community, meet other artists, hear what other people are doing. When we were at some of the events, how many phones were out and how many people were just distant was quite discouraging.

Dan Howarth: Do you find that a large portion of your readership comes from the creative community?

Nathan Williams: Yes they do. We have done a couple of surveys, and they usually come back with about 70 per cent of the readers working in some sort of creative profession. A lot of designers, editors, photographers, and lots of stylists.

Dan Howarth: Does that inform what you put into the magazine?

Nathan Williams: We do keep that in mind. It's fortunate that our actual readers are the target readership we have as well. The magazine is created with that target demographic in mind. It's made for 25 to 35-year-old creative professionals.

So the people we choose to feature in the magazines and the stories we created, are created with them in mind. We're trying to find things that are interesting for them.

Dan Howarth: Why did you decide to move to Copenhagen?

Nathan Williams: We have been planning to open a second international office for a while. We went through a roster of other cities we were considering, and really myself and a lot of the team just really like Copenhagen.

Also as a city and as a culture here, it really overlaps with a lot of the values we have at the company and the publications we work on. If we as a team are trying to the study the idea of quality of living, it's really a fantastic place to set up a lab for researching it here.

As a city and the people, it has a really good grasp on work-life balance and sorting out priorities and that fits with the magazine. We also have a really strong network of contributors here. Even when we were in the US, almost three-quarters of our productions were done between London, Copenhagen and Stockholm, so it's extremely helpful for us to have a team over here to be on set and to be working directly with our contributors.