OMA and Allies and Morrison have completed the redevelopment of the former Commonwealth Institute in London, adding three blocks of private housing that have helped fund the transformation of the protected building into a new home for the Design Museum (+ slideshow).

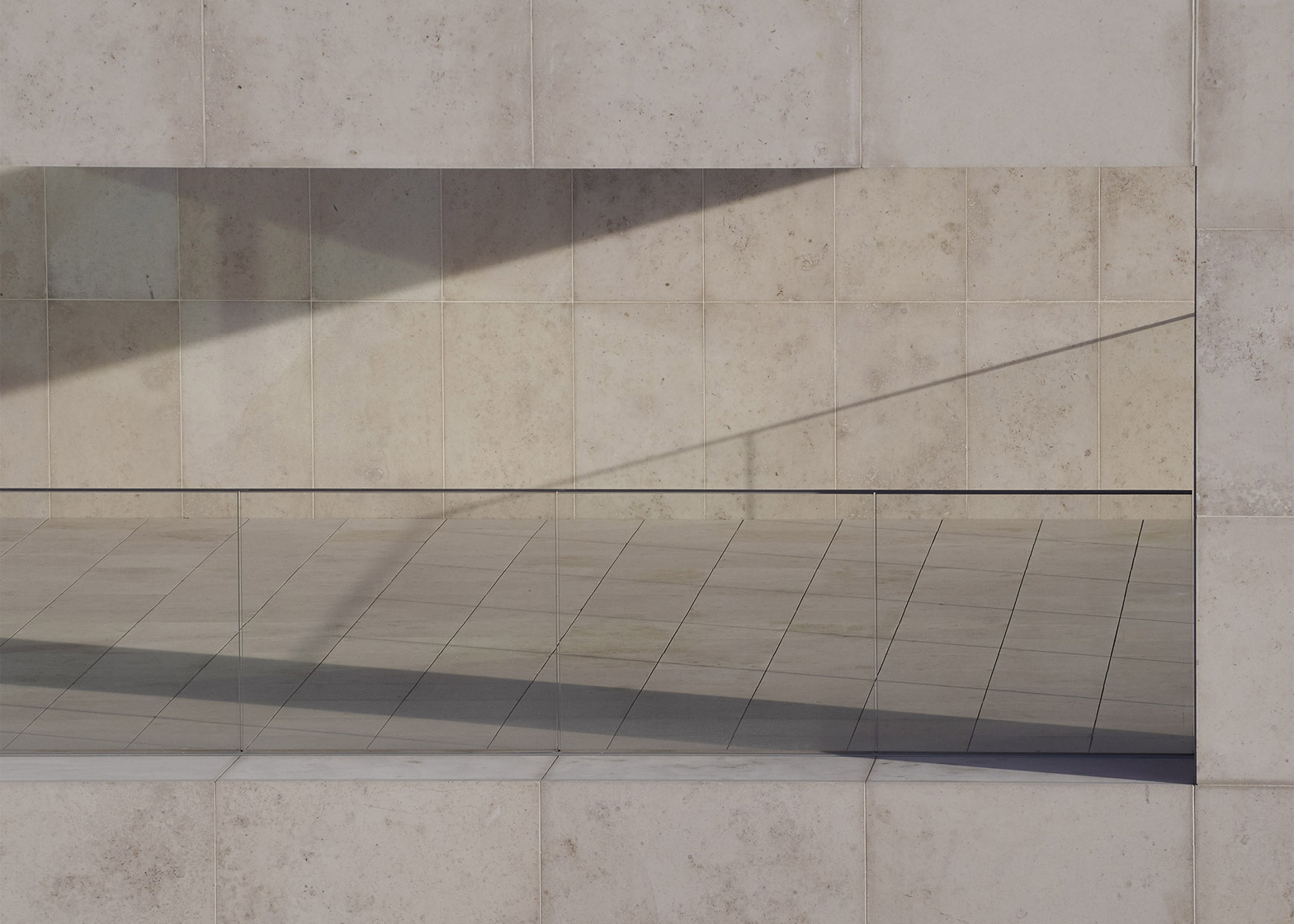

Dutch architecture studio OMA partnered with London firm Allies and Morrison to create three limestone-clad apartment blocks called Holland Green around the Grade II*-listed former Commonwealth Institute in Holland Park, Kensington.

Sales of the 56 one- to five-bedroom flats within the development have helped fund the conversion of the 1960s building into a new home for London's Design Museum. Due to reopen in November, the building will feature an interior designed by John Pawson.

"This is the only project I know where in a way the booming property market has done something for the greater good of London," said OMA partner Reinier de Graaf, who led the design team.

"Something good has come out of it rather than just real-estate profits," he told Dezeen. "That was the idea and also I'm sure the reason why the local council granted this whole thing permission."

Each of the three cube-like housing blocks shares a similar design, but varies in scale from seven to nine storeys.

The smallest block faces Holland Park to the rear of the site, while the mid-size one faces Kensington High Street at the front to mitigate the impact of the largest building in-between.

"The [original] building is at 45 degrees from the angle of the predominant direction of the buildings there, so there are funny triangular sites around it," said de Graaf, whose other projects include the headquarters for fashion brand G-Star RAW in Amsterdam and the mixed-use pixellated Timmerhuis development in Rotterdam's city centre.

"We filled each one with a residential building – identical in form but different in proportion, like Russian dolls – so that the size of each cube responds to the immediate context," he explained.

Vertical rectangular cut-outs form full-height windows between each floor, while larger horizontal cut-outs and protrusions create single and double-height balconies, entrance areas and other outdoor spaces.

"They emphasise the preserved building because they offer a contrast," said de Graaf. "The repetitive facades are like graph paper, which essentially registers and emphasises the curve of the roof."

A basement level provides car parking, with private access to the apartment blocks and service access to the Design Museum's building, as well as shared facilities for residents including a cinema, swimming pool, spa and gym.

To help create the space for three housing blocks, the team demolished a rectangular office wing of the original 1962 structure by RMJM – one of the UK's influential mid-20th-century architecture firms.

Developer Stuart Lipton brought in Roger Cunliffe, an architect who had been part of the original team at RMJM in the 1960s, to consult on the project.

"Nobody knows the compromises in the original design better than the original architect," said de Graaf. "The original intention was 'a tent in the park'. So we decided to demolish the service wing, which the original architect was never very happy with – they referred to it as 'the train crash' internally in the office."

The existing diamond-shaped exhibition hall is known as The Tent due to its unusually shaped roof, which rises into multiple peaks supported by struts that reach the ground at an angle from each corner.

OMA and Allies and Morrison gutted the three-storey building, adding a more efficient glazed facade that echoes the original aluminium-framed blue-glass panels above the brick plinths around the base. New supporting structures were also added to accommodate the weight of heavy exhibition objects.

Its distinctive sheet-copper roof, which has a shape known as a hyperbolic paraboloid, has been refurbished.

"We decided, more or less, to operate from the gut and take certain liberties," said de Graaf. "The main thing really in need of preservation was the exhibition hall itself because of its very specific roof – the hyperbolic paraboloid roof, which was a special feature of its time."

"The best way to restore an old building is to give it a new use, that's the most sustainable form of preservation there is," he added. "We redesigned the core and shell, designed new facades – we essentially designed a new building."

OMA initially won the project in a competition in 2008 in partnership with London-based Allies and Morrison. The two also worked together on OMA's Rothschild Bank headquarters in the City of London, which was shortlisted for the Stirling Prize in 2012.

"The [housing] development was part of the brief because the cost to refurbish the whole thing properly – not just restore it as a monument but to refurbish it properly for a new user – was significant, and therefore money had to be made on the side to fund those costs," said de Graaf.

According to OMA, the total cost of the project was £120 million. The refurbishment of the exhibition hall came in at around £35 million, with Pawson's interiors adding an extra £20 million.

The original building had housed a cultural institution that focused on educating visitors about the various countries that formed part of the British Commonwealth through exhibitions and events. This closed in 2002, and the building struggled to find a new occupant.

In 2006 the British government controversially attempted to delist the building so it could be demolished entirely. In 2008 the Design Museum, on the hunt for a larger premises to allow it to display its permanent collections and bigger exhibitions, chose the building as its preferred site. It was granted the property rent-free for 375 years, and announced Pawson as the fit-out designer in 2012.

Its current home in Shad Thames, south London, will house the archive of architect Zaha Hadid, who died unexpectedly aged 65 in March 2016.

Like Dezeen on Facebook for the latest architecture, interior and design news »

Project credits:

OMA

Partner in Charge: Reinier de Graaf

Project Director: Carol Patterson

Project Managers: Mario Rodriguez, Isabel Silva, Fenna Wagenaar, Mitesh Dixit, Richard Hollington III, Beth Hughes

Allies and Morrison

Partners: Simon Fraser, Robert Maxwell

Director: Neil Shaughnessy

Associate Directors: Joel Davenport, Heidi Shah

Associates: Sean Joyce, Johanna Coste-Buscayret

Team: Dinka Beglerbegovic, Fabiana Paluszny, Stuart Thomson

Structural Engineer: Arup Structures

Services Engineer: Arup Services

Acoustics: Arup Acoustic

Facades: Arup Facades / FMDC

Fire: Arup Fire

Quantity Surveyor: AECOM

Landscape Architect: West 8

Interior Design: CZL

Lighting Design: RALC