Opinion: temporary architecture is having a "moment" in Europe, and it has some serious lessons to offer architects that are still obsessed with permanence, says Aaron Betsky.

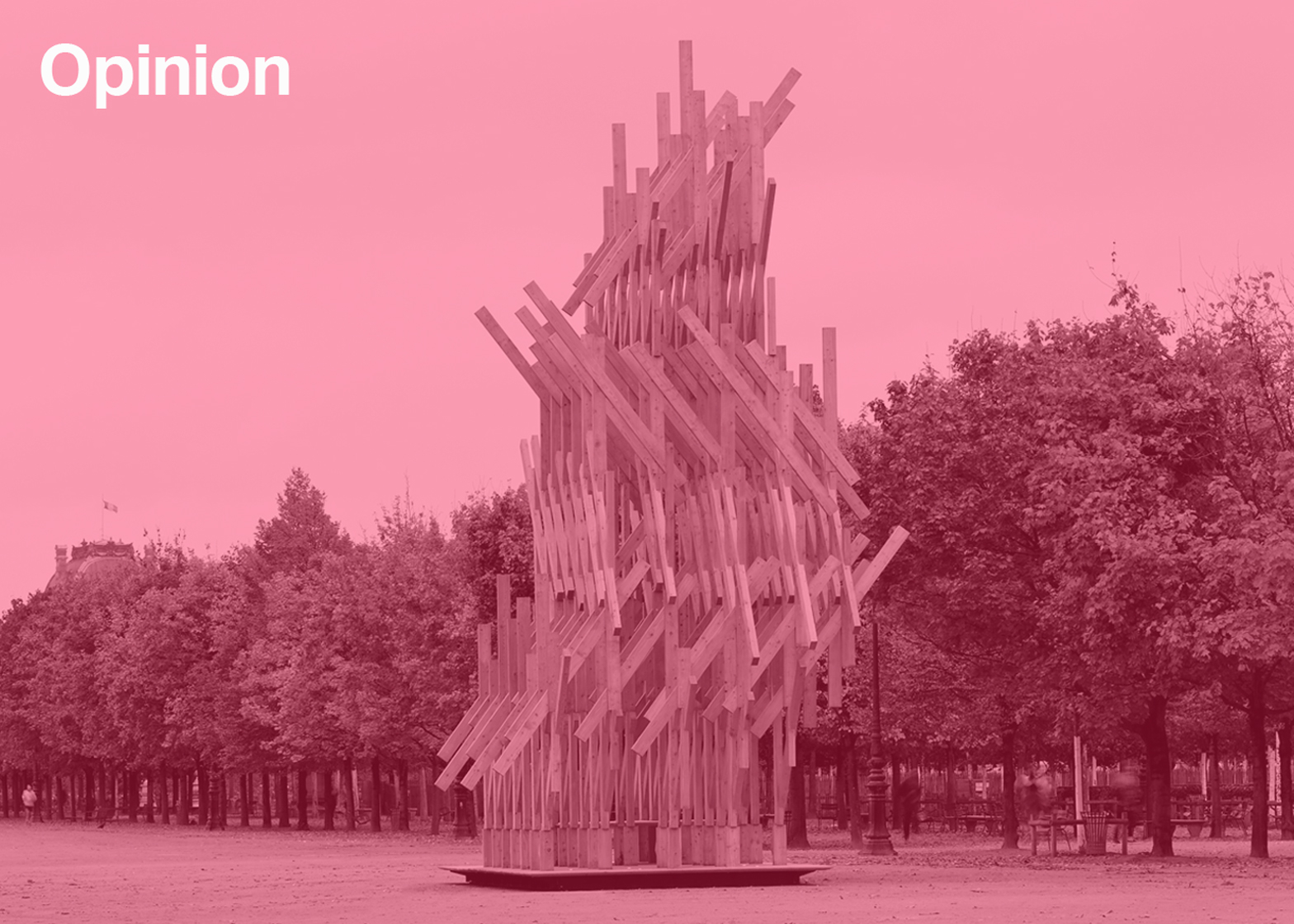

Architecture is going pop. It is finally sloughing off its ridiculous obsession with eternity, and learning to live in and for the moment. Pop-up architecture, temporary structures, and other ephemeral frameworks for equally evanescent events have become all the rage, especially in Europe.

They have increasingly gained worldwide attention with recurring events such as the Serpentine Pavilion and MoMA's summer installations at PS 1, while the award of the Tate Prize to the masters of low-cost, fast, socially active architecture, Assemble, reaffirms the serious intent of such forms. A new book by Cate St Hill, published by the RIBA, This Is Temporary: How Transient Projects Are Redefining Architecture, celebrates such event structures.

What I love about this new wave of temporary architecture is that it combines the fun with the serious, and puts the social back into socially conscious architecture.

That is not to say it is either all fun-and-games play structures or socially important parklets and neighbourhood housing we are talking about. The vernacular bulk of temporary architecture is commercial and residential, and it suffers from some of the same problems that make it so difficult to do something good in these fields when the structures are meant to last.

It is hard to find refugee housing that is more than utilitarian, and you will be lucky to locate even working camps. We stuff those without permanent homes into tents, containers, or school gyms, with few enough amenities, let alone moments of joy and beauty, so that they will not feel at home there.

At the other end of the spectrum, the whole point of pop-up retail is to invest as little as possible, sell everything, and then leave. Anything more than a container with its side doors open is a lot. When the pop-up has too much pizzazz, like the now proliferating Dover Street Markets, they become permanent.

The fun and games are in the cultural and sports worlds that have been the traditional playground for architects who must be so sober in other fields, but also in the area of social activism or tactical urbanism, where architects have found a way to disentangle this fast form making from old-style social planning in favour of direct, bottom-up action.

In St Hill's book, Assemble and Practice from the UK, as well as EXYZT from France, exemplify the latter, with Studio Weave and Morag Myerscough at the other extreme. In the larger world, it is the spectrum that runs from the various Serpentine Pavilions to the work of tactical urbanists such as Urban Think Tank.

The real fun stuff is the basketball fields Nike lays down in parking lots or their soccer fields on container ships. I am sorry to say they tend to make do without architects, although years ago MVRDV transformed the square in front of the Richard Meier-designed MACBA in Barcelona in exactly that manner.

In reality, the distinctions between careening constructions and critical constructs are not that clear. Almost all the joyous makers of colorful pavilions see their work as neighbourhood activators and social commentary, while even the most serious activists clad their building in populist hues and forms.

The point for all of them is for architecture to dissolve into our popular culture as quickly as possible, leaving behind changed perceptions of place, a new sense of community (many of these structures are venues for performance or discussion), and a sense that you can make a place your own, together, if even for a moment.

They show us that we do not have to live in the bland and blank grids that unseen powers have decreed for us. We can wrest them away, make them alive, and make them our own – as long as we don't leave them out long enough for codes to be applied, ownership to be disputed, branding to be applied, or just wear and tear, familiarity, and boredom to set in.

This kind of pop-up architecture thus has a clear and limited function in our society, but I also think it has a larger message for the discipline in general. We have all been brought up with the idea that the best architecture should be timeless. It should rise beyond the vagaries of current fashion and style. It should embody values that are permanent. It should accept, but not be defined by, the rhythms of everyday life. It should last for as long as possible and then make a good ruin. Architecture, in other words, should be monumental, abstract, and difficult and expensive to build.

Modernism ate into that conceit, only to find itself being criticised for being not well-built and flighty. Postmodernism took that as a compliment, but gave us facsimiles of time- and place-bound structures.

Time after time architects have said that architecture should only last as long as a society's commitment to it (Louis Kahn), have proposed Fun Palaces, pointed out that architecture under construction is much better than when it is finished (Frank Gehry), or written books about Event Architecture (Bernard Tschumi), but in the end they have always made heroic feats of concrete and steel construction.

What makes this result even more absurd is that every building has to be adapted to changing uses, often even during construction. Embedding massive amounts of material in durable structures is not a very sane environmental strategy either; rather, we should be figuring out how to invest as little material as we can in any given structure, and then make sure that it can be reused as efficiently as possible. German law even makes that part of the evaluation of a building's environmental performance.

Beyond such issues of function, style, and ecology, lies the notion that, by making buildings as expensive monuments, we guarantee that only the social, political, and economic elite can pay for them, and that they thus embody their values and priorities.

Architects who see themselves as building for the ages are only mirroring the desire of the clients to leave a legacy – and we all know how well that worked out for Albert Speer, Harrison and Abromowitz working for Nelson Rockefeller in Albany, or anybody employed by Donald Trump. Moreover places change, so that the context of a building is also often already different they day it opens then when it was first designed.

On a philosophical level, the notion that we can fix time and place through human action is something that the intensity and reach of technological inventions, themselves no more than the embodiment of humans re-crafting their reality, have long since gainsaid. The question now is more whether we can go with the flow, understand that we have made a complete (ir)reality in time and place, and can learn how to build within that world in a manner that creates a constantly changing relation between ourselves, other humans, and that consensual hallucination we have made.

So let's hear it for temporary architecture. Let's rejoice in what is here today and gone tomorrow (provided it is properly reused, and many of the projects St Hill shows are themselves made out of recycled materials), and let's work to make our world better bit by bit and moment by moment.

Finally, let's enjoy the fact that temporary architecture is letting loose a wave of creativity, inventiveness and serious effectiveness that the discipline has not seen in ages.

Aaron Betsky is dean of the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture. A critic of art, architecture, and design, Betsky is the author of over a dozen books on those subjects, including a forthcoming survey of Modernism in architecture and design. He writes a twice-weekly blog for architectmagazine.com, Beyond Buildings.

Trained as an architect and in the humanities at Yale University, Betsky was previously director of the Cincinnati Art Museum (2006-2014) and the Netherlands Architecture Institute (2001-2006), and Curator of Architecture and Design at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art(1995-2001). In 2008, he also directed the 11th Venice International Biennale of Architecture.