Technologies like driverless cars and smart heating systems could end up making cities dysfunctional according to Maarten Hajer, chief curator of the International Architecture Biennale Rotterdam 2016 (+ interview).

Speaking at an opening event for the biennale, Hajer called for architects and designers to stop treating the advent of smart technologies as inevitable, and to question whether they will solve any problems at all.

"People with lots of media force pretend to know exactly what the future will look like, as if there is no choice," he said. "I'm of course thinking about self-driving vehicles inevitably coming our way."

Discussions about the future of cities are at risk of being "mesmerised" by technology, he added.

"We think about big data coming towards us, 3D printing demoting us, or the implication of robots in the sphere of health, as if they are inevitabilities. My call is for us to think about what we want from those technological advances."

An expert in public science and urban planning, Hajer is professor of Urban Futures at Utrecht University. For the seventh edition of the biennale, known as IABR, he has chosen the theme The Next Economy.

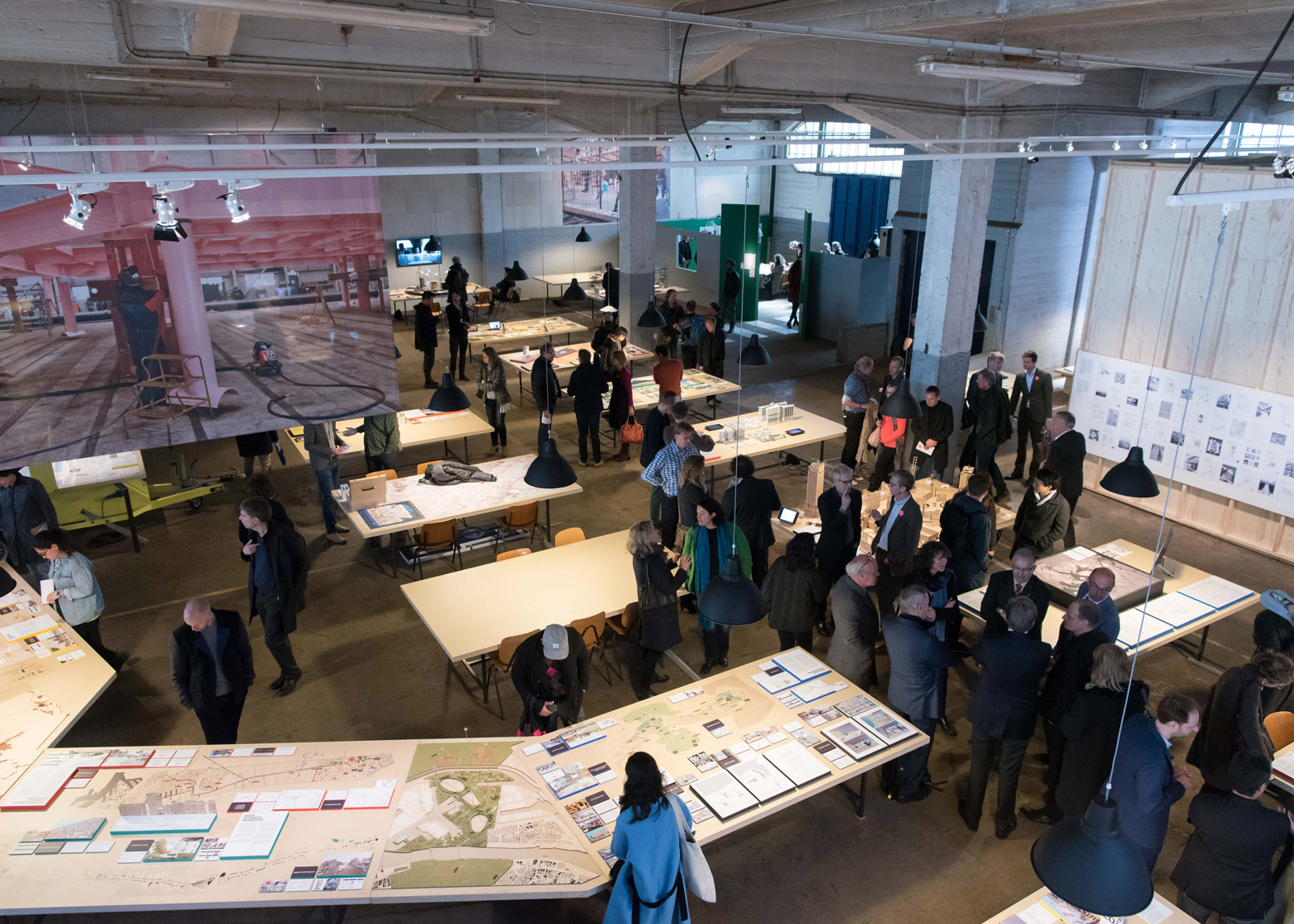

This exhibition, which takes place in a former coffee warehouse in Katendrecht, brings together over 50 projects that offer a rethink of existing city systems, ranging from mobile vegetable shops in China to a huge housing cooperative in Belgium.

According to Hajer, "low-tech" projects like these offer opportunities for cities to function more efficiently, while smart technologies, by contrast, often provide the answer to a problem that doesn't exist.

"I have nothing against good technology, it's wonderful, but you always want social problems to be the priority," he told Dezeen in an interview.

"If it doesn't help us get CO2 down, if it doesn't help us make cities more socially inclusive, if it doesn't help us make meaningful work, I'm not interested in smart technology. Sometimes I think: "if smart technology is the solution, then what was the problem again?" It's almost like a solution looking for a problem."

The term smart technology is generally applied to any digital device capable of making decisions without human intervention, in response to its environment.

Hajer claims the main issue is the systematic way these devices operate. He suggests that many create an entirely new set of issues, particularly regarding privacy – a topic that Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas drew attention to during the 2014 Venice Architecture Biennale.

"Just think about the data requirements of a self-driving vehicle, the sending back and forth of data. You need a stunning number of data centres," explained Hajer.

"You also create reliance on GPS, which is a monopolistic military technology. So there are lots of systemic risks involved that are not getting the attention that they need."

The IABR opened to the public earlier this week at Fenixloods II, and will remain in place until 10 July 2016.

Read an edited transcript from our exclusive interview with Maarten Hajer:

Amy Frearson: In your introduction you said we don't need smart cities, we need smart urbanism. Can you explain the difference?

Maarten Hajer: A smart city is a lot about people believing in city technology and its application to urban problems. It's a lot about big data that makes us understand the world better, so we can make it more efficient. But urbanism is a much longer tradition looking at what makes cities work. It's a much more humanities-based and philosophical tradition.

I think there's a big etymological clash between the science of the smart city and the more social science of urbanism.

Amy Frearson: Does technology play a role in smart urbanism?

Maarten Hajer: Absolutely. I have nothing against good technology, it's wonderful, but you always want social problems to be the priority. If it doesn't help us get CO2 down, if it doesn't help us make cities more socially inclusive, if it doesn't help us make meaningful work, I'm not interested in smart technology. Sometimes I think: "if smart technology is the solution, then what was the problem again?" It's almost like a solution looking for a problem.

Amy Frearson: Are there any particular technologies that you think could have potentially disastrous effects on our cities?

Maarten Hajer: I think the systematicness of smart technology is a big problem. It's not a particular technology per se, but how it is going to be employed.

Today I read a newspaper report on the fact that insurance companies are saying: "I need that big data because then I can really calculate the risks of particular behaviours." But it would be an encroachment on privacy in an incredible way.

Amy Frearson: Do you think driverless cars will be good or bad news for cities?

Maarten Hajer: The question is, what is the point about a driverless car? I don't have a problem with driving my car. But if a driverless vehicle can help us reduce the number of cars in a city, if it can help us make the quality of the public domain better, I might be interested. The car industry obviously has an interest in selling those cars as a commodity, so that you first get a car without a steering wheel so-to-say, and then bit by bit you get to something else.

I think it might actually be a way to organise a new, intermediate transport between what we now call public transport and private transport. But then I think governments have to steer towards that particular goal and say very clearly that, for example, in 2025 we want to have 50 per cent less vehicles in the cities or something, which is a possibility. Then I think self-driving technology would get another application.

Amy Frearson: Is there a possibility that self-driving cars could have catastrophic effects on cities?

Maarten Hajer: There are colleagues of mine who argue this. I have an environmental background so I know the data requirements of self-driving vehicles also makes for a very big energy bill. Just think about the data requirements of a self-driving vehicle, the sending back and forth of data. You need a stunning number of data centres. You also create reliance on GPS, which is a monopolistic military technology. So there are lots of systemic risks involved that are not getting the attention that they need.

If it was an open system I would be much more comfortable, but that's not the way it usually goes.

Amy Frearson: Do you think enough architects and designers are addressing these kinds of issues?

Maarten Hajer: It's not a coincidence, I think, that lots of the stuff that is on show here [at the biennale] is not purely design, it is designers working in collaboration with others. The design practice as a small discipline, I think, is not that interesting at the moment. What's the point of a supermall that leans backwards or something? That's trivial architecture. But if you could redesign a neighbourhood so that it can cater to local people with local food and healthy food and you have a design approach to that, you can make a hell of a difference.

Amy Frearson: Do you think we can say anything for certain about the future of our cities?

Maarten Hajer: I think that, although you have moments where cities are on the up or declining, the vitality of cities is just a remarkable thing. It's our single most impressive cultural achievement, the city. It's Mesopotamia. That's where we got out of the basic agricultural practices, that's where we created markets, that's where learning started, that's where the alphabet was made, that's urban.

The locus of the city is the locus of innovation and invention, that is something that cannot be killed, not even by smart city technology.

Amy Frearson: Some people think the idea of smart city is a cause of cities losing their regional identities. Will practising smart urbanism help cities to hold on to their regional identities, or does it actually matter at all?

Maarten Hajer: One thing that I would focus on during these three months [of the biennale] is that all local initiatives find each other to learn from each other. We have several big events, there are people from very different cities; Rio de Janeiro, Cape Town, Beijing but also European cities, coming together and comparing notes about how can we learn from each other. While they all do regional things, they're still informed by global exchange, I think that is very valuable.

In Beijing, designers are pushed out because it's expensive and they rediscover the periphery, they develop new ways of living together. While now everybody says the effects of agglomeration means everyone is always getting closer and closer together, I'm not so sure it will ultimately only go in that direction. I think that it is more dialectical.

If London becomes uninhabitable because the infrastructure cannot cope with the increasing numbers, then we may have a moment that the outsides pick up.

Amy Frearson: In your introduction you said there are many situations where low-tech solutions are more efficient answers to city problems than smart technologies. Can you give me some examples?

Maarten Hajer: There are some remarkable African examples. Of course there they really laugh when we say "maker movement" because they have constantly been making, they really laugh when we say "recycling" because they have always been recycling, because they are so poor.

There is this wonderful place called Suame Magazine, an area in Ghana, which is where all the cars from Europe ultimately go. They are disentangled, nuts and bolts, everything, and put back together; new cars are made of old stuff. That's a stunning African story, it's really low-tech but it works.

There is also an energy heating system. Solar PVs are good for the electricity but most of your costs as a household go to heating. What this system shows is that there is residual heat from industry, and if you saved that to be used for households – it's difficult to get it economically viable – but if you use it in combination with geothermal then it is a fantastic business. Geothermal is not completely low-tech but it is much more feasible.

Amy Frearson: What about sustainable technologies? Do these solve a problem in cities?

Maarten Hajer: I'm deeply convinced that if people produce their own energy it makes them very aware of how much energy they need. In that sense it is crucial. Of course any energy that you make yourself is wonderful. In particular, if it allows you to share it with neighbours in a smart grid, it makes you far less dependant on the outside. That is actually wonderful.

For instance, I have nine solar panels on my roof, and that covers about one third of my electricity consumption. I can't put more on my roof, it's too small, and many people don't have as big a roof as I have. So there is a big discrepancy between what you can achieve through the centralised system. But in terms of awareness, these decentralised systems are really crucial.

Also for instance, we always have a discussion in waste on whether with plastics, if you recycle them yourself – if you have to collect them and bring them to a bottle bank for plastics – it makes you aware that more than half of your waste is plastic. In that sense, keeping things close to consumers is not trivial, it's really important.

Amy Frearson: Do you think exhibitions and events like this biennale can have any real impact on awareness?

Maarten Hajer: I do obviously hope so. I'm not naive and think the world will suddenly will pick up speed in a good direction. I do believe that we are experiencing a crisis of the imagination; that we see risks and people are almost apathetic about what we can really do. I think that we could make this into a really crucial moment for designers providing new imaginaries that can be beacons for people to steer towards. In that sense it's really a call to designers to pick up that challenge.